Injured Illinois workers take 50 percent more time off than peers in surrounding states

Illinois law gives financial incentives to many injured workers to stay off the job and to doctors to prescribe more medications to workers’ compensation patients.

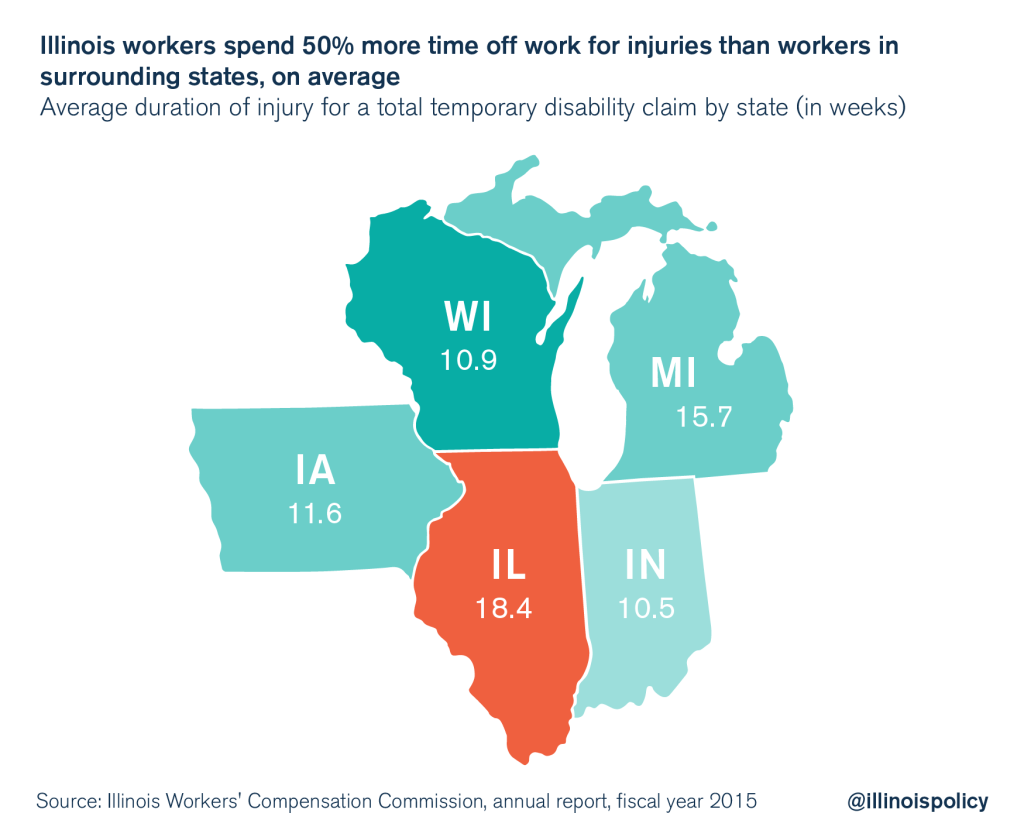

The Illinois Workers’ Compensation Commission’s 2015 annual report reveals that injured workers in Illinois spend an average of 50 percent more time off work than their counterparts in Indiana, Wisconsin, Michigan or Iowa. The report points out that total temporary disability claims in Illinois are for longer periods of time than those in most states covered in the study. The average time off work for a temporary injury is 18.4 weeks in Illinois, compared with 15.7 weeks in Michigan, 11.6 weeks in Iowa, 10.9 weeks in Wisconsin, and 10.5 weeks in Indiana.

This deserves attention not only because unnecessary time off work is a major cost driver for businesses and governments, but also because the long-term health of both workers and businesses is at stake. A look at two aspects of Illinois’ workers’ compensation system reveals how bad policies keep workers off the job longer in Illinois.

Illinois law gives some workers an effective pay hike when they are on workers’ compensation

Some workers in Illinois receive more take-home pay when they are injured than when they are working. Under workers’ compensation in most states, an injured worker usually receives two-thirds of his lost wages as a wage-replacement benefit. These benefits are untaxed at both the state and federal levels, so a worker who makes $3,000 per month before taxes will receive a workers’ compensation benefit of $2,000 per month, but will owe no federal or state taxes on that benefit.

What’s unusual in Illinois is that certain groups of workers receive 100 percent of their lost wages as a workers’ compensation benefit even though that income is untaxed. This creates an effective pay increase for some on workers’ compensation.

For example, the 2005 legislation signed by former Gov. Rod Blagojevich created an after-tax pay bump for lower-wage workers by raising the minimum wage-replacement rate. A worker earning no more than $220-$330 per week (depending on the number of dependents) gets all of his lost wages replaced untaxed, even if he is only a part-time worker. This creates a financial incentive for lower-wage earners to remain on workers’ compensation because they get more take-home pay and aren’t required to work.

In addition, Illinois’ Public Employee Disability Act provides that police and firefighters receive their full salaries for up to one year when they are injured. This full salary is also untaxed, meaning police and firefighters receive an effective pay bump for being injured.

This is not to say that policy should be drastically changed to put low-wage workers and public safety workers under duress when they are injured. Rather, they should simply be treated more like other injured workers. Even researchers from the Social Security Administration point out “the effect of a minimum benefit can be to ‘overcompensate’ low-wage workers in some cases.” When there is a greater financial benefit to staying home than there is to going to work, injuries in Illinois will result in more time away from the job.

Physician dispensing results in more time off work in Illinois

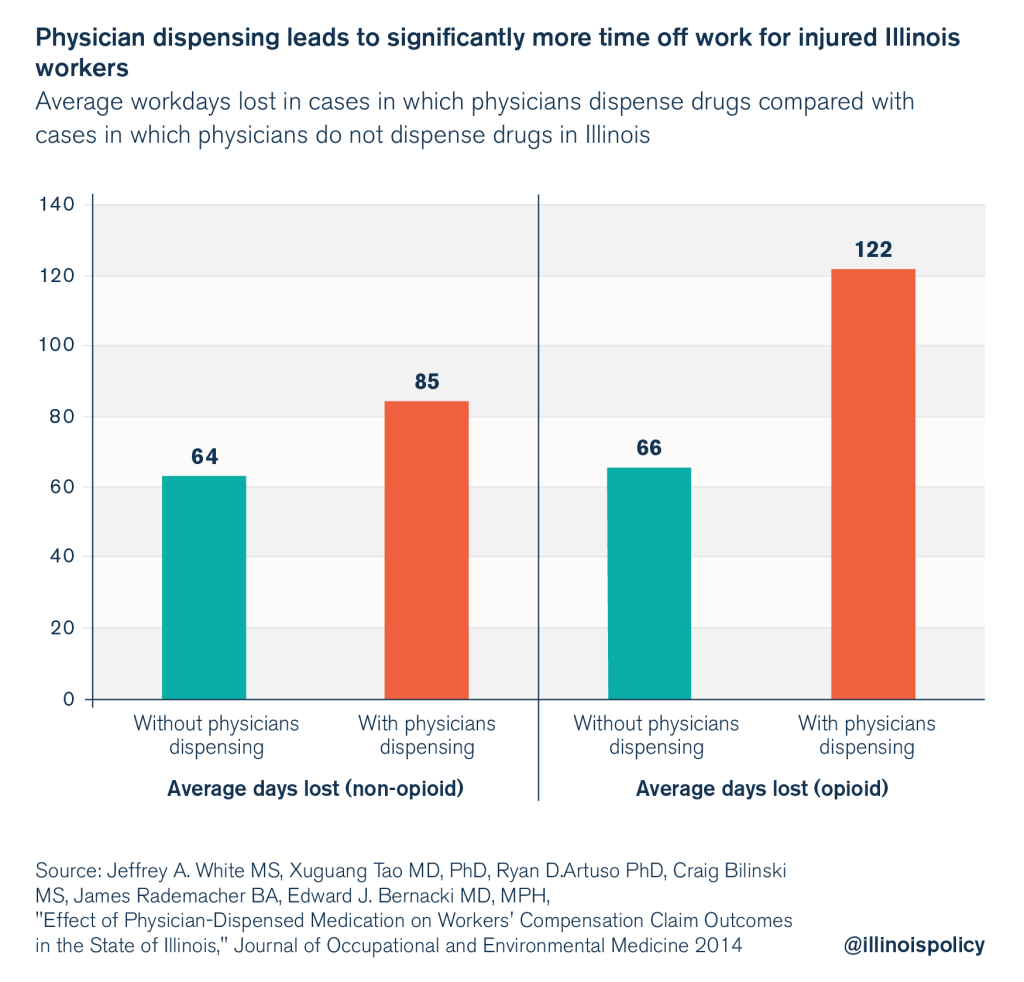

Another way state law causes injured workers to take more time off work is by allowing physicians to profit by dispensing drugs directly to their patients. Research by Johns Hopkins University medical scholars has shown that when doctors have a financial incentive to prescribe more medications – such as by selling the drugs they prescribe directly to patients – workers end up receiving more drugs and spending more time off work. Illinois doctors prescribe 3.2 times more medication when they sell those drugs directly to workers’ compensation patients than when a pharmacist sells the drugs prescribed. In such cases, workers spend 33 percent more time off work when the prescription is for non-opioid pharmaceuticals, and 85 percent more time off work when the prescription is for opioid painkillers.

Other states have previously dealt with this problem. When Florida banned physician dispensing of strong opioids in 2011, doctors became much less likely to prescribe them. In fact, the frequency of opioid prescriptions fell by 87 percent after the Florida law eliminated the profit motive inherent in physician dispensing. Texas and Indiana have enacted similar restrictions, with Texas outright banning physician dispensing except in rural areas with few pharmacists, and Indiana limiting physician dispensing to the first eight days after an injury.

Illinois’ comparatively longer time off work for workplace injuries needs to be studied further, as there are likely more causes then the two described here. Unnecessary time off is bad for both workers and employers, and the harmful incentives in the law hurt Illinoisans. Workers’ skills can diminish when time off drags on, which hurts workers’ long-term prospects. And when doctors dispense the drugs they prescribe, workers tend to receive more drugs, and more potentially addictive drugs, than they would otherwise. It’s also a bad deal for employers because businesses and taxpayers have to cover the cost of poorly crafted public policy.