Illinois bill would slow transition from lawmaker to lobbyist

Most states require a wait before lawmakers become lobbyists. Recent federal probes point out the need for Illinois to do the same.

In Illinois, a state lawmaker could retire on Tuesday and be in the state Capitol working for a lobbying firm by Wednesday.

Most states require a “cooling off” period before lawmakers can embark on a lobbying career. But not Illinois.

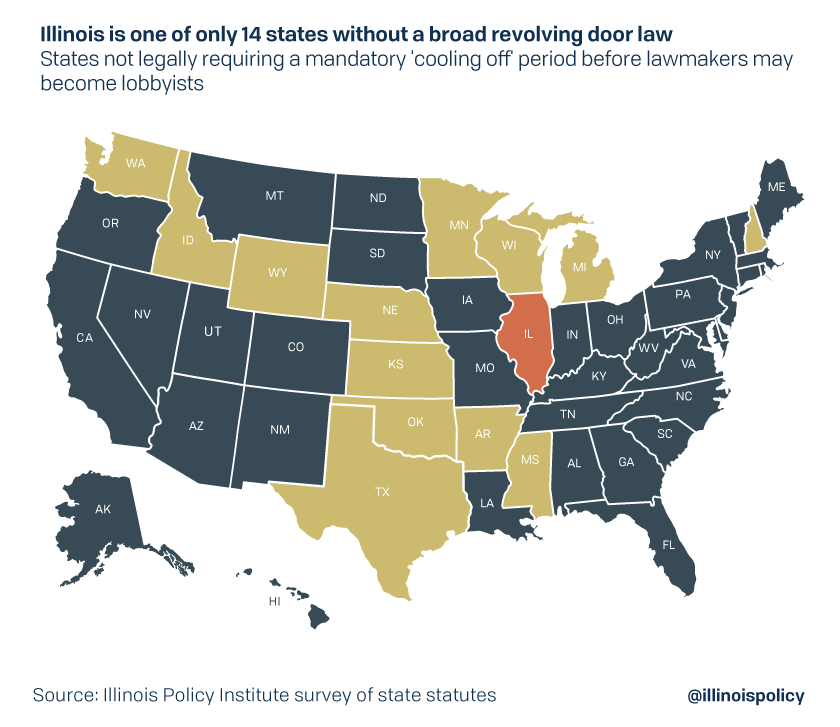

The Land of Lincoln is one of only 14 states that do not have broad “revolving door” laws that prohibit someone going immediately from lawmaker to lobbyist, according to an Illinois Policy Institute survey of state statutes.

The lack of a cooling off period encourages lawmakers to prioritize building relationships with special-interest groups that can help them in life after the legislature, rather than to serve constituents.

Given the recent lobbying-related scandals in the Illinois General Assembly, instituting restrictions on the revolving door is an obvious place to start cleaning up corruption. Federal investigations, raids and charges involving lobbying make the case for keeping lawmakers focused on their constituents’ interests while in office.

The majority of states require a “cooling off” period of one to two years before former lawmakers can become lobbyists, but some take that a step farther. Florida, for example, will require a six-year cooling off period starting Dec. 31, 2022.

Even among the states that do not prohibit the revolving door, some have more restrictions than Illinois on what lawmakers can do after leaving office.

In Kansas there is a two-year waiting period if a state officer was involved in any contracts made between the state and a prospective employer. Michigan has a ban on lobbying, but only for the remainder of the term of a politician who resigns from office.

The Prairie State merely requires a limited one-year cooling off period before lawmakers can accept compensation from companies or organizations with whom they had been involved in awarding contracts amounting to $25,000 or more. Illinois has no blanket laws preventing lawmakers from lobbying immediately after leaving office.

The revolving door from lawmaker to lobbyist creates the appearance that politicians are making deals with special interests rather than advancing the interests of those they represent. So in a state with a recent stream of corruption headlines in the news, it looks especially bad. The practice is part of a larger problem that has led to Illinois’ designation as the second-most corrupt state in the nation. Establishing a “cooling off” period in line with the rest of the nation is one key way Illinois can improve.

That is the aim of Senate Bill 2314, which was filed Nov. 21 by state Sen. Heather Steans, D-Chicago. It would prohibit former lawmakers from acting as lobbyists for two years after they leave office. This legislation would put Illinois in line with the vast majority of states, and is an important step toward cleaning up the state.