Illinois 13-year-old charged with eavesdropping felony for recording meeting with principal

Illinois’ eavesdropping law is one of the nation’s most severe, but leaves ample room for ambiguity.

Paul Boron is 13 years old.

And he’s facing a felony eavesdropping charge that could change the course of the rest of his life.

His story stands as another chapter of controversy surrounding an eavesdropping law some experts have criticized as ripe for abuse and misapplication.

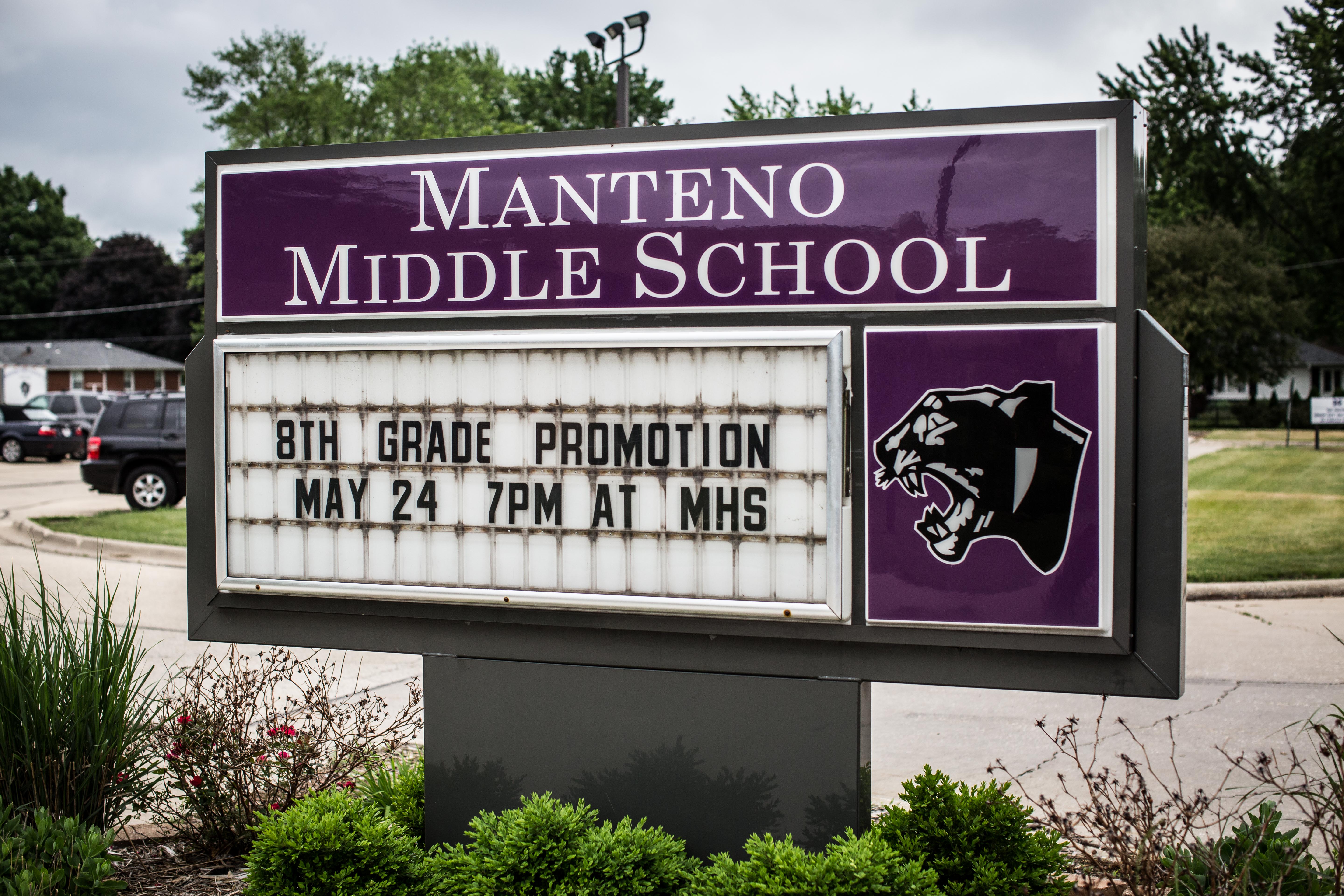

On Feb. 16, 2018, Boron was called to the principal’s office at Manteno Middle School after failing to attend a number of detentions. Before meeting Principal David Conrad and Assistant Principal Nathan Short, he began recording audio on his cellphone.

Boron said he argued with Conrad and Short for approximately 10 minutes in the reception area of the school secretary’s office, with the door open to the hallway. When Boron told Conrad and Short he was recording, Conrad allegedly told Boron he was committing a felony and promptly ended the conversation.

Two months later, in April, Boron was charged with one count of eavesdropping – a class 4 felony in Illinois.

“If I do go to court and get wrongfully convicted, my whole life is ruined,” said Boron, who lives with his mother and four siblings in Manteno, Illinois, an hour southwest of Chicago. “I think they’re going too far.”

In his petition to bring the charge, Kankakee County Assistant State’s Attorney Mark Laws wrote that Boron on Feb. 16 “used a cellphone to surreptitiously record a private conversation between the minor and school officials without consent of all parties.” Members of the Manteno Community Unit School District No. 5 board, Conrad and Short have not responded to requests for comment on the incident.

“We cannot comment on a pending matter, and we are not authorized to release confidential student information to the press,” district Superintendent Lisa Harrod wrote in an email.

Boron’s mother, Leah McNally, was shocked when she learned about the charge against her son.

“It blew my mind that they would take it that far … I want to see him be able to be happy and live up to his full potential in life, especially with the disability he has,” she said. Her son is legally blind in his right eye.

The Manteno district handbook outlines that students are not allowed to record interactions with other students at school. It also notes that a video monitoring system may be in use in public areas of school buildings. But it does not detail when it is appropriate for students to record teachers or administrators.

Illinois’ eavesdropping law is similarly gray on the matter, which has led to a number of contentious legal battles and attempts at reform in recent years.

‘We know it when we see it’

For years, Illinois has been home to one of the nation’s most severe and controversial eavesdropping laws.

Christopher Drew, an artist arrested for selling artwork on a Chicago sidewalk in 2009, was charged with a felony for recording the incident. In 2010, Bridgeport resident Michael Allison was charged with a felony for recording his own court hearing after the court did not provide a court reporter. The same year, Chicagoan Tiawanda Moore was charged with a felony for recording conversations with Chicago Police Department investigators regarding her sexual misconduct complaint against an officer.

These cases arose because the law established Illinois as an “all-party consent” state, where, essentially, recording any conversation unless all parties consented was a felony offense. Federal law and a majority of states allow for one-party consent.

In March 2014, the Illinois Supreme Court struck down Illinois’ eavesdropping law, holding that it “criminalize[d] a wide range of innocent conduct” and violated residents’ First Amendment rights.

But during lame-duck legislative session in December 2014, the Illinois General Assembly passed and Gov. Pat Quinn signed a new eavesdropping law. In the wake of the Supreme Court ruling, lawmakers included changes aimed at allowing residents to record interactions with police, for example, but kept intact the “all-party consent” provisions and introduced a difficult-to-gauge standard for when a person must get consent for recording.

Specifically, the new law made it a felony to surreptitiously record any “private conversation,” defined as “oral communication between [two] or more persons” where at least one person has a “reasonable expectation” of privacy.

Boron’s case raises a number of questions critics pointed out in the debate surrounding the 2014 law. Namely, when does someone have a “reasonable” expectation of privacy? And is it fair to expect Illinoisans to know where to draw that line in their everyday lives?

One of the eavesdropping law’s sponsors, former state Rep. Elaine Nekritz, responded to criticisms of the law’s clarity with an especially vague remark. How does one tell when there is a reasonable expectation of privacy when recording police officers, for example? “We’ll know it when we see it,” she told the Chicago Reader.

That’s not likely to serve as any comfort to a 13-year-old facing criminal charges.

“In a public school setting, what kind of reasonable expectation of privacy can there be for a principal interacting with the public?” asked Wayne Giampietro, former president of the Illinois-based First Amendment Lawyers Association.

Quincy lawyer Saleem Mamdani, who prepared a presentation for an Illinois State Bar Association seminar regarding Illinois’ eavesdropping law, also expressed disbelief.

“With authority figures, if you are engaging in official action, how are you expecting that to be private?” he said. “You are relying on the fact that you had this conversation in imposing current or future discipline.”

Mamdani believes Illinois’ eavesdropping law could be ripe for challenge in the courts, especially given the ubiquity of recording devices on smartphones and devices such as Amazon Alexa and Google Home.

Beyond arguments about expectations of privacy, a sexual misconduct scandal that recently came to light in Chicago shows why lawmakers might seek to empower students to record interactions with the adults who run their schools.

Permanent record

For Terri Miller, president of the nonprofit Stop Educator Sexual Abuse, Misconduct and Exploitation, students’ ability to record interactions with authority figures can be crucial in exposing wrongdoing.

“What child is going to come forward and try the same thing?” she said when notified of Boron’s case. “It will have a deterrent effect on children to report, to speak up when something is wrong.”

Indeed, Boron’s eavesdropping charge comes amid intense criticism of administrators in the state’s largest school district for their handling of misconduct. A June investigation by the Chicago Tribune revealed gross shortcomings in Chicago Public Schools’ handling of sexual abuse allegations from students across the city.

Chicago Board of Education President Frank Clark is moving to transfer an investigation into the abuse allegations to the CPS inspector general’s office from the city law department, which has been criticized for harboring conflicts of interest as it’s also tasked with defending the district should an abused student file a lawsuit.

Looking forward

Boron isn’t quite sure what he wants to be when he grows up. He’s interested in serving in the military, but his vision impairment limits his opportunities there. And if he’s exposed to the juvenile justice system his opportunities could narrow further.

“It would be heart-wrenching,” McNally said of the possibility that her son is found guilty.

“He didn’t do anything wrong, and for him to be snatched from his family, the emotional impact that’s going to have … it’s just going to follow him throughout his years.”

Given the zeal with which Illinois prosecutors have enforced the state’s eavesdropping law, reform from the Statehouse may be Boron’s best hope.