Illinois passed a record-breaking income tax hike 3 years ago. Here’s where the money went.

Income taxes rose 32% for individuals and 33% for corporations in 2017, raising Illinois’ total tax burden to at least sixth highest from 10th highest. More than $1.2 billion went to pensions and debt.

On July 6, 2017, the Illinois General Assembly voted to override then-Gov. Bruce Rauner’s veto of a record-setting permanent income tax hike. Personal income tax rates rose 32%, to 4.95% from 3.75%, while corporate income taxes rose 33%, to 7% from 5.25%.

Just three years later, Springfield politicians want permission from voters to again raise taxes. Illinoisans will have the opportunity on Nov. 3 to approve or deny a constitutional amendment allowing Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s $3.6 billion “fair tax” hike. The amendment would eliminate the flat tax protection enshrined in the 1970 state constitution in favor of a progressive tax system, which makes it easier to raise taxes by letting lawmakers charge different rates to different residents, potentially including retirees, based on income.

Voters should be wary of granting state politicians enhanced taxing powers based on the damage from the 2017 tax increase: the state economy has suffered while debt burdens continue to grow.

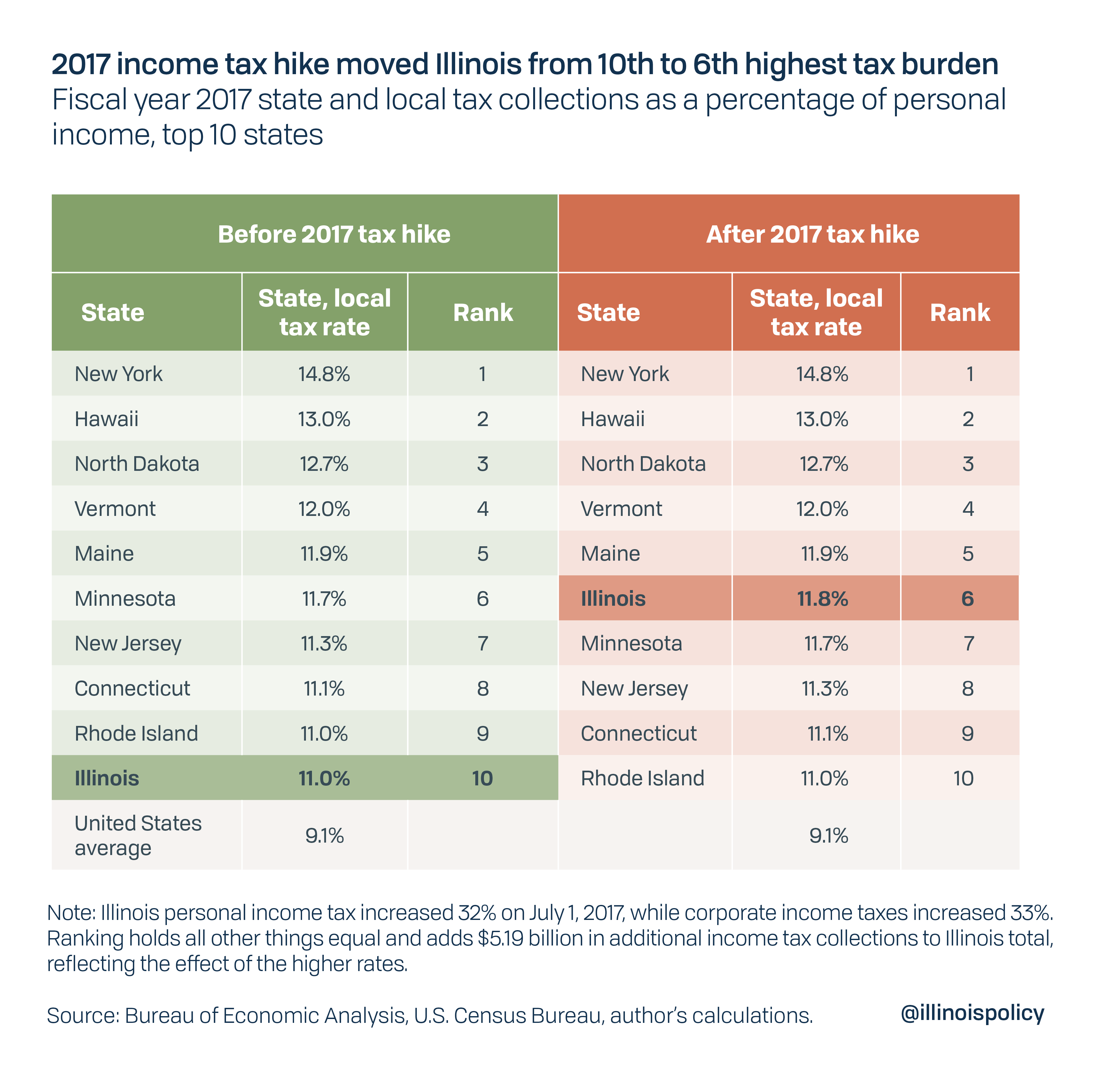

More income tax revenue won’t improve Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation state finances. After the 2017 income tax hike, Illinois’ total tax burden rose from 10th highest in the nation to at least sixth highest, based on the most recent comprehensive data available.

This estimate is based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances. The most recent year of data available is the 2017 survey, which provides data for Illinois state fiscal year 2017. Fiscal year 2017 ended June 30, 2017, just before the income tax hike. The ranking holds all other state tax burdens equal and shows what Illinois’ tax ranking would have been in 2017 had the higher income tax rates been in effect.

An updated ranking for 2018 will likely be available sometime during summer 2020, according to the Census Bureau. Illinois may ultimately rank even higher than estimated, because the trend among states in recent years has been to reduce income taxes rather than raise them as Illinois has done. According to the Tax Foundation, five states cut corporate income taxes in 2019, and six states cut individual income taxes. No state raised income taxes.

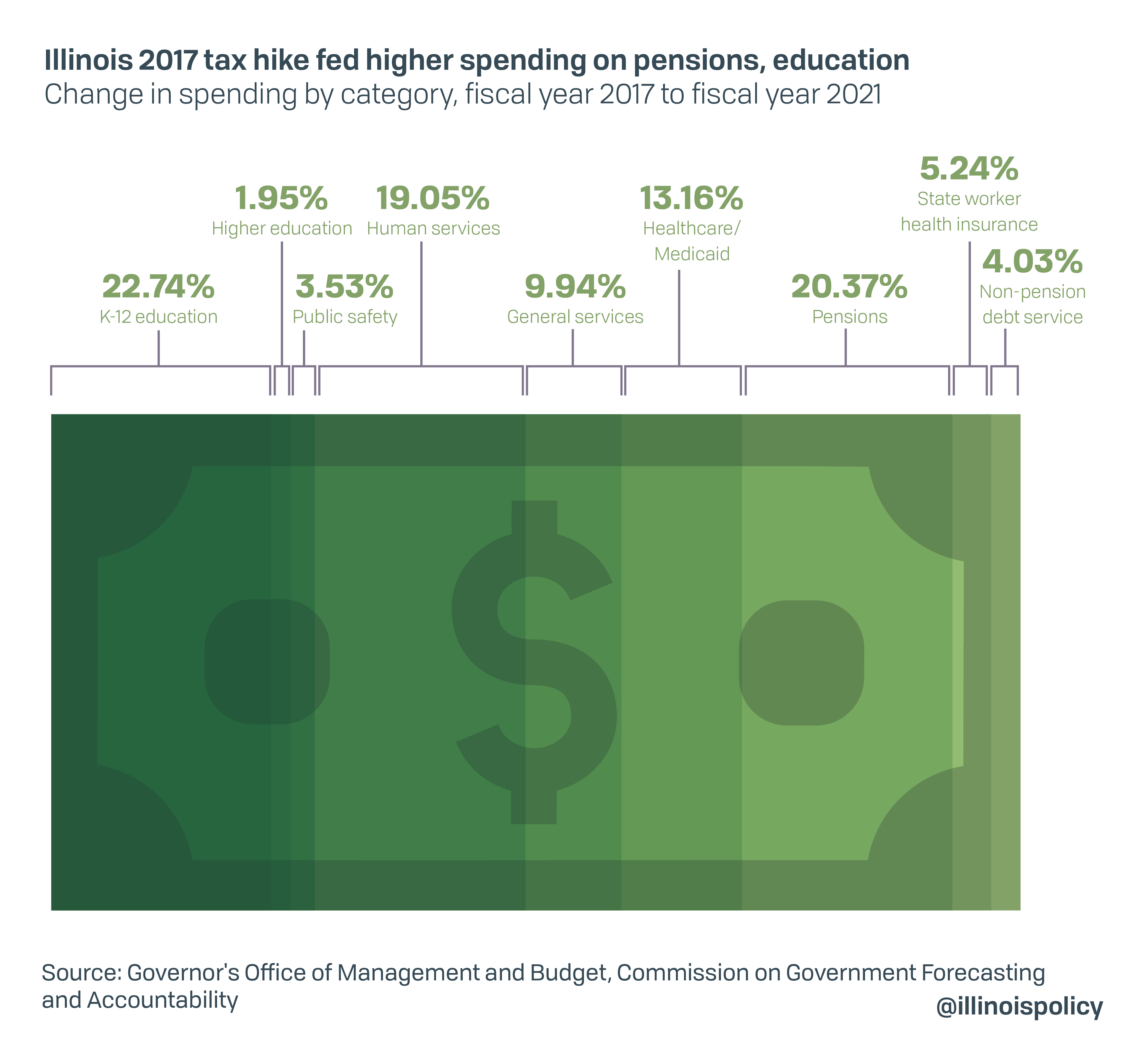

The 2017 tax hike has not translated into more stable state finances or better services for state residents. The state’s credit rating is still the nation’s worst and just one notch above junk status, according to two major credit rating firms. Also, over $1.2 billion of the more than $5 billion in additional revenue has gone to servicing state pension and bond debt, roughly a quarter of the new money raised.

Other spending categories that saw substantial growth from fiscal year 2017 to 2021 include K-12 education and human services. Human services had been drastically cut during the two years the state operated without a budget. Education accounted for 23% and social service for 20% of the new tax hike dollar spending increases.

However, growth in education spending stopped with the latest budget signed by Pritzker, which increased overall spending by $2.4 billion year over year but held education flat, which amounts to a cut when inflation is factored in. That budget includes a $6 billion deficit and $5 billion in potential new borrowing amid lower revenues stemming from the COVID-19 crisis. But state finances had been deteriorating prior to the pandemic.

Illinois has a spending problem, not a revenue problem. It’s one of the highest-taxed states in the nation, but still among the most indebted. More tax increases will ultimately make this problem worse, not better, by driving away the residents and businesses that generate healthy revenue growth in the long term through economic growth.

The state has already lost population for six years running, driven primarily by adults in their prime working years leaving for other states. The most common reason residents give for wanting to leave is the high tax burden, according to public opinion polling conducted for NPR and the University of Illinois-Springfield.

Inefficient spending of existing resources and tax hikes on an already overtaxed population contributed to poor results during the past decade. Illinois ranked 46th in the nation for jobs growth in 2019 and saw the largest labor force decline among states, despite the strong and growing national economy prior to the coronavirus pandemic. Overall, in the decade after the Great Recession, Illinois ranked 38th among states for private sector job creation.

Pritzker’s “fair tax” hike would only make these existing problems worse, taxing over 100,000 small businesses up to 47% more after they were already damaged by the COVID-19 mandates. Economists and other public policy experts nearly all agree you should not hike taxes during a recession.

On Nov. 3, state residents will have the rare opportunity to directly decide how Illinois should move forward. They can give Springfield politicians more power to repeat past mistakes with higher taxes and more wasteful spending. Or taxpayers can say they already pay enough and it’s time for lawmakers to get spending and debt under control with structural reforms.