Illinois lost 1 resident every 7 minutes in 2013

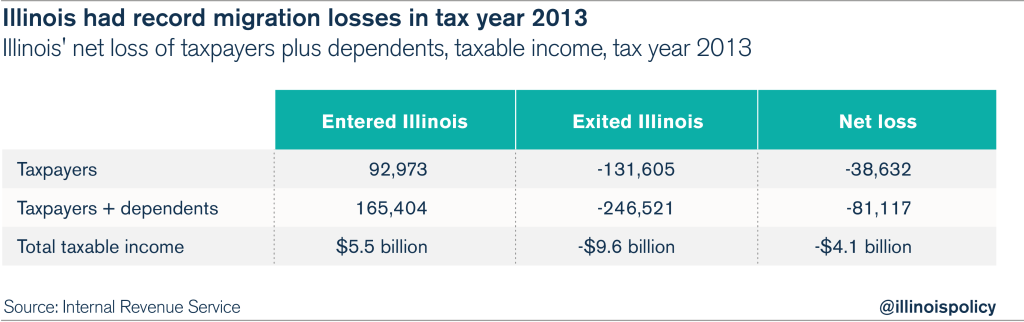

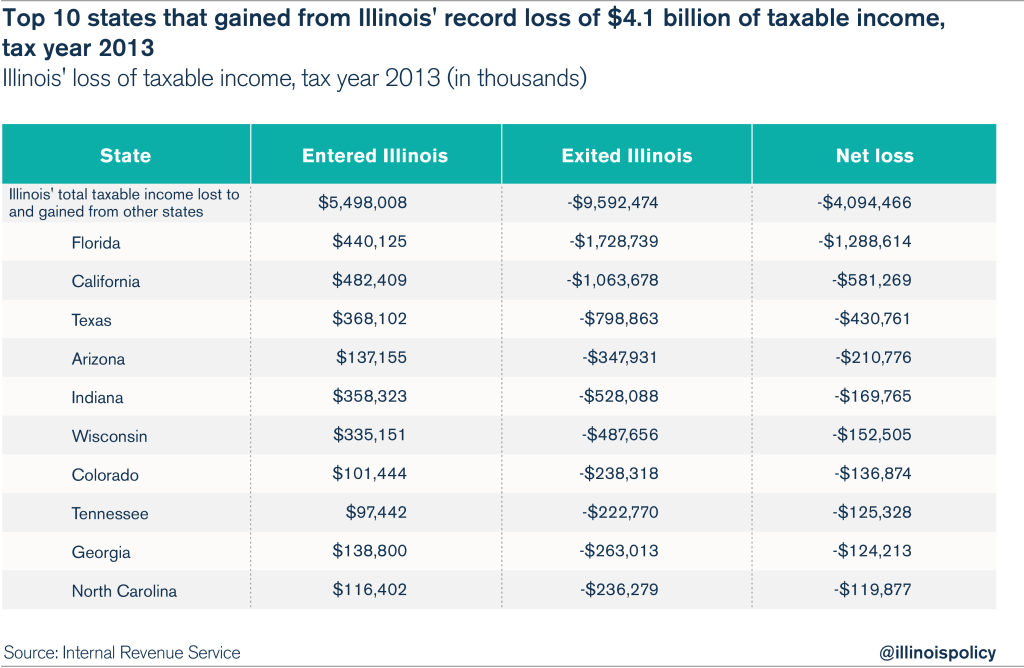

Newly released IRS data show Illinois lost on net over 81,000 taxpayers and their dependents, and $4.1 billion of annual taxable income to other states in 2013.

Illinois lost 81,000 people and $4.1 billion of annual taxable income during the 2013 tax year on net, by far the worst loss Illinois has ever seen, according to newly released IRS migration data. This amounts to losing one resident and $50,000 worth of annual taxable income every 6.5 minutes. The IRS data compare where taxpayers filed tax returns in spring 2014 with where they filed tax returns in spring 2013.

Illinois is also home to the worst employment recovery in the country since the Great Recession, and is the only state in the region where more people have begun receiving food stamps than have started jobs since the Great Recession ended.

Out-migration from Illinois has spiked as taxes have shot up and job creation has faltered. During the first three years of Illinois’ 2011 income-tax hike, Illinois lost increasing numbers of people and income:

- 2011: 49,728 taxpayers plus dependents and $2.5 billion of annual income

- 2012: 66,922 taxpayers plus dependents and $3.8 billion of annual income

- 2013: 81,117 taxpayers plus dependents and $4.1 billion of annual income

Illinois lost one person and $48,000 of annual income on net every 10 minutes in 2011. By 2013, that rate had accelerated to one person and $50,000 of annual income every 6.5 minutes.

All told, Illinois sustained a net loss of 200,000 people and $10.4 billion of annual taxable income from 2011-2013. That makes the first three years of the record 2011 income-tax hike Illinois’ worst three years ever recorded for loss of taxable income.

The IRS numbers paint a dismal picture for Illinois:

1. Illinois lost a record number of taxpayers, dependents and annual income in 2013.

During the 2013 tax year, Illinois sustained net losses of 38,600 taxpayers, 81,100 taxpayers plus dependents, and $4.1 billion of annual adjusted gross income.

2. Illinois lost a record number of taxpayers, dependents and annual income in 2013.

During the 2013 tax year, Illinois sustained net losses of 38,600 taxpayers, 81,100 taxpayers plus dependents, and $4.1 billion of annual adjusted gross income.

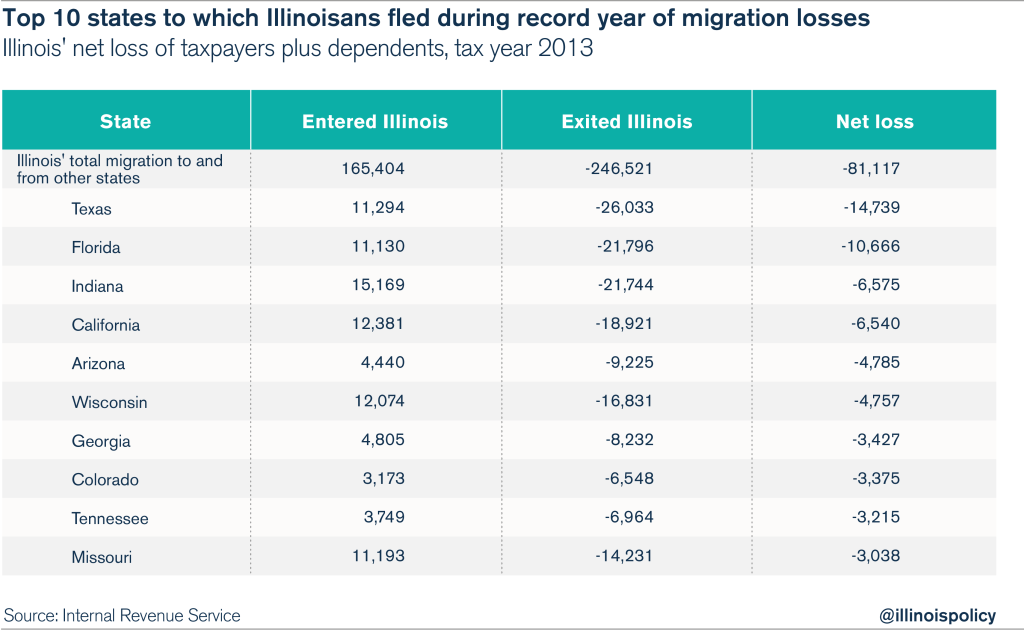

3. Illinois lost state-to-state migration battles with 45 of 50 states, plus Washington, D.C., in tax year 2013.

Texas’ strong jobs growth and lower cost of living attracted more Illinoisans than did any other state – the Lone Star State gained a record of nearly 15,000 Illinoisans on net in 2013. The other states to which large numbers of Illinoisans flocked were primarily warmer states and neighboring states with better jobs growth.

For information on Illinois’ taxpayer migration to and from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, click here.

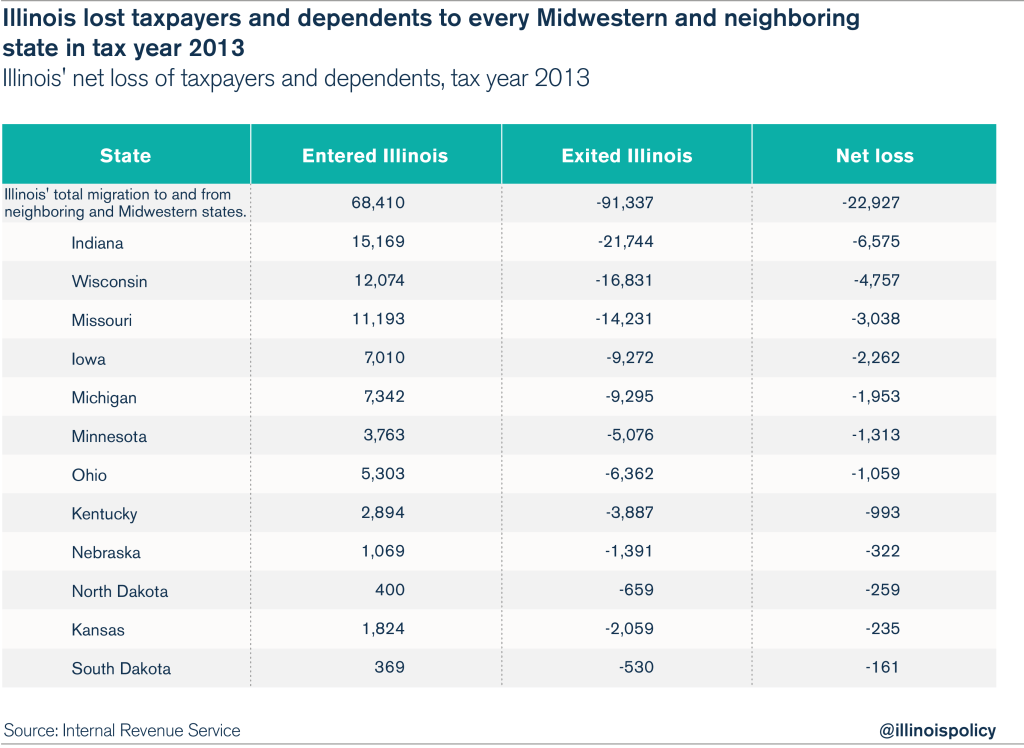

4. Illinois lost migration battles with every neighboring state and every state in the Midwest.

Illinois’ regional migration losses prove that Illinoisans are heading for states with better economic climates and job opportunities, not just warmer weather. Even Rust Belt states like Michigan and Ohio, which have lost people to Illinois in the past, now gain Illinoisans every year.

5. Illinois lost annual income to 43 of 50 states, plus Washington, D.C., in tax year 2013.

Illinois lost annual income to a vast majority of states because its residents are pursuing better economic opportunities elsewhere.

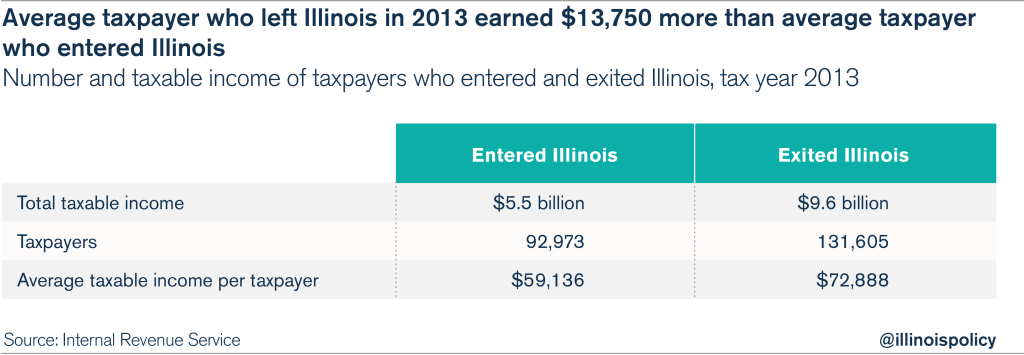

However, higher-income Illinoisans move for a variety of reasons, and therefore, Illinois’ migration of income does not perfectly align with its migration of residents. For example, Texas ranks No. 1 in gaining people from Illinois, but ranks No. 3 in gaining Illinois income.

Illinois’ income-tax hikes would have encouraged higher-income earners to relocate to zero-income-tax states like Florida, Texas and Tennessee. And although states like Florida and Arizona do outpace Illinois in jobs and economic growth, the magnitude of income losses to Florida and Arizona are influenced in part by retirement migration, which is often higher-income migration.

Illinois’ migratory losses to Texas and California provide an interesting comparison. Both Texas and California have experienced a more robust economic recovery than Illinois, with Texas’ energy boom and broad economic growth outpacing California’s tech-driven growth. Texas is attracting Illinoisans through job creation at all income levels, which likely explains why the Lone Star State ranks No. 1 for gaining Illinoisans.

By comparison, one of the great success stories of the post-recession American economy is the growth of technology firms in Silicon Valley, along with related service providers. High-earning engineers and tech-sector workers have likely moved to California from Illinois, which would explain why Texas gained more people from Illinois, but California gained more income.

For information on Illinois’ income losses with respect to all 50 states and the District of Columbia, click here.

The IRS data show that Illinois’ No. 1 budget problem is taxpayers fleeing the state, and that only structural economic reforms that lead to job creation can keep Illinois’ residents working and paying taxes in Illinois. The IRS data also reveal the folly of a state’s trying to tax its way out of its revenue problems. Gov. Bruce Rauner is demanding structural economic reforms because Illinois will never end its annual budget crises without sustained growth.

The alternative to Rauner’s proposal is to repeat the 2011 disaster: more massive tax hikes with no reform. This path leads inevitably to less economic growth, fewer jobs, more out-migration and even worse budget problems down the road.

Taxpayers move to where they can best fulfill their dreams, taking jobs and economic growth with them. Until Illinois implements structural reforms, taxpayers will continue to view the Land of Lincoln in the rearview mirror.

Note: IRS migration data should not be confused with U.S. Census Bureau migration data. The IRS data are an important input for the Census Bureau’s data, but the census data usually show larger changes in the number of people moving. This is because IRS data capture only taxpayers and their dependents, while the Census Bureau also estimates the movement of people who are not filing taxes, such as new students out of college.