Flying blind: Illinois’ revenue estimates and the basics of bad budgeting

Lawmakers can’t balance the budget if they don’t know how much they have to spend.

Illinois hasn’t had a truly balanced budget for more than 15 years. And state spending has far outpaced growth in residents’ incomes. These are two reasons why Illinois is in desperate need of a spending cap that ensures residents are getting a state government they can afford.

But there’s another key reason Illinoisans need a spending cap: lawmakers can’t reliably figure out how much money they have to spend each year, with state officials consistently producing revenue projections that don’t match one another or the actual amount of revenue the state ends up generating.

This level of uncertainty – and the opportunity for other policy considerations to enter the basic budgeting process – has lead to busted state budgets year after year.

Revenue estimates and Illinois’ “balanced budget” requirement

The Illinois Constitution already requires a balanced budget. By law, the General Assembly is not allowed to appropriate more money than is estimated to be available for the budget year. Still, the state of Illinois has not had a truly balanced budget since at least 2001. A report from Thomas Walstrum at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago found that combined state and local spending in Illinois has been higher than combined revenues since the late 1980s. In other words, Illinois governments have been piling on debt for decades.

To understand why the constitutional balanced budget requirement is ineffective, it’s important to understand how the budget process works in Illinois.

State law currently requires two separate entities to estimate revenue for the coming year. The executive estimate comes from the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, or GOMB, and is used by the governor in his annual budget proposal. A second estimate comes from the legislative Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, or COGFA. Unfortunately, these two estimates rarely match either each other or the amount of revenue that actually ends up coming in.

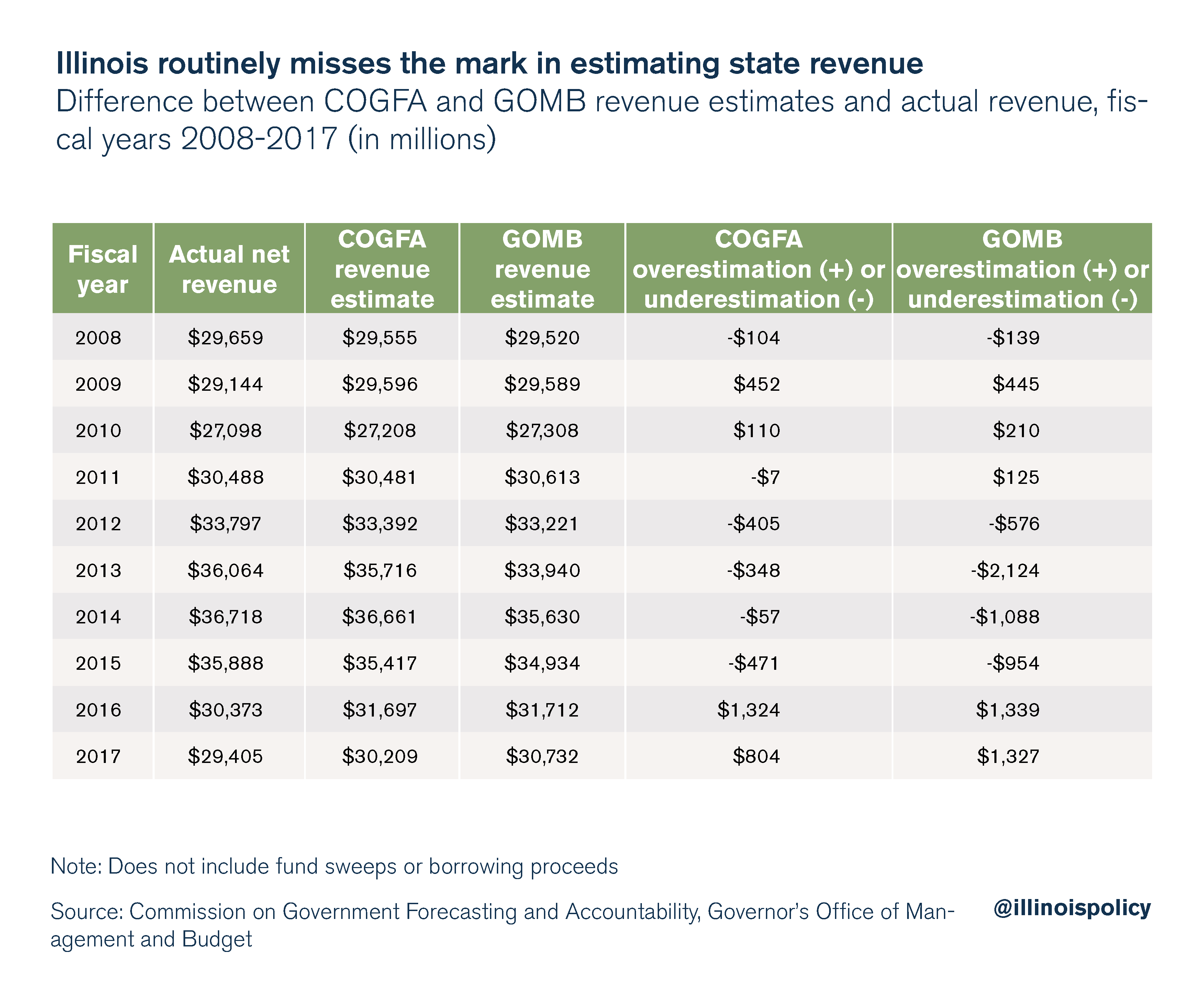

Based on the standard for revenue projections used by the National Association of State Budget Officers – estimates within 0.5 percent of actual revenues are considered “on target” – COGFA revenue estimates have been accurate in only four of the last 10 years. GOMB estimates have been on target in only two of the last 10 years.

In fiscal year 2016, COGFA and GOMB both overestimated the amount of money the state would have to spend by more than $1.3 billion, or nearly 4.5 percent of actual revenue. For the median family in Illinois with two kids, making around $73,700 according to the U.S. Census Bureau, this would be equivalent to thinking they have $3,300 more than they actually do for their annual budget. Illinois families could not get by with that kind of budget uncertainty, but that’s the way policymakers have been doing business in Illinois for decades.

In fact, the General Assembly has not even bothered to adopt a revenue estimate since 2014, even though Illinois law requires them to do so. The General Assembly’s estimate is usually based on the GOMB estimate, the COGFA estimate or an average of the two. The fact that lawmakers have been spending money without figuring out how much they have beforehand helps explain why the fiscal year 2018 budget was initially $1.7 billion out of balance, even after a record $5 billion tax increase.

Both COGFA and GOMB are likely doing their best. The problem is that revenue estimation relies on a complex set of unpredictable economic variables. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers, 33 states underestimated revenue in 2017, 13 overestimated revenue and only four were reasonably on target.

Motivated math

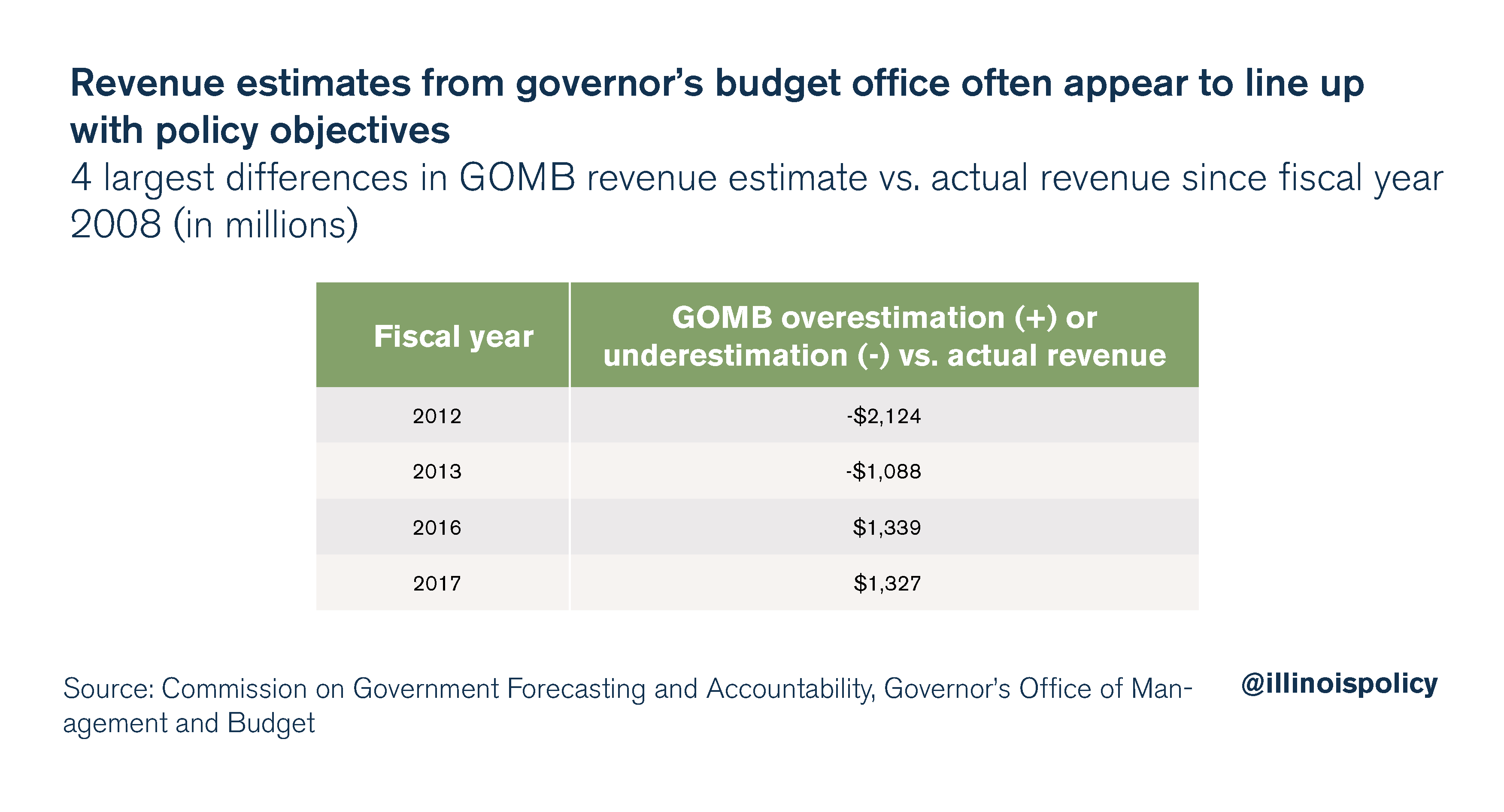

In a perfect world, estimating revenues for the coming year would be a purely mathematical process free from politics. Both GOMB and COGFA use the same econometric firms when developing their forecasts. The reason the final estimates differ is due to the way these offices choose to analyze the data. Differences may also be grounded in other policy considerations, a possibility which looks likely when examining the largest overestimations and underestimations over the last 10 years.

For his 2013 budget proposal, while advocating for extending or making permanent the 2011 income tax increase, former Gov. Pat Quinn went so far as to propose two budgets to the General Assembly: a “recommended” budget including an extension of the tax increase and a “not recommended” budget that purported to show the deep cuts that would be necessary if the tax increase were allowed to expire.

In other words, an underestimation of revenue from his budget office would suit Quinn’s policy goals by making an extension of the tax increase seem necessary. Indeed, his fiscal year 2012 and 2013 revenue estimates were short by about $2 billion and $1 billion, respectively.[1]

In 2016, newly elected Gov. Bruce Rauner was trying to balance the state budget without advocating for tax increases. The more revenue the state was expected to bring in, the easier this task would be. Sure enough, GOMB estimates for fiscal year 2016 and 2017 overestimated revenue by about $1.3 billion each.

Only the analysts and decision-makers within the governor’s office can say for sure what their motivations were for using different assumptions in their revenue forecasting, but from the outside looking in, the estimates seem to conveniently line up with each governor’s policy goals.

Certainty, security for taxpayers

Illinoisans deserve balanced budgets. Every year, lawmakers spend more than they take in, which means another round of borrowing or tax increases. But lawmakers cannot be expected to reliably balance the budget if they cannot predict how much money they have to spend.

Thankfully, a constitutional spending cap would make the math significantly easier for them. Under the spending cap constitutional amendments currently enjoying bipartisan support in the General Assembly, lawmakers would simply grow spending each year at the average rate of per capita growth in Illinois’ economy over the past 10 years, giving them a definite dollar amount to spend each year.

The budget certainty this spending cap would provide would help put Illinois back on the path to financial stability while protecting taxpayers.

[1] For most fiscal years, both GOMB estimates and COGFA estimates are taken from the COGFA annual budget summary to ensure an apples-to-apples comparison. The fiscal year 2012 and fiscal year 2013 GOMB estimates are instead taken directly from the GOMB proposed operating budgets, because COGFA did not include comparisons for these years. COGFA typically makes adjustments to GOMB estimates for comparison. Differences in the treatment of certain categories may account for some of the difference from actual revenues.