Illinois millennials’ dual debt crises: Who’s to blame?

Baby boomers have saddled young Illinoisans with a grossly unfair burden.

The parallels between the nation’s college debt crisis and Illinois’ $111 billion pension shortfall are obvious and endless – both are rife with irresponsible leaders making promises they can’t keep in the face of ballooning costs. Neither state nor student can default without legal repercussions.

But one of these bubbles may be set to burn millennials more than the other. And it’s not the one selling degrees.

Pensions could very well trump tuition when it comes to impact on young Illinoisans.

This shouldn’t come as a surprise. Illinois’ pension-debt crisis, the nation’s most severe, is structured to hit young people hardest. And it’s making college debt hurt even more.

The scale

While busy entering the workforce to pay for their college tuition, young Illinoisans are being saddled with a massive and ever-growing mountain of public pension debt. Pension costs are crowding out funding for essential services. The state’s credit rating is approaching junk-bond status. And the unfunded pension liability has grown to $111 billion.

To put that number into perspective, the state government would need a three-year shutdown, during which it directed the entire general fund toward pensions, just to break even. Keep in mind that more realistic investment assumptions peg the total unfunded liability at double that number, and Illinois’ local governments have pension crises all their own.

Yes, student debt looms large in Illinois. More than 1.7 million Illinoisans hold student-loan debt, including 70 percent of the state’s class of 2013 – the fourth-highest rate in the country, according to the Institute for College Access & Success’ Project on Student Debt. The average student borrower in the nation’s class of 2014 accumulated $33,000 in debt. And total student-loan debt in Illinois is approaching $50 billion.

But however ugly the college-debt crisis, it is still giving many a solid return on their investment.

That problem is overshadowed by the state’s pension-debt crisis, debt that most young people never signed up to take on in the first place, and which yields a far less substantive benefit than a college diploma.

In Chicago, each household owed more than $36,000 in city and sister-government retiree debt alone as of 2013. State pension debt per Illinois household comes out to more than $23,000.

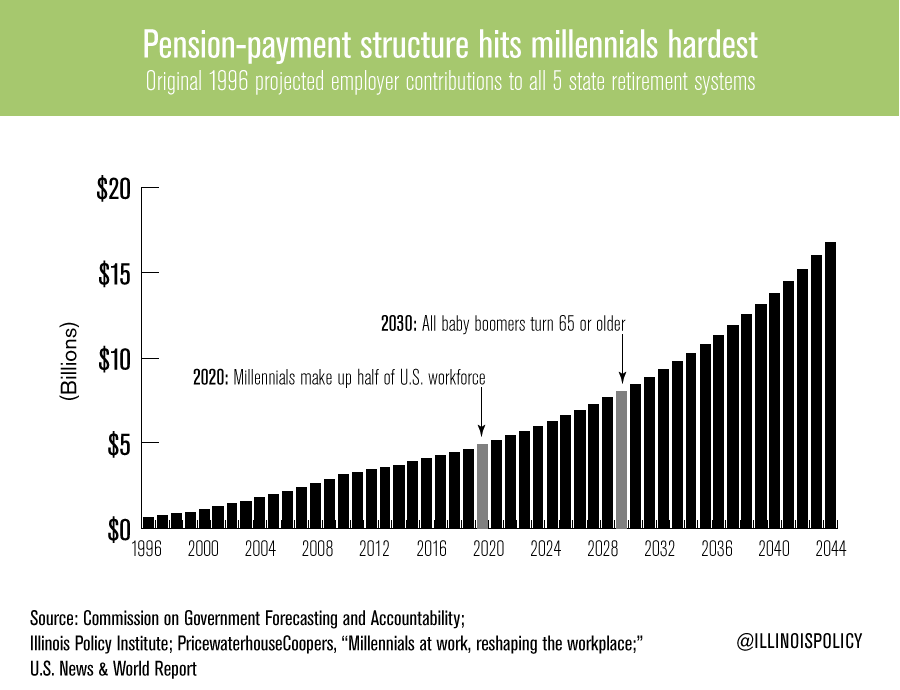

And due to a law passed more than two decades ago, millennials are set to bear the brunt of this mess.

The structure

In 1994, when much of Generation Y was in diapers, then-Gov. Jim Edgar signed into law a 50-year payment structure for the state’s pension system now known as the “Edgar ramp.” It effectively shifted funding responsibility from baby boomers in their prime earning years to millennial cribs, severely backloading payments into a broken system.

Thus far, state lawmakers have funded the pension ramp with massive borrowing and a record tax hike in 2011. The tax increase came in the middle of Illinois’ revival from the Great Recession, effectively knocking the state down to dead last in the nation for recovery of lost jobs.

The suffering

What does all that have to do with diplomas?

From 2006-2013, senior workers in Illinois saw their employment rate rise 2.9 percent, while youth workers’ employment rate dropped 8.4 percent. Millennials who took on college debt to strive for better opportunities in Illinois graduated into an economy increasingly unable to provide them.

Some policymakers suggest further tax hikes to fund the pension ramp. But raising the cost to do business in the state with the worst job-creation rate in the Midwest and a massive out-migration problem would serve only to further limit opportunities for young workers.

Also, should the state boost revenues to bail out these pension systems again (remember, most of the state’s $35 billion in revenue from the temporary tax-hike enacted in 2011 went to fund pensions), millennials would be footing the bill for irresponsible behavior dating back to before they were born in return for an equal or diminished quality of government services.

To put it simply, the harmful effects of the state’s spending habits – especially in the case of its poorly run pension systems – crippled Illinois’ economy, leaving those with college debt less able to pay it off. Repeating this mistake would be a slap in the face to the young Illinoisans now entering the private-sector workforce.

But millennials in the private sector aren’t the only ones set up to suffer. Young public-sector workers are too, albeit in a different way.

State employees hired in or after January 2011, dubbed “Tier 2” members of the pension system, will receive a far less generous pension benefit than their elders, getting lower cost-of-living-adjustment raises, a higher retirement age and a cap on their pensionable salary among other, lesser perks. And they’re projected to fund the entire cost of their own retirement benefits without help from taxpayers, plus the legacy costs of “Tier 1” members with more generous pensions.

That’s right, the young employees entering the less generous Tier 2 system are, in some cases, held responsible for bailing out higher-end pensions for baby boomers.

WirePoints founder and co-chairman of Gov. Bruce Rauner’s Innovate Illinois Advisory Committee, Mark Glennon, recently detailed this inequity within the Illinois Teachers Retirement System, or TRS, which accounts for more than half of the state’s total pension debt. He revealed that Tier 2 employees in TRS pay an extra 2.4 percent out of their paychecks to bail out their Tier 1 peers, citing the system’s Winter 2015 Report.

“It’s as if a private employee funded his entire 401(k) with no contribution from his employer, and was forced to pay an extra amount to fund some other guy’s much larger account,” Glennon wrote.

For these millennial teachers, money that could have been used to pay down debt they took on to earn their teaching degrees instead goes to fund a retirement system from which they will receive no benefit.

Going forward, if Rauner gets his way, all future work starting July 2015 will fall under the Tier 2 scheme.

This is far from the only age-determined disparity within these systems.

Not every recent college graduate entering the field of education, for instance, would like to work for a public school – or even in the teaching profession – for most of their professional lives. But the quality of their retirement depends on them doing so under Illinois’ defined-benefit system. If a young public-school teacher leaves the profession, moves to another state or switches to a private or charter school before fully vesting in their retirement – which takes 10 years – the pension benefits they paid into will not travel with them.

But this isn’t so for their peers who entered the private sector upon graduating. In most cases, they can take all the money they and their employer have both contributed to their retirement fund wherever they want, whenever they want.

The solution

Structural reform of Illinois’ pension systems is urgently needed. Bold changes are necessary if young workers are to survive the state’s clash with fiscal reality.

Policy-wise, this means giving all new government workers control over their own retirements with 401(k)-style plans, and allowing young employees trapped in the blatantly unfair Tier 2 system the opportunity to opt out and control their own retirements in the same way.

Politically, millennials must direct the same critical eye they cast toward entrenched higher-education interests toward politician-run retirement systems. Illinois lawmakers have thus far only shown concern for constituents in their own age bracket, wildly mismanaging the systems to the detriment of future generations.

Taking on college debt to move up the economic ladder is still a worthwhile bet for many millennials. The state’s pension problems, on the other hand, are set to bankrupt their government’s fiscal future.