How licensing puts the hurt on lower-income Illinoisans, entrepreneurs

In Illinois, a cosmetologist must complete 350 days of educational training, but an EMT can be licensed after just 37.

State licensing requirements are often irrational, inconsistent and do little to protect the public, while imposing heavy burdens on residents trying to earn a living. And Illinois is no exception.

That’s according to new research from the nonpartisan Institute for Justice, or IJ.

Occupational licensing is often irrational, inconsistent and costly

IJ released a report in November that examines the licensing of 102 lower-income occupations among the 50 states and Washington, D.C. These occupations include jobs such as manicurist, locksmith and barber. Researchers ranked states according to the number of occupations licensed, as well as the burden imposed by the licensing requirements, measured by factors such as the number of days of education and experience required, the number of exams license applicants must take, and the amount of license-related fees.

With No. 51 being the least restrictive and No. 1 being the most, Illinois at No. 39 performed better than most states for the number of occupations it licenses and the burden of its licensing requirements. California, on the other hand, topped the list as the “most broadly and onerously licensed state,” while Wyoming ranked No. 51 as the least restrictive state overall for licensing.

But the overall ranking belies Illinois’ particularly harsh restrictions on a number of seemingly arbitrary occupations.

The IJ report found significant variance among the states in both the jobs licensed and the burdens imposed on those seeking licenses, which indicates much of licensing has little to do with protecting the public from harm.

For example, Illinois requires sign language interpreters to pay a $900 fee, complete over four years of education and pass two exams to obtain a license. However, 29 states do not license this profession at all. Among the minority of states that license sign language interpreters, the average fees are $661, and the average education requirement is just under three years.

The IJ authors note that licensing burdens bear little relation to the public health and safety dangers posed by insufficiently trained or supervised professionals. The report gives the example of emergency medical technicians, or EMTs, which all 50 states and Washington, D.C., license. Although EMTs, who are first responders at accident and disaster sites, can administer oxygen, start IVs, treat wounds and perform artificial resuscitation, 73 other professions have heavier average license burdens. In Illinois, a cosmetologist must complete 350 days of educational training, but an EMT can be licensed after just 37.

Given the inconsistent and irrational treatment of occupational licenses, it is not surprising that these regimes often originate and are perpetuated for protectionist reasons.

In many cases, state lawmakers institute licensing requirements in response to lobbying by those already working in a given field, rather than because of consumers’ concerns. The report notes that licenses primarily benefit the licensed workers themselves through reduced competition, as it limits the ability of new workers to enter the field. This allows existing workers to charge higher prices for their services.

Illinois should reduce licensing burdens

While Illinois on average has less broad and less onerous licensing requirements than most other states, it should do everything possible to remove or reduce unnecessary burdens on those trying to earn a living.

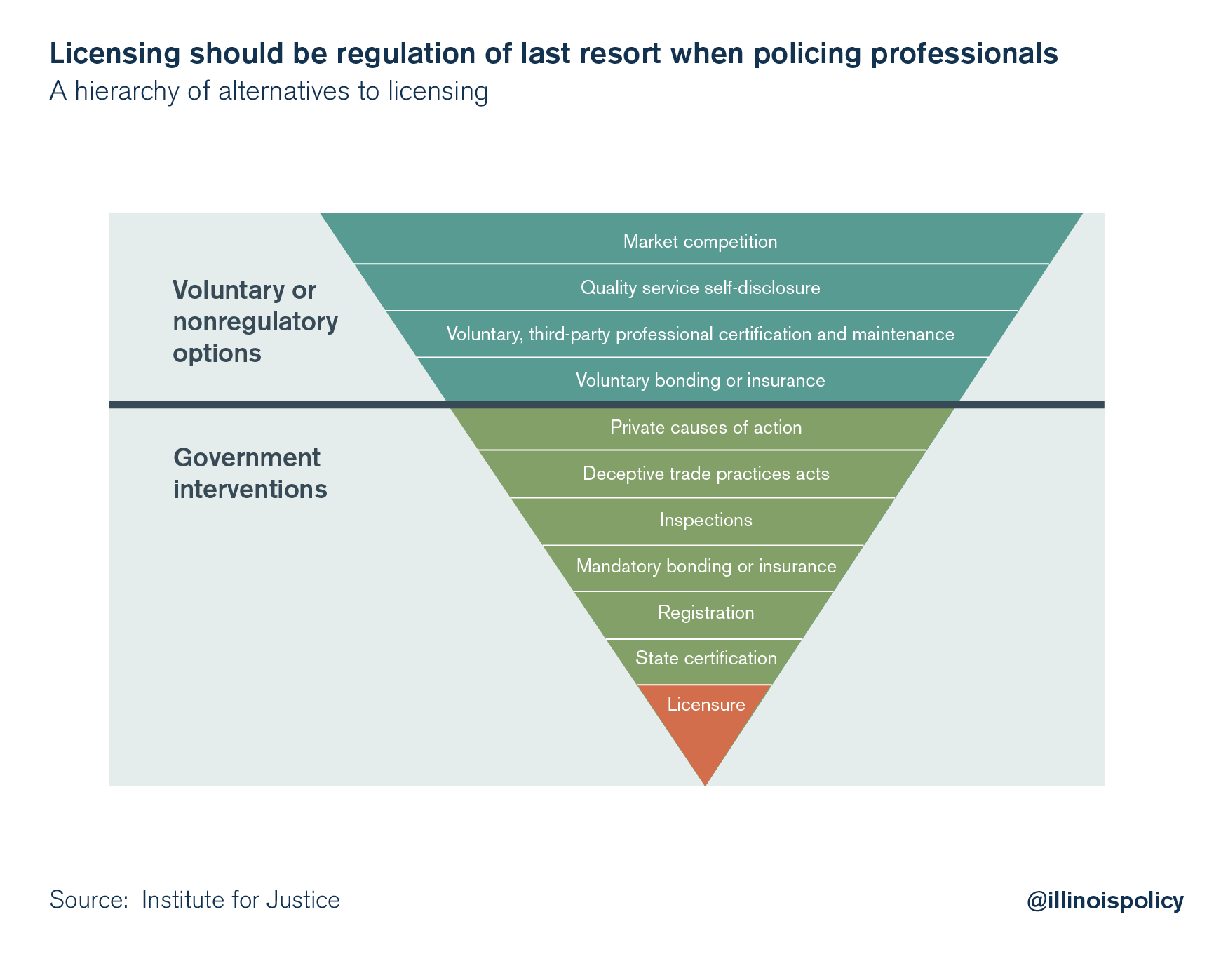

As the IJ report shows, the least intrusive way to ensure professionals are qualified to practice in their fields is through market competition. In this era of online reviews and consumer resource outlets, consumers can punish poor skills and shoddy service and reward exemplary work more effectively than ever. Other market-based ways to communicate quality and value and protect against risk include service providers sharing information about their work from third parties, voluntary professional certification and maintenance and voluntary bonding and insurance.

In cases in which voluntary, market-based mechanisms are inadequate to protect the public from real threats posed by poorly done work, the IJ authors recommend that whenever possible, policymakers intervene in ways that stop short of licensure. These options range from allowing consumer lawsuits for malpractice or defective work, to requiring inspections and insurance, to mandating that practitioners register with or become certified by the state. Among government interventions, licensure should be a last resort.

To address problems with the current licensure regime, Illinois policymakers should review each occupation the state licenses and examine whether licensure is necessary to protect the public from widespread, demonstrated harm that could occur from the unlicensed practice of the occupation. Policymakers should question whether the occupation is practiced safely without licensure in other states, too.

To reduce real harms or risks, policymakers should start with the least restrictive method, such as relying on private certifying organizations to designate competent practitioners or voluntary bonding or insurance. Only when harm cannot be mitigated by nongovernmental means should government get involved. And even in those cases, policymakers should start with the least restrictive ways and use licensure only when absolutely necessary.

Illinois lawmakers took a step in the right direction by repealing the Illinois Athlete Agents Act in 2017, which means people who wish to work as agents for athletes no longer need a license from the state to do so.

Where licensure is appropriate, policymakers should guard against “license creep,” which occurs when the boundaries of professions expand and rules apply to many practices that can be done by other, often lower-cost, professionals. Illinois made progress toward reducing license creep when Gov. Bruce Rauner signed into law an expansion of practice authority for advanced practice nurses, allowing these health care professionals to perform more tasks independent of physicians.

Illinois policymakers should also reconsider rules that keep many ex-offenders from practicing in given fields. The state took a significant step forward in this regard in 2016, when Rauner signed into law a bill to allow people with certain felony convictions to ask the state for a waiver to apply for a health care worker license. In 2016, the governor also signed a bill to allow ex-offenders to apply for licenses to work as barbers, funeral directors and roofing contractors, among other occupations. Illinois needs to continue down this path and repeal any rules that unnecessarily keep former offenders from getting the licenses they need to earn a living.

Licensure – requiring a government permission slip for someone to work in his or her chosen field – is a severe form of state-imposed quality control. Aside from the employment-quashing effects, it is often an unnecessary method for protecting the public, and is frequently poorly suited to that end.

Illinois can boost opportunity for more people by overhauling outdated and ineffective licensing restrictions.