Illinois needs to end the third-party payer problem for teacher pensions

Illinois’ teacher pension system is structured to allow local school boards to agree to generous contracts, knowing taxpayers across the state will foot the bill. This system should change so that local school boards cover their own pension costs. That way, they will bear the full cost of salary increases they decide on, rather than pushing much of that cost onto unaware state taxpayers.

Illinois has a $74 billion debt hole for teacher pensions, and the third-party payer problem helps explain why.

Here’s how it works in Illinois: Two parties make a financial decision but a third party pays for that decision. This leads to irresponsible spending and unfair costs for the third-party payer.

For example, teachers unions and local school boards agree upon compensation contracts, but taxpayers across the state pay.

Local school boards decide the pay increases that determine the final value of teacher pensions. However, state government pays for those pensions through the Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS. This gives local school boards an incentive to boost the value of teacher pensions to appease local teaching staffs while passing the cost to taxpayers somewhere else. Illinois taxpayers are unwittingly footing the bill for inflated contracts across the state through this financial scheme, which benefits teachers and local school board members.

But the system is set up to incentivize local school boards to behave this way – they get to give out expensive benefits to people in their district while essentially taxing other districts to pay for it. Why not tax people in other districts to give perks to teachers in your district?

That’s why the third-party payer structure doesn’t work: It leads to what’s called “pension spiking,” which is the practice of giving teachers big salary increases right before retirement to boost the pension they will receive. For example, a 10-year teachers’ contract in Palatine includes four consecutive years of 6 percent raises before teachers retire, bumping a teacher with an $80,000 salary up to a $101,000 salary in his or her last four years. The final pension, for which the state pays, is based on an average of these last four years of salary.

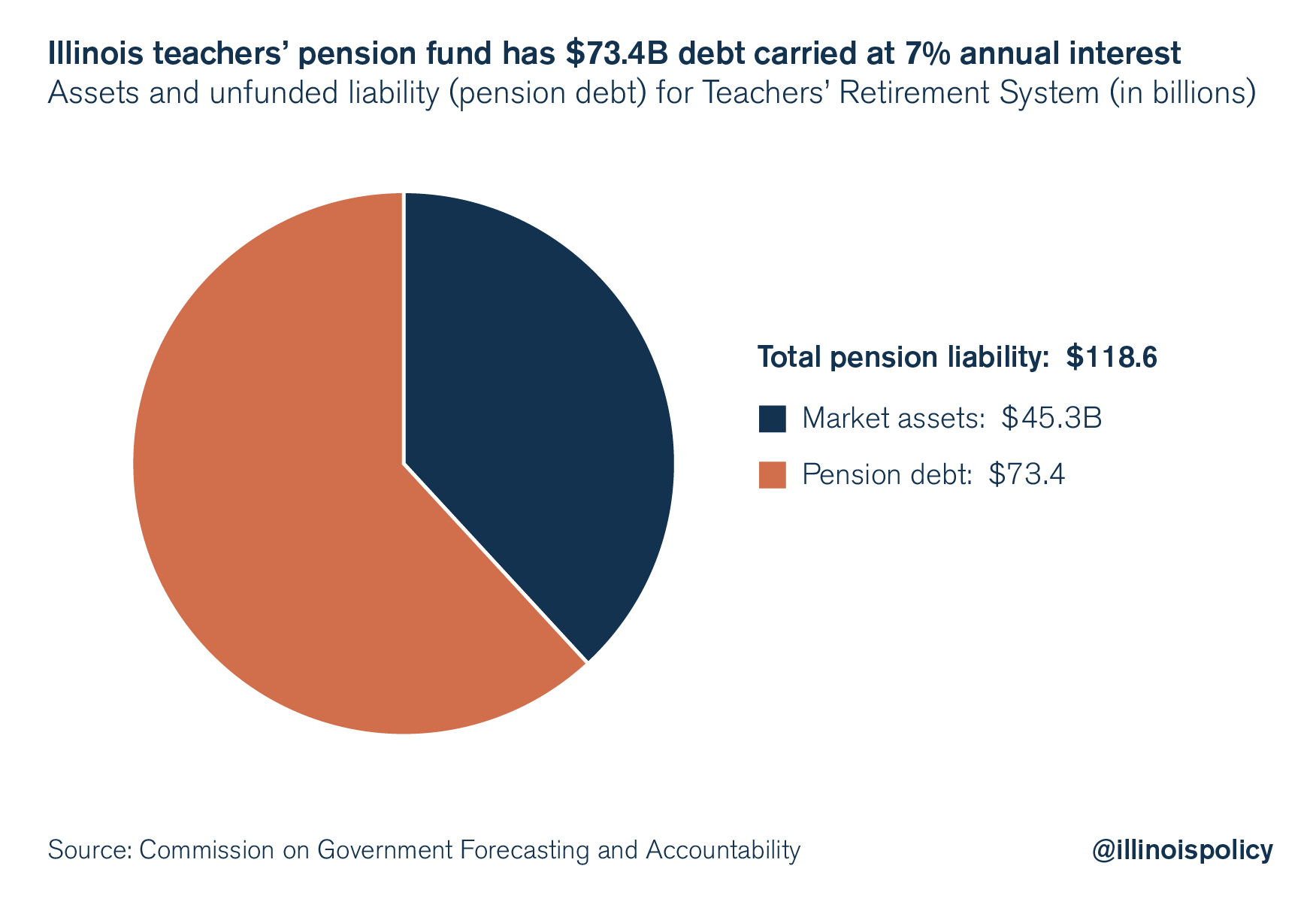

This is one of the reasons Illinois has such an extraordinary debt for teachers’ pensions. Illinois’ teacher pension system is only 38 percent funded. Only $45 billion of assets are on hand to cover a liability currently at $119 billion. This leaves a $73.4 billion debt hole in the TRS pension fund.

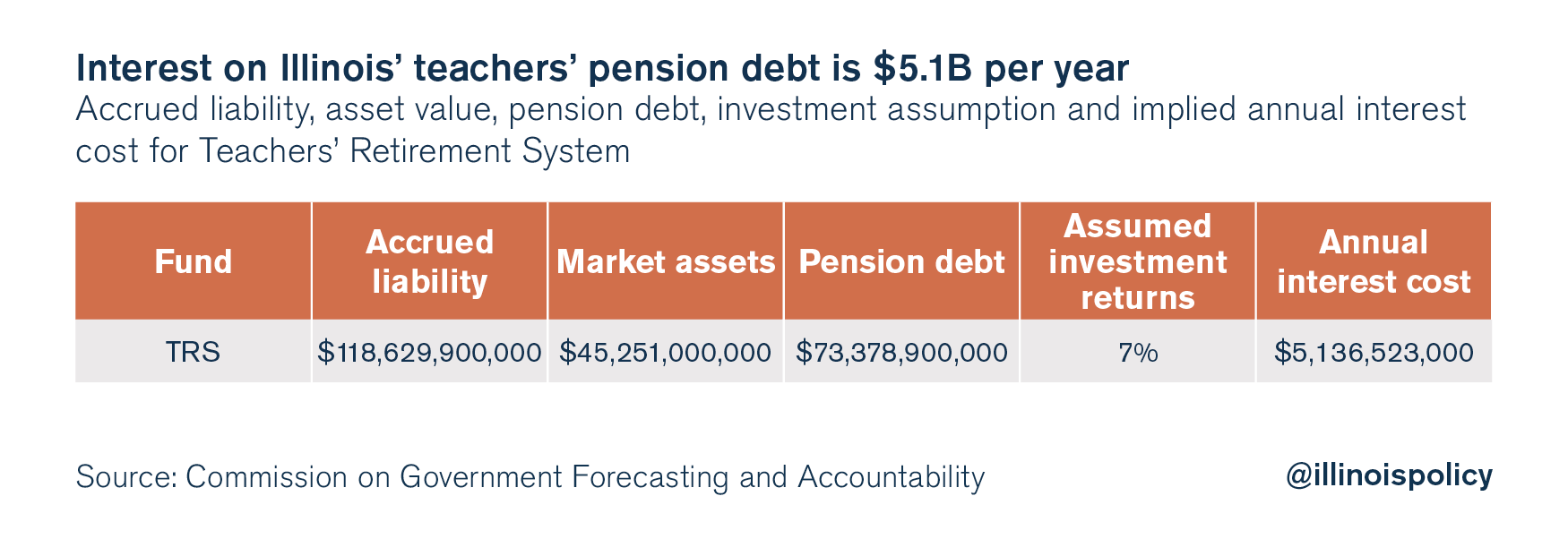

Just the interest cost on the teacher pension debt is $5.1 billion per year. Illinois is not even covering the interest payment, meaning the debt will continue increasing for the foreseeable future.

The way TRS is structured lines up all the local political and financial interests against the financial well being of the state. Requiring local school boards to cover their own pension costs would change this. That way, they will bear the full cost of salary increases they decide on, rather than pushing much of that cost onto unaware state taxpayers.

Politicians already have an incentive problem when they spend public money. As a general rule, people spend their own money much more responsibly than they spend someone else’s money.

The next problem is that school board members can get the benefits of happy teachers and better labor relations with the teachers union by giving teachers this perk paid for by other people.

These school board members do not face local accountability when they juice pensions because local taxpayers don’t directly pay for those pensions. The cost is passed on to state taxpayers generally.

The incentives in Illinois’ pension system are poorly constructed, hurt the finances of the state and are one of the big contributors to Illinois’ extraordinary pension debt. Chicago Public Schools, or CPS, at least takes care of its own pensions, although it receives a special grant from the state to cover the cost. But if (or rather, when) CPS goes bankrupt, that will be a problem for CPS taxpayers rather than taxpayers statewide.

Illinois political leaders should fix this problem statewide by ending the third-party payer problem and having local school boards pick up their own pension costs on a going-forward basis. Local school boards create the cost, so they should pay it. That’s good policy, and good for the state’s finances.