Illinois Supreme Court defends inflated pensions for Chicago union leaders

Once again proving why the state must amend the Illinois Constitution’s pension clause, the court unanimously ruled in favor of a special perk that inflated union leader pensions to nearly three times the pension of the average worker.

The Illinois Supreme Court unanimously ruled Nov. 29 that the state constitution’s pension clause protects a perk granting inflated post-retirement pay – one that only benefits government employees who work for their unions.

The decision declares untouchable a pension-spiking provision available only to a select few workers, and underscores the need for a constitutional amendment and comprehensive pension reform in Illinois. According to one estimate, those inflated pensions will cost taxpayers more than $50 million.

In the decision – Carmichael v. Laborers’ & Retirement Board Employees’ Annuity & Benefit Fund of Chicago – the court held the Illinois General Assembly could not rescind a pension- spiking perk for employees of the city of Chicago and Chicago Board of Education who take time away from their government jobs to work for their unions.

Pension benefits are typically calculated as a percentage of a retiree’s government salary near the end of employment, with a higher percentage of salary granted based on years of service. But for certain retired Chicago union leaders, their pensions will instead be based on their union salaries, which were higher than what they earned in their positions with their government employers. As a result, their pensions will be nearly three times higher than the typical retired city worker, according to a 2011 report from the Chicago Tribune.

The Tribune estimated the cost of 23 such pensions at $56 million.

Since the city of Chicago and the Chicago Board of Education are not responsible for setting union salaries, the resulting higher pension costs were ultimately unpredictable for public officials and taxpayers alike. The General Assembly effectively outsourced responsibility for setting public pension benefits to a nongovernmental third party: unions.

The union pension-spiking perk was originally granted by the General Assembly in 1991, with no public debate and no cost estimates available, according to the Tribune. The court notes in the opinion that the General Assembly attempted to walk back this perk with Public Act 97-651 after receiving negative press coverage.

In other words, the General Assembly was caught red-handed doling out unaffordable benefits to select special interests. Yet when lawmakers tried to correct the mistake, the Illinois Supreme Court said no.

Although this type of abuse is not the sole cause of the Chicago pension systems’ poor financial condition, it is a perfect example of politicians doling out special favors and sticking taxpayers with the bill.

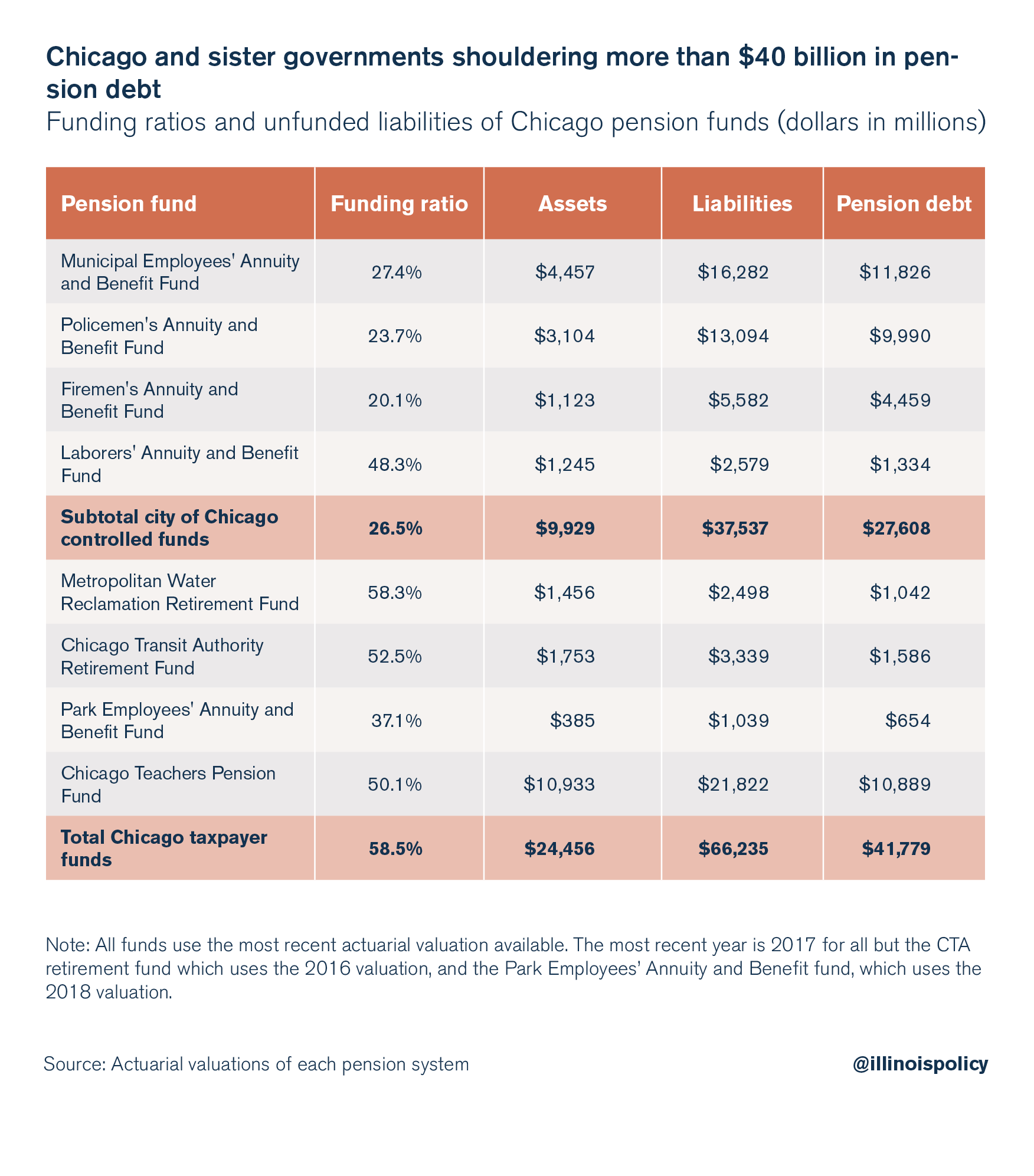

In total, the Chicago-related pension funds have more than $41 billion in pension debt.

Moody’s Investors Service currently gives the city a junk credit rating, largely due to unfunded pension liabilities.

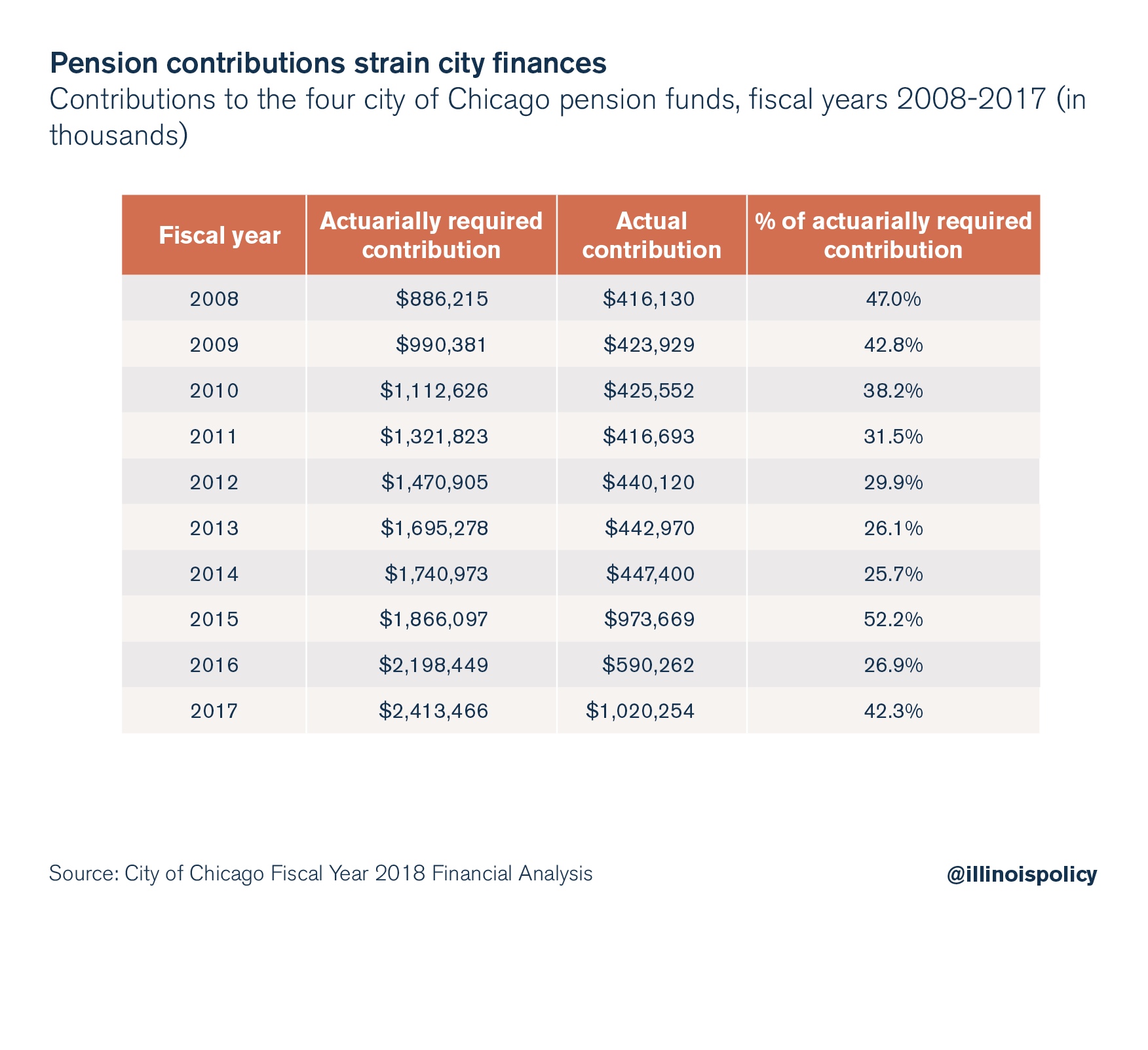

Chicago has struggled to make pension contributions since the last national recession, despite massive tax hikes including a property tax increase of $543 million over four years, new taxes on ridesharing and e-cigarettes, tax increases on water and sewer services and 911 calls, and hikes in fees ranging from garbage collection to building permits.

In addition to these fee and tax hikes, outgoing Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel lobbied in the past for legislation – Public Acts 99-506 and 100-23 – allowing him to make reduced pension contributions from 2015 to 2021 to ease pressure on the city budget in the short term.

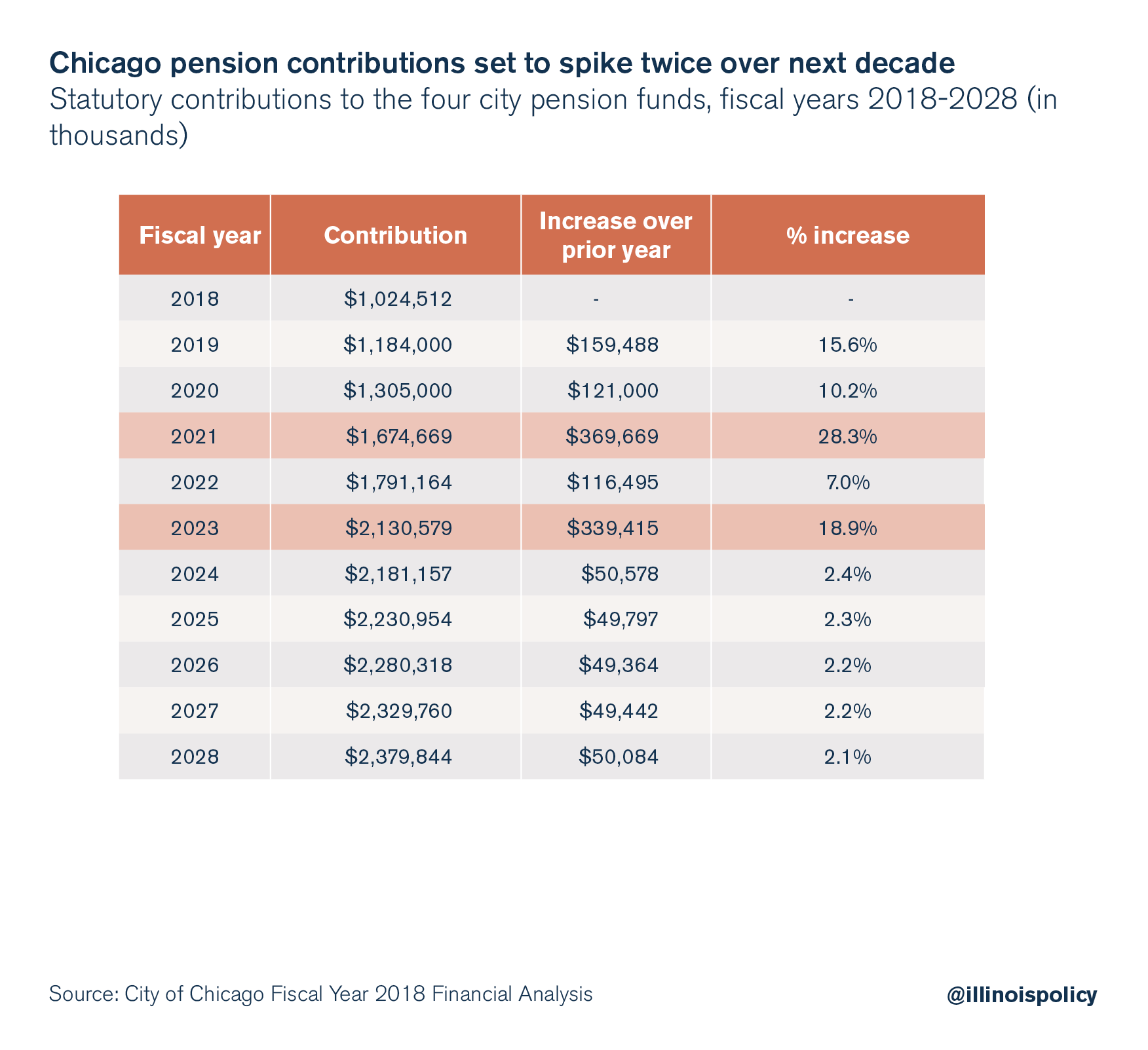

Partly as a result of those artificially low contributions, the next mayor of Chicago will inherit a pension mess with contributions set to spike sharply in the next few years.

Illinois’ and Chicago’s only responsible long-term option for getting out of the mess is meaningful pension reform that starts with a constitutional amendment to allow changes to unearned, future benefits. Changes should include raising retirement ages for younger workers, capping maximum pensionable salary, and doing away with guaranteed permanent benefit increases in favor of a true cost of living adjustment pegged to inflation.

In the short term, the least state lawmakers can do is not hand out any more special perks to well-connected special interests. The courts won’t let them take it back and taxpayers can’t afford it.