Harvey pension crisis shows why local governments need a 401(k) option

The Harvey, Illinois, firefighters’ nearly bankrupt pension fund makes up just one part of Illinois’ combined $267 billion in state and local pension liabilities.

The pension crisis unfolding in Harvey, Illinois, is just the latest example of why it’s time for cities to move away from defined-benefit pension systems and toward 401(k)-style plans.

Politicians have proved time and again they can’t – and shouldn’t – manage worker retirements.

Cities across Illinois are dealing with their own individual police and fire pension crises. The crises they face are taking away funding for roads and local services, pushing up property taxes to among the highest in the nation, and bankrupting local cities.

There are a variety of reasons for the collapse in local pensions. Local officials have allowed benefits to grow far faster than local taxpayers can pay for them. They’ve granted perks such as sick day accumulation and unaffordable salary spikes. Politicians have treated their local pension systems as their own political slush funds. Many others have failed to contribute needed dollars to the systems. And many officials have failed to take into account changing demographics that have drained pension funding even faster than expected.

All these issues stem from local politicians’ inability to manage local public safety pensions properly.

The pension crisis in Harvey is a good example of the problems that many cities across the state are facing. The pension fund for Harvey firefighters is approaching complete insolvency after years of mismanagement by the city.

The city’s crisis was caused by benefits rising faster than local taxpayers can afford and exacerbated by local officials’ underfunding of the system.

Today, the fund has less than 30 cents for every dollar it needs on hand now to pay out future benefits.

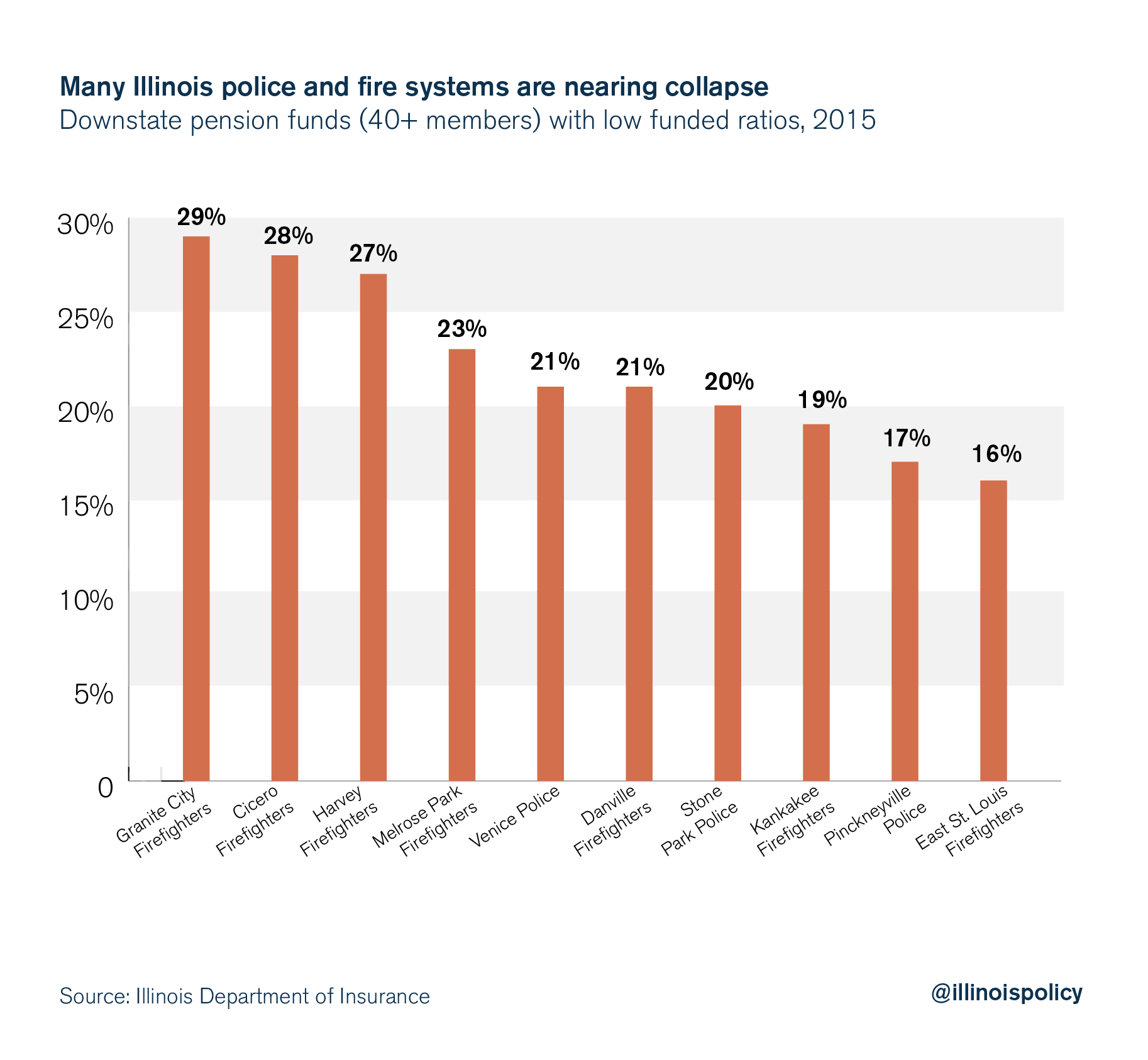

Harvey is not alone in its crisis. Over 30 percent of local police and fire pension funds have less than half the money they need on hand today to pay out future benefits. That’s despite billions of additional local tax dollars that have been collectively poured into local pensions over the past decade.

Downstate police and fire pensions are a part of Illinois’ collective $267 billion retirement crisis. And as with state pensions, the only way to begin an end to the local crisis is for cities to introduce responsible, manageable 401(k)-style plans for workers going forward.

Creating 401(k)s will stop the bleeding of local finances. But more work will have to be done to fix local communities’ massive debt, including authorizing municipal bankruptcy, reduction in benefits through collective bargaining, and changes to the Illinois Constitution.

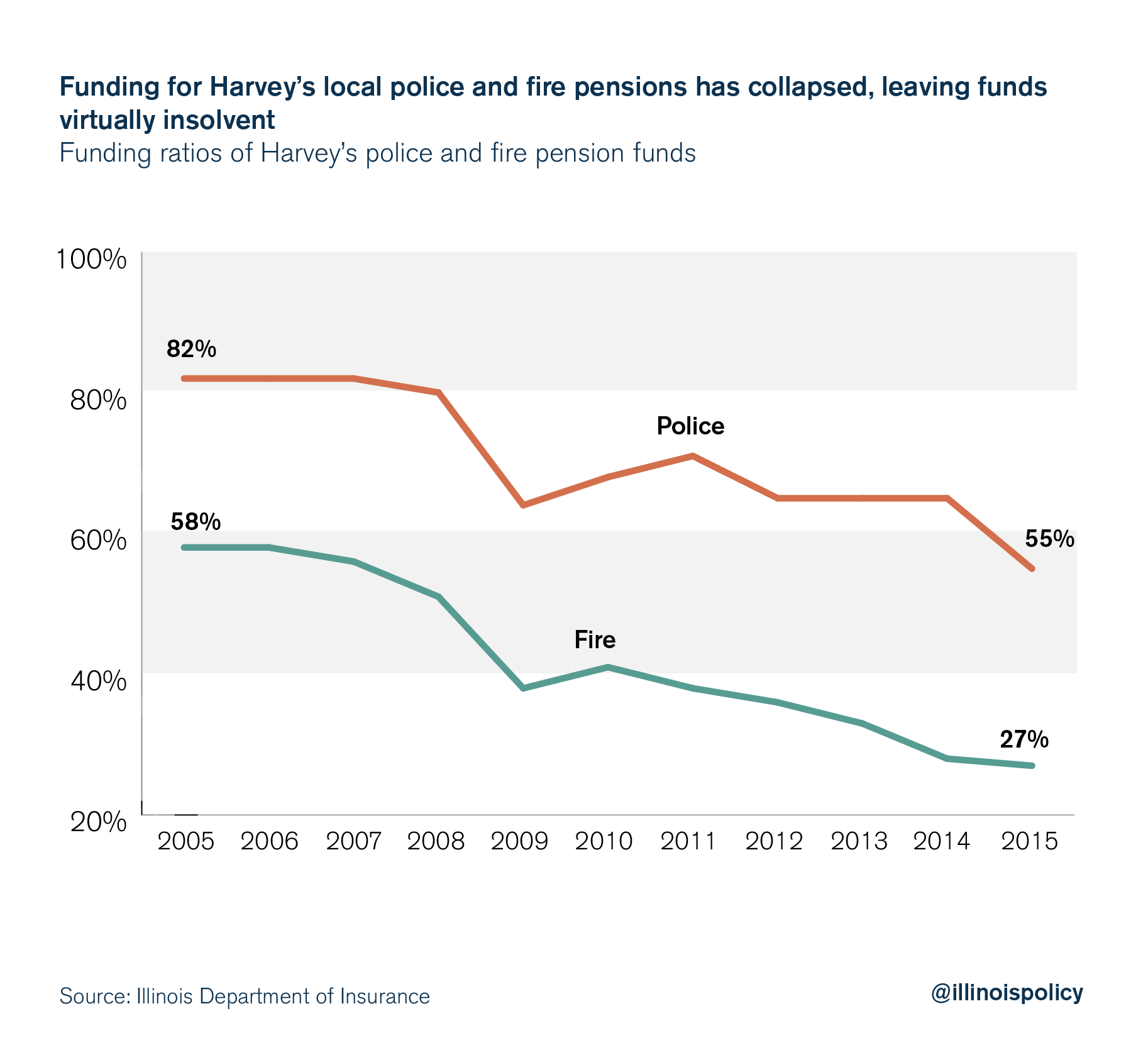

Harvey’s insolvent pension funds

A state appellate court recently ruled that Harvey’s firefighter pension fund is “on the verge of default or bankruptcy,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

The system is 27 percent funded and has more retirees enrolled than active workers. In 2015, there were 65 retirees receiving benefits, but only 47 active workers contributing to the fund. That’s only accelerated the fund’s decline into insolvency.

In fact, the appellate court found that the pension fund could run out of money completely in less than five years.

The city’s police pension fund is also in bad shape. It only has 55 percent of the money it needs on hand to pay out future benefits.

Both of Harvey’s public safety pension funds are virtually insolvent. If the funds were part of the private sector, they would have been declared bankrupt years ago.

Harvey’s funds are in such dire straits because of the city’s mismanagement. City officials allowed benefits to grow faster than taxpayers could afford and failed to pay in what was required to keep the funds healthy.

Pension benefits accumulated by the city’s firefighters – what’s owed to them in retirement – grew by nearly 25 percent between 2009 and 2015, to $43 million from $28 million. In that same period, private sector earnings for Harvey residents actually fell by more than 10 percent.

And while benefits grew and residents’ incomes fell, Harvey officials skipped making payments to the pension fund for nearly a decade. Over that period, the city contributed just 17 percent of what the fund actually needed to stay afloat.

The courts have ruled that the city now has to put money into the pension fund, which will cost struggling taxpayers in Harvey millions of additional dollars a year.

But pouring additional tax dollars into the firefighters’ pension won’t solve one of the fundamental problems with pensions: mismanagement by politicians.

The simple fact is that pension funds are unmanageable for both state and local politicians because they are unpredictable, based on assumptions that simply can’t be met and are prone to both mismanagement and corruption.

Many of Illinois’ 651 individual downstate police and fire pension funds continually fail to meet the assumed investment rates of return needed to meet their pension promises. Others have had to adjust their actuarial assumptions, further driving up costs.

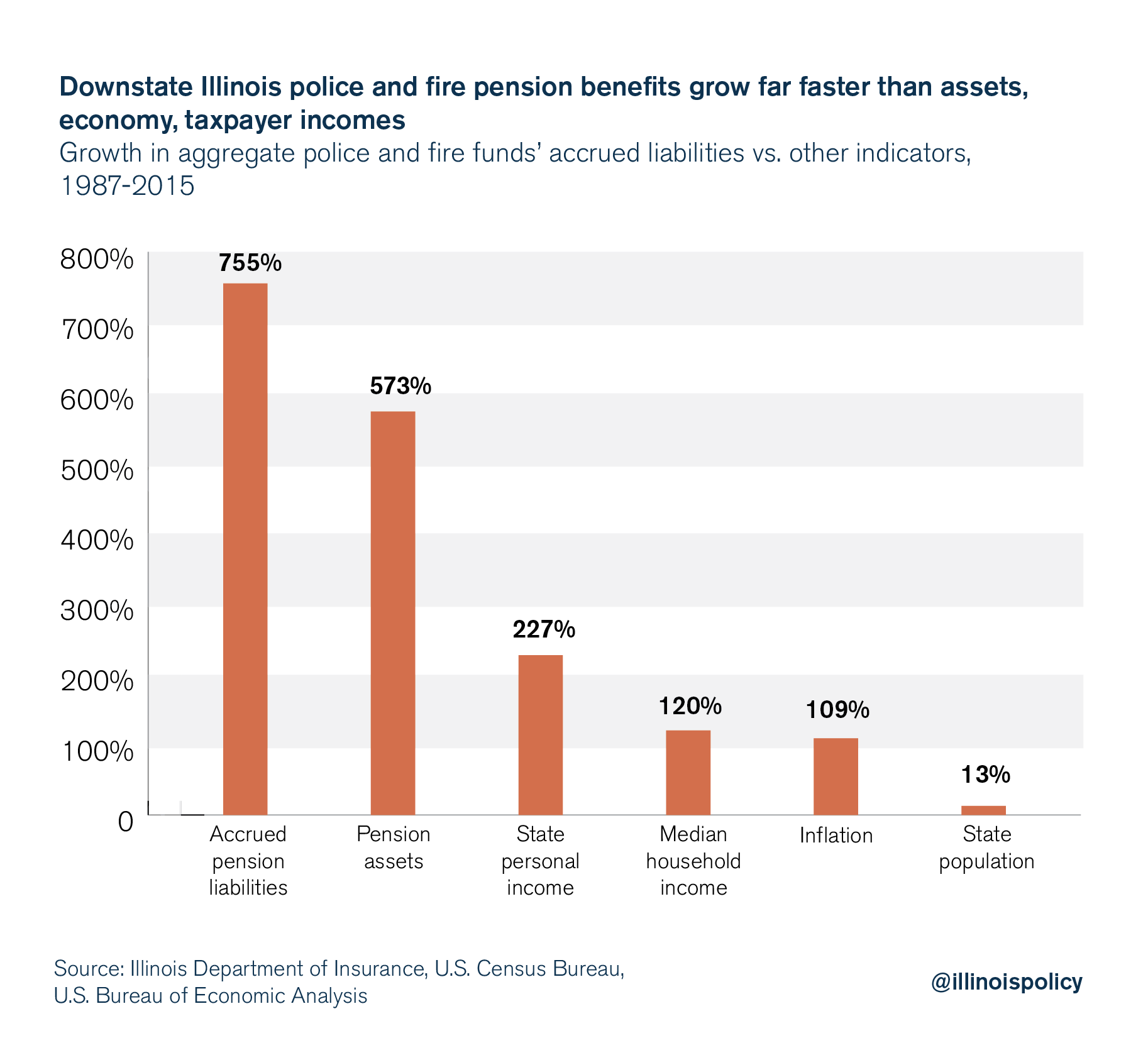

But the biggest reason downstate pensions are struggling is the rapid growth in member benefits (accrued liabilities) over the past several decades.

The assumed benefits for police and fire workers have grown by over 750 percent over the past 30 years, far faster than fund assets, the economy, inflation, the state’s population and taxpayers’ ability to pay for them.

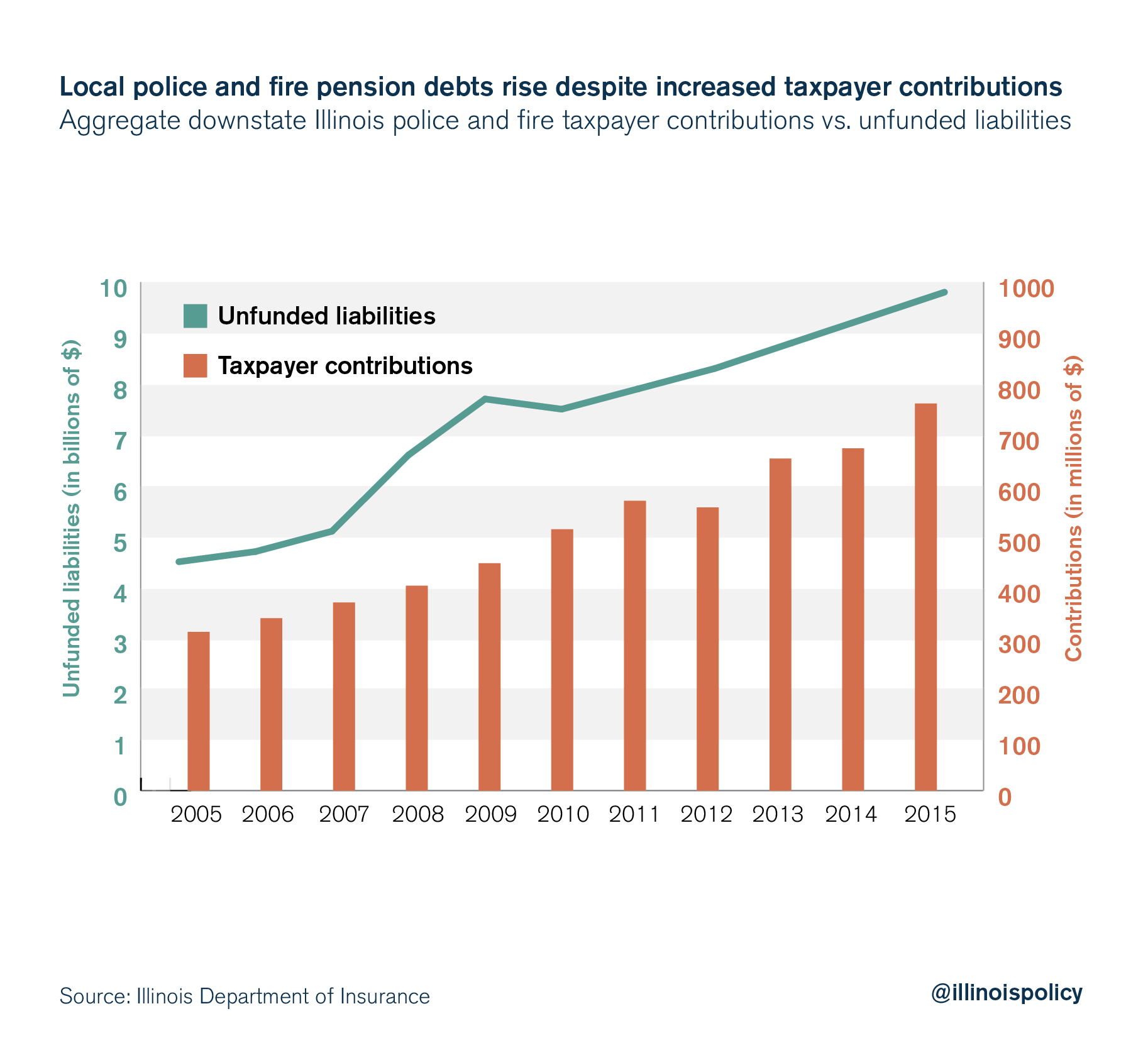

With benefits growing so rapidly, even pouring hundreds of millions of additional taxpayer dollars into local pension funds has not been enough to keep them healthy.

Despite taxpayer contributions rising by $450 million dollars over the past decade, aggregate unfunded police and fire pension debts continue to rise uncontrollably. Police and fire pension debts have more than doubled to nearly $10 billion dollars in 2015 from $4.5 billion in 2005.

Over 30 percent of downstate pension funds have less than half the money they need on hand today to pay out future benefits.

And there are over 25 pension funds that are less than 25 percent funded.

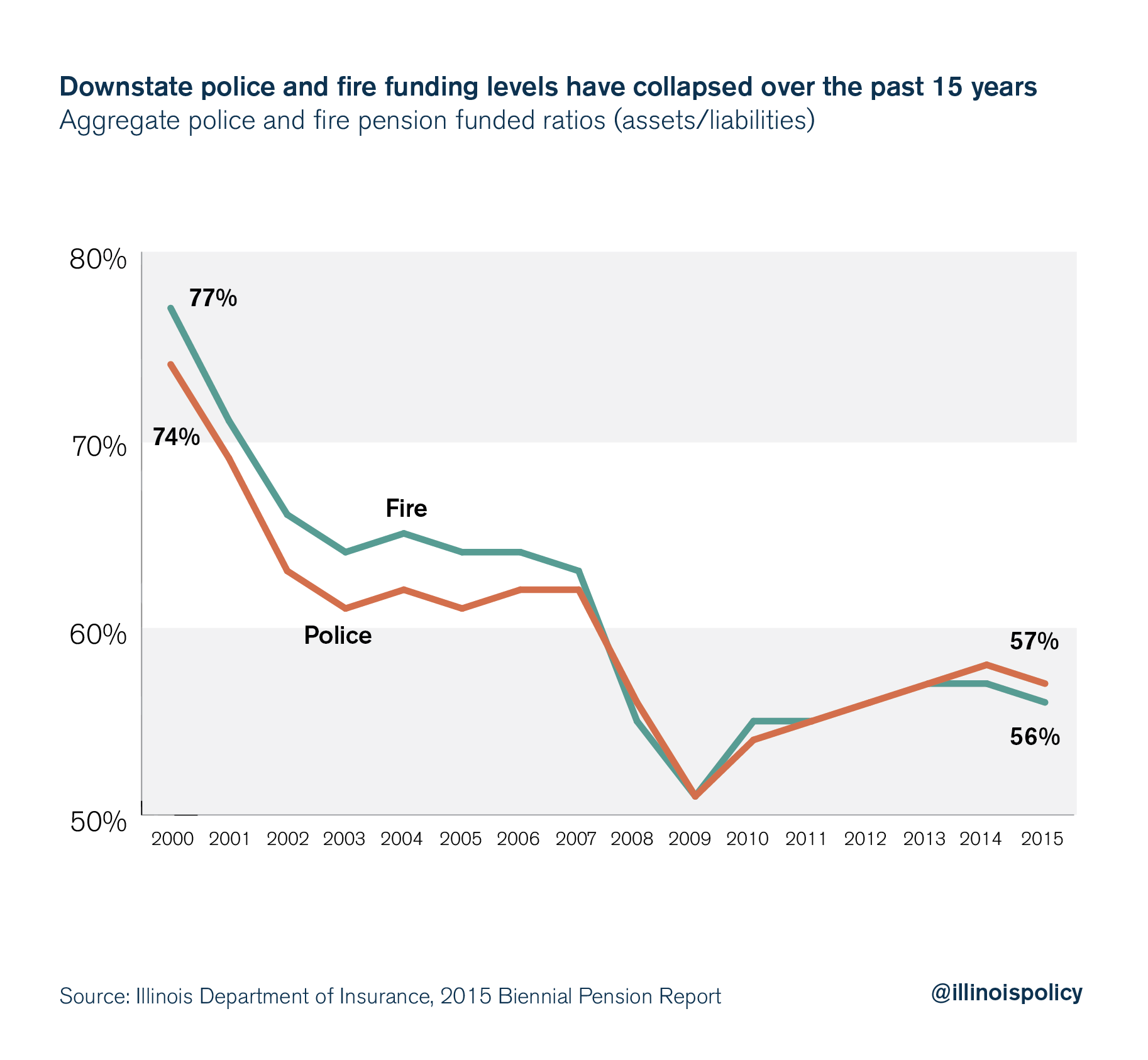

The aggregate funding ratios for Illinois’ 651 downstate police and fire pension funds have collapsed over the past 15 years. Today, both sets of funds are barely more than 55 percent funded.

The defined-contribution solution

The retirements of Illinois’ public safety workers are at risk because of the inherent failures of defined-benefit plans.

The current pension system is unfair to both public safety workers and taxpayers. Police and fire workers don’t have a secure retirement – especially workers like those in Harvey, who are close to losing their retirements altogether. Taxpayers are paying more toward a broken and bankrupt system. And those who depend on core government services are getting fewer services.

Both deserve a better system such as 401(k)-style plans.

Defined-contribution plans such as 401(k)s are far superior to pensions because they can’t be driven into the ground by politicians’ mismanagement.

Local police and firefighters who participate will control their own portable retirement accounts. And because contributions to the plan are mandatory, members won’t have to depend on IOUs from their local politicians. Both workers and the city are required to contribute a percentage of salary each and every paycheck.

Illinois politicians can begin an end to the downstate pension crisis by allowing local municipalities to create 401(k)-style plans for new workers going forward.

Those new plans can be modeled on the 401(k)-style plan used by over 20,000 members of the State Universities Retirement System.

New 401(k)-style plans won’t solve Illinois cities’ pension debt problem overnight. But they will stop the the creation of more debt.

Dealing with local communities’ already-accumulated debt will require additional reforms, from allowing municipal bankruptcy, to unions agreeing to pension changes through collective bargaining, to amending the pension protection clause in the Illinois Constitution.

But in the meantime, moving new workers to 401(k)s will at least slow down and eventually stop city pension debt from growing.

And most importantly, 401(k) plans won’t trap public safety workers in funds mismanaged by local politicians.