Illinois became less competitive after Blagojevich’s 2005 workers’ compensation bill

This blog is the fifth part of a series that explores Illinois’ workers’ compensation system, the state’s inadequate reforms, and opportunities policymakers should seize now to make the system less costly and more effective for employers and workers alike.

Former Gov. Rod Blagojevich and the Illinois General Assembly passed workers’ compensation legislation in 2005 with the stated intention of making Illinois more competitive for jobs and businesses. The results of Blagojevich’s legislation and administrative control turned out quite the opposite, as the cost of doing business in Illinois skyrocketed.

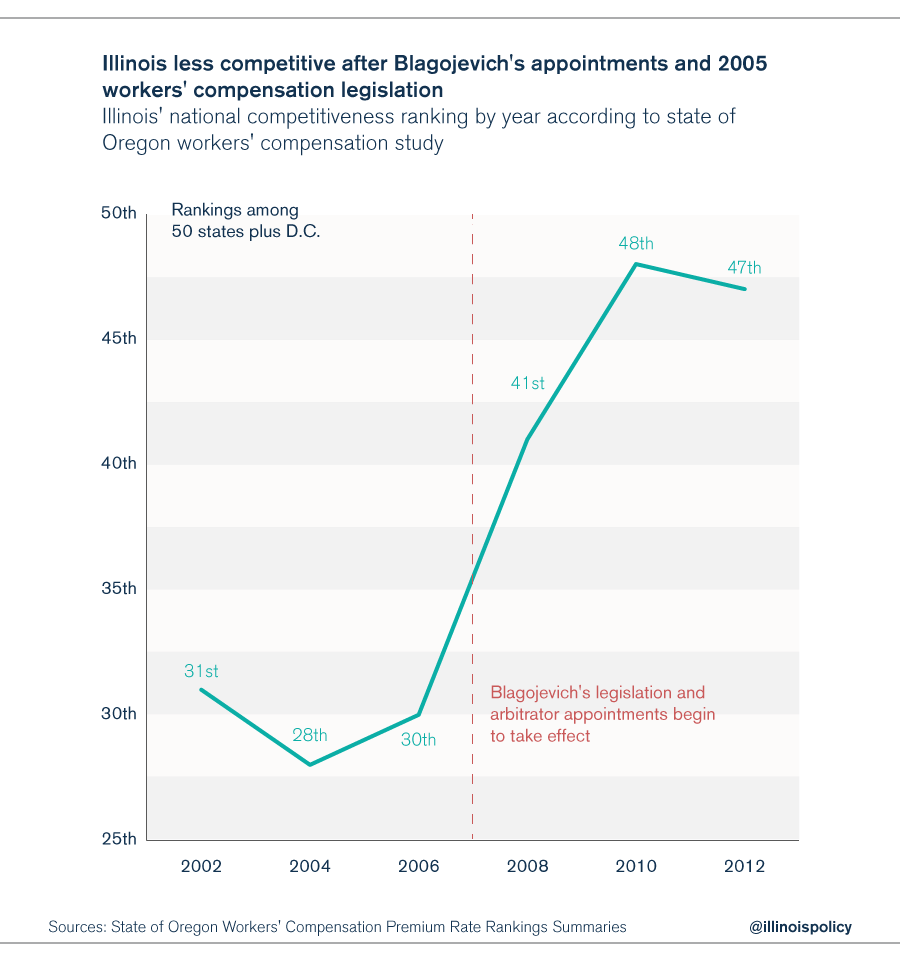

According to a study by the state of Oregon, Illinois ranked as the 31st-most-competitive state for workers’ compensation costs in 2002, the 28th-most- competitive in 2004, and the 30th-most-competitive in January 2006, before the effects of Blagojevich’s legislation had begun to affect system costs. In other words, Illinois was not too much worse than middle of the pack in the years before the 2005 reforms started taking effect.

When the 2005 reforms took effect, Illinois’ ranking plummeted, and the 2008 state of Oregon rankings showed Illinois as the 41st-most-competitive state. By 2010, Illinois’ rank had dropped to No. 48 of the 50 states, plus the District of Columbia, and in 2012, Illinois hovered at the No. 47 spot in the competitiveness rankings.

What happened that made Illinois become so much less competitive so quickly? There are at least three parts to this answer, all of which the governor and the General Assembly can address through executive action and legislative reforms.

- The 2005 law empowered Blagojevich to appoint arbitrators and other workers’ compensation officials who would make decisions that would influence workers’ compensation claims. An ally of the Illinois trial bar, Blagojevich had strong political connections to trial lawyers who wanted their friends deciding workers’ compensation claims. A system staffed by trial lawyers will naturally result in litigator-friendly costs. Gov. Bruce Rauner can fix this problem by appointing different arbitrators, and as of writing, the process of cleaning house is underway.

- The Illinois Chamber of Commerce described a second factor in the costliness of Illinois’ workers’ compensation system in a research report, “The Impact of Judicial Activism in Illinois,” which presents workers’ compensation judicial rulings from an employer’s perspective. The report details some scarcely believable judicial rulings in workers’ compensation cases, such as the following:

- A worker who received compensation as a traveling employee when she slipped and fell on the ice in her own driveway (2013)

- A worker who received compensation as a traveling employee for injuries in a car accident in which he had used a company car to travel home after running a personal errand (2010)

- A worker who received compensation after injuring his shoulder while ramming it against a vending machine in order to shake loose a bag of chips for a co-worker. This worker was covered under a so-called Good Samaritan concept, because he was trying to do a good deed for his friend. (2009)

A number of the problems implied by these rulings, such as the need to narrow the definitions of “causation” and “traveling employee,” are addressed in Rauner’s workers’ compensation reform legislation.

- A third factor, which the General Assembly should address through new legislation, is the 2005 reform legislation itself, which resulted in several cost drivers. Here are some examples of those cost drivers and potential fixes for them:

- The 2005 bill instituted an approximately 7.5 percent across-the-board increase in indemnity payments for “permanent partial disability” injuries, measured by the number of weeks of wages that would be awarded. For example, an award for a thumb injury was increased to 76 weeks from 70 weeks of wages.

The General Assembly can undo the cost-increasing effects of the 2005 legislation by simply rolling back the number of weeks in awarded wages to pre-2005 levels.

- The 2005 bill raised the maximum award for certain injuries to the greater of 25 years of wages or $500,000 from the greater of 20 years of wages or $250,000.

Lawmakers can change this maximum award to a more moderate amount such as the greater of 20 years of wages or $400,000, which would still constitute an increase in benefits from pre-2005 levels.

- Finally, the 2005 bill mandated that when workers who earn below certain lower wage thresholds are injured on the job, 100 percent of their lost wages must be replaced, untaxed. This equals an effective pay hike for these workers, many of whom are part-time employees, which defeats the purpose of the workers’ compensation system and creates a disincentive to return to work.

In general, across the workers’ compensation system, injured workers have two-thirds of their lost wages replaced, untaxed. However, for workers who earn less than $220-$330 per week, depending on their number of dependents, all lost wages are replaced, tax-free. When an injured worker receives more take-home pay by staying home, he has a strong disincentive to return to work. This also drives up the cost of any indemnity settlements and wage replacements that are based on these minimum replacement rates.

One option for reform would be to split the difference for these minimum wage-replacement ratios between what the majority of workers receive (two-thirds of lost wages, untaxed) and what these lower-wage workers currently receive (100 percent of lost wages, untaxed). For example, workers who fall into these lower wage categories could receive five-sixths of their lost wages, untaxed. This would still provide a cushion to protect lower-wage workers while removing the effective pay hike that current law gives these workers for being injured.

Blagojevich’s 2005 workers’ compensation legislation and the Blagojevich administration’s policies in general put Illinois businesses and manufacturers at a disadvantage by driving workers’ compensation costs to unsustainably high rates. Policymakers should repeal the mistakes made by the Blagojevich administration, particularly those in the 2005 law, to put Illinois back on the path to growth.

For previous pieces, see: (1) the introduction to this series, which provides an overview of Illinois’ workers’ compensation system and the costs and regulatory burdens it imposes on employers; (2) the article on the 2005 law, which discusses the attempted reform of the workers’ compensation system’s medical fees and billing, as well as the provision of benefits increases and anti-fraud measures; (3) the article regarding the 2011 law, which outlines some of the attempts to control costs, including medical-fee reductions and the enhancement of employers’ ability to negotiate fees for medical services; and (4) the article on physician dispensing, which discusses the unintended, detrimental consequences of the 2011 reform law’s changes to physician dispensing of prescribed medication directly to workers’ compensation patients.