Damage from Edgar ramp obscured by dotcom boom

Former Gov. Jim Edgar’s pension compromise with House Speaker Mike Madigan in the 1990s set the state’s pension funds down an unsustainable road.

Former Illinois Gov. Jim Edgar likes to take credit for improving the state’s pension finances during his tenure from 1991 to 1999. The 1994 pension reform compromise he reached with Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan, known as the Edgar ramp, required the state to make annual appropriations to the pension funds for the first time. Edgar has consistently called for Gov. Bruce Rauner to similarly “compromise” on major reforms, citing the fiscal responsibility of his own deals.

However, Edgar can’t claim the mantle of “fiscal responsibility.” Not only was his pension ramp financially irresponsible at its core, but Edgar’s broader handling of pensions during his time in office laid the foundation for Illinois’ current financial and public pension crises.

Edgar has avoided criticism because the impact of his poor pension policies was hidden by the spectacular market returns of the dot-com boom and accounting rules that artificially improved the health of the pension funds.

- Edgar agreed to an irresponsible funding ramp

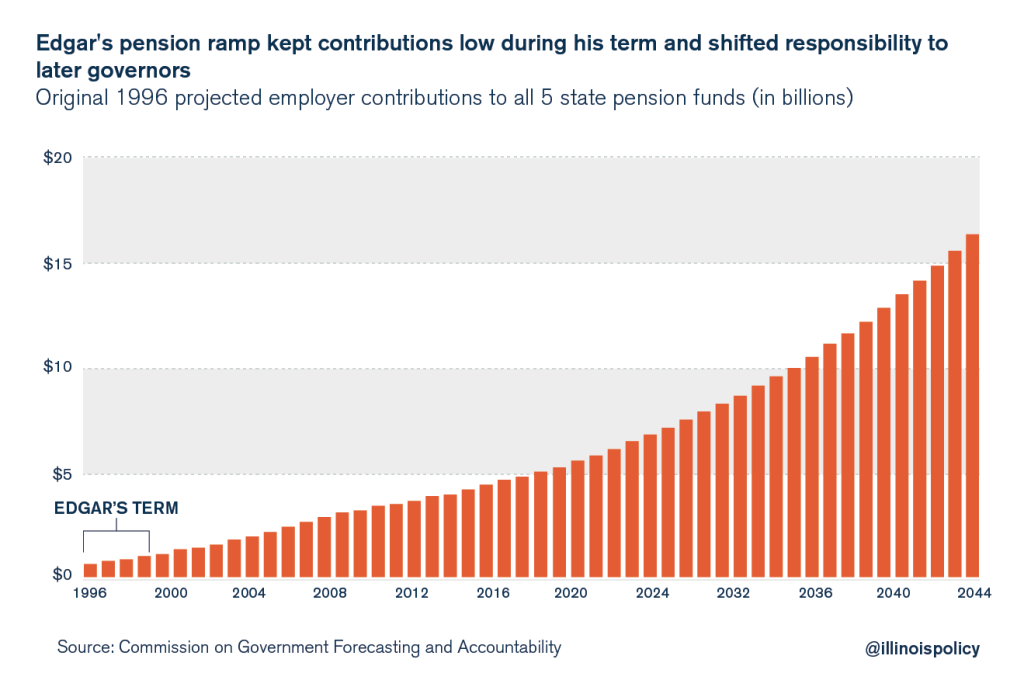

As part of the Edgar ramp compromise, Edgar agreed to a 50-year repayment schedule that kept the state’s pension contributions artificially low in the first 15 years, all while pushing the state’s pension obligations far off into the future. That kicked the pension-funding can down the road for future governors.

Some might argue the ramp was the best bipartisan and politically tenable deal that could have been made at the time, but that argument misses the point. The ramp was not real reform. The fact that it was created through compromise is irrelevant.

- Edgar avoided structural reforms to the pension funds, grew benefits

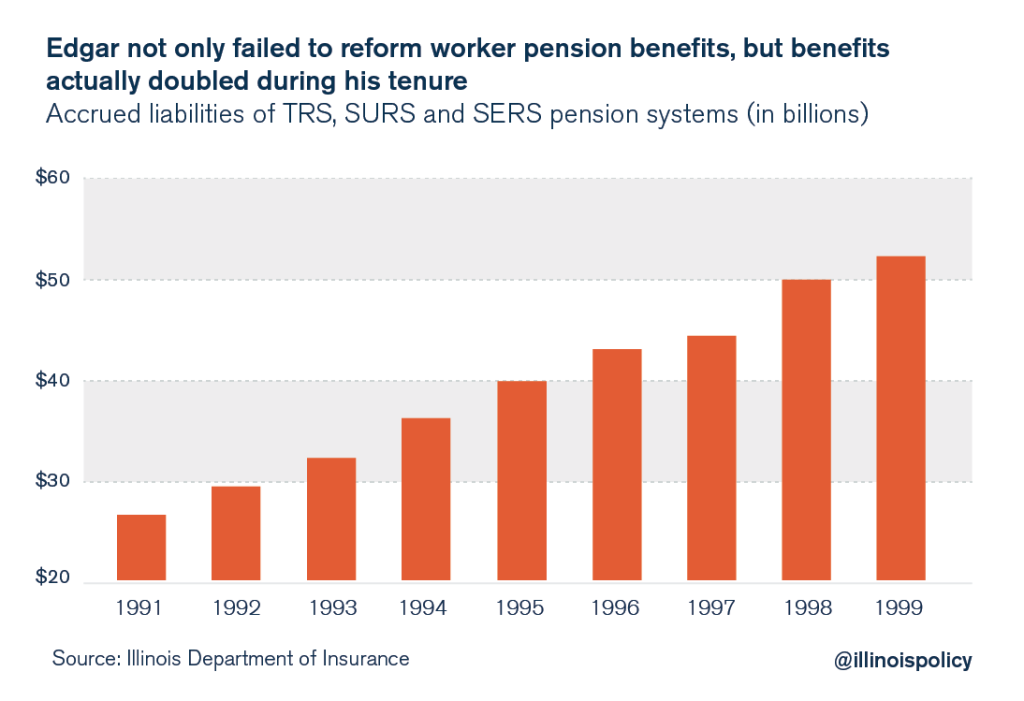

Edgar didn’t implement any structural reforms to decelerate the funds’ irresponsibly high growth in promised pension benefits. During Edgar’s term, promised pension benefits grew at the unsustainable rate of 9 percent annually.

From 1991 to 1999, promised pension benefits doubled to $53 billion from just under $27 billion, growing faster than state revenues, inflation and taxpayers’ ability to pay for them.

In fact, rather than reform benefits, Edgar increased them. In 1997, the 90th General Assembly passed, and Edgar signed, a retirement formula increase for members of the State Employees’ Retirement System, or SERS, and Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, growing those workers’ promised benefits going forward.

Edgar’s agreed-upon funding ramp and lack of comprehensive benefit reforms accelerated Illinois’ current pension crisis.

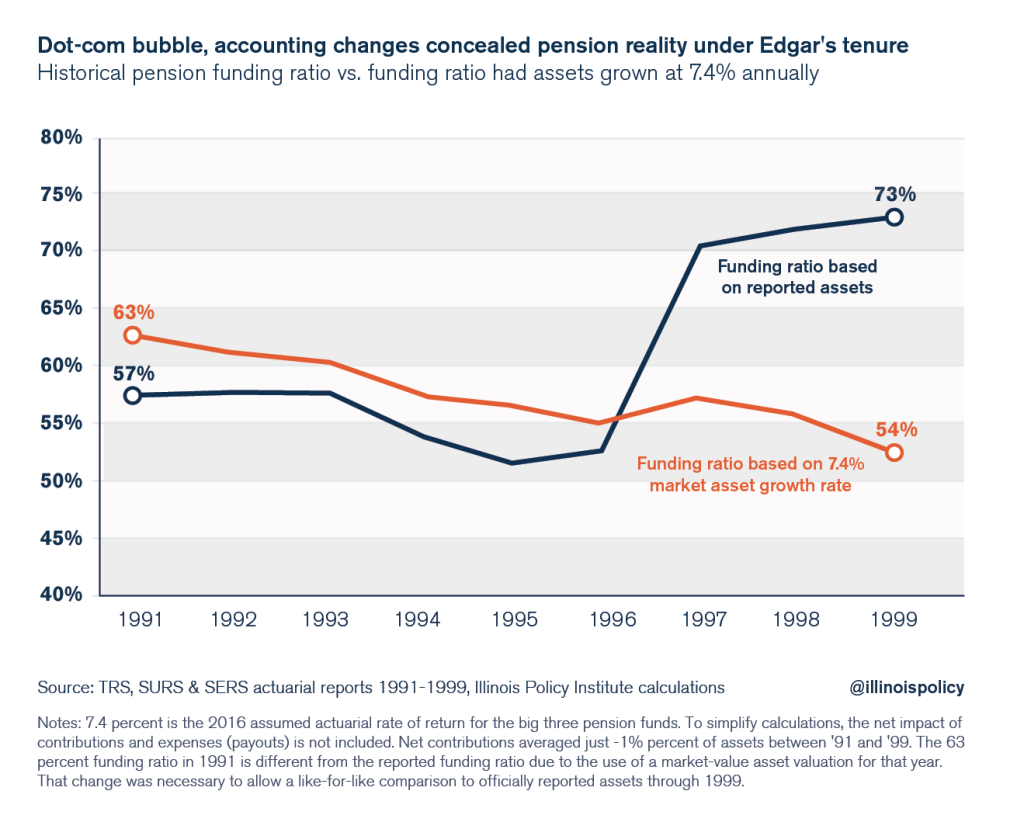

But spectacular stock market returns and new accounting rules – unique to Edgar’s tenure – hid the effects of Edgar’s policies during his time in office. Indeed, the funding levels for Illinois state pension plans rose to 73 percent by the time Edgar left office, compared to just 57 percent during his first year in office.

- Under Edgar, spectacular stock market returns hid Illinois’ pension issues

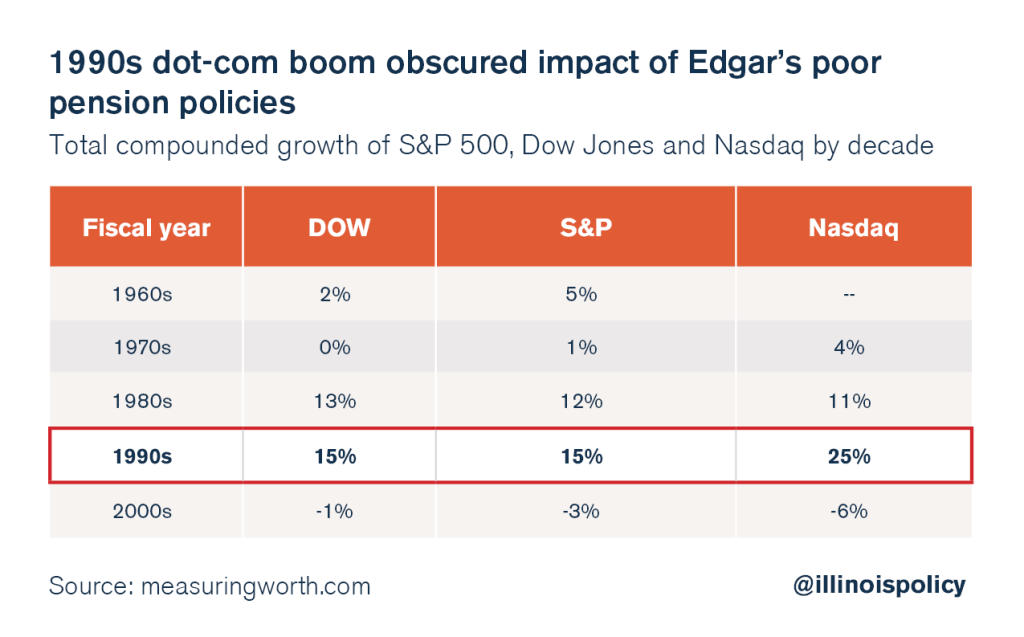

The stock market experienced massive gains during the 1990s, in large part due to the dot-com boom. The Dow Jones industrial average, Standard & Poor’s 500 index and the Nasdaq composite all averaged returns in excess of what they had achieved in previous decades – and were likely to achieve in the future.

The state’s big three pension funds – teachers, university workers and state employees – took advantage of that market growth. Combined, the funds’ investments experienced an average annual growth of 12 percent during Edgar’s tenure.

In contrast, the pension funds grew just 3 percent annually from 2000 to 2009, far lower than the previous decade and far less than the 7.4 percent annual return the funds currently assume as part of their yearly actuarial calculations.

Edgar was lucky to preside over a boom period and acted as if it would continue forever. The state’s reported pension funding levels under Edgar would have been far lower if stock market returns had been normal.

If pension assets under Edgar had grown at just 7.4 percent annually – the weighted actuarially assumed rate of return for the state pension funds in 2016 (itself an unrealistically high assumption) – the pension funds under Edgar would have been just 54 percent funded in 1999, not 73 percent.

Notes: 7.4 percent is the 2016 assumed actuarial rate of return for the big three pension funds. To simplify calculations, the net impact of contributions and expenses (payouts) is not included. Net contributions averaged just -1% percent of assets between ’91 and ’99. The 63 percent funding ratio in 1991 is different from the reported funding ratio due to the use of a market-value asset valuation for that year. That change was necessary to allow a like-for-like comparison to officially-reported assets through 1999.

- Accounting changes improved the pension funds’ health

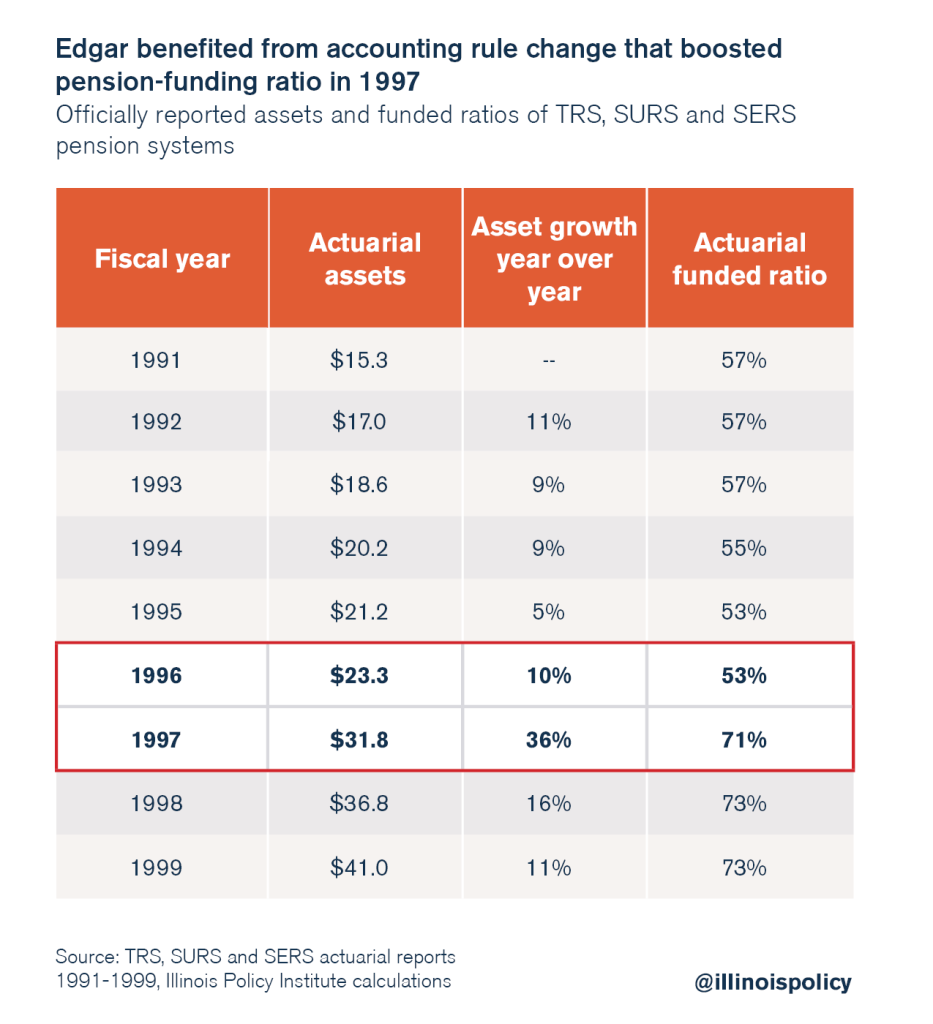

Despite the run-up in the stock market, its impact on the pension funds’ assets was not revealed until 1997.

Prior to 1997, the funds’ higher-than-usual investment returns weren’t fully reflected in the pension funds’ finances because assets were reported “at cost” – not at full market value. In 1997, however, accounting rules changed, and the pension funds began to report their assets at market value.

This change in accounting rules immediately boosted the funds’ reported assets by over $8 billion and increased the pension funding ratio by over 17 percent, to 71 percent funded in 1997 from 53 percent funded in 1996.

Illinois needs real pension reform going forward

It’s disingenuous for Edgar to claim any credit for improving Illinois’ pension systems. Not only did he set the precedent of passing the buck under the guise of reform, but he also grew promised pension benefits during his term.

Edgar, and other politicians like him, need to stop criticizing current reform efforts and focus on promoting real solutions to Illinois’ pension crisis. Any “compromise” solution like the Edgar ramp will only make the crisis worse.

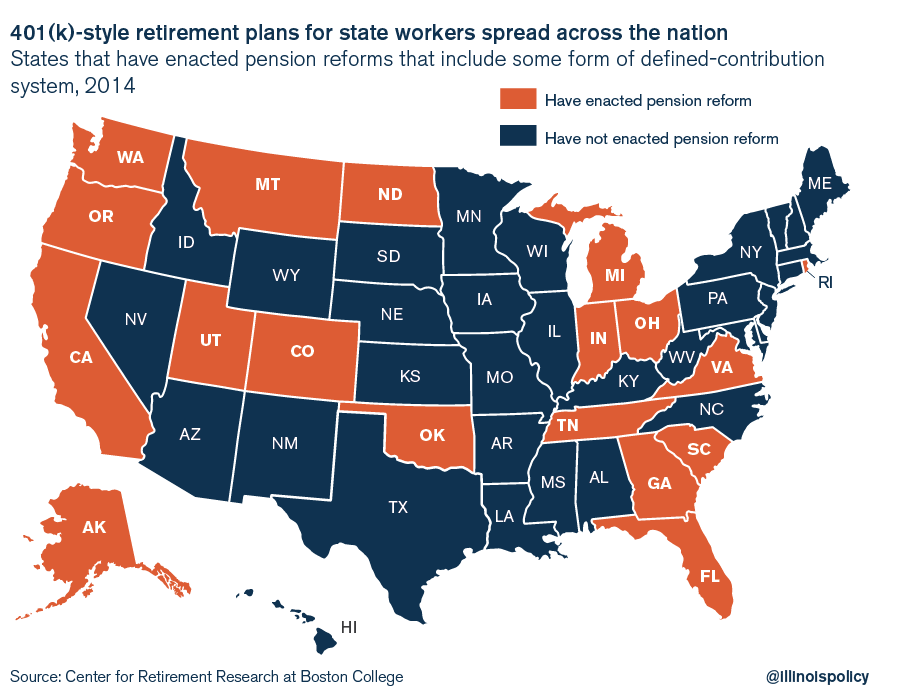

Instead, Illinois should follow the lead of the private sector and many states by ending its unmanageable and nearly insolvent defined-benefit retirement plans. Nearly 85 percent of private-sector companies now have defined contribution plans, and states ranging from Oklahoma to Rhode Island have initiated some form of 401(k)-style reform.

Illinois can start by moving new government workers to 401(k)-style plans and giving existing workers the option to have their own self-managed accounts. That, in addition to a constitutional amendment allowing Illinois to reform current workers’ unearned pension benefits going forward, would be a crucial step toward fixing Illinois’ perennial pension crisis.

Edgar should push for such comprehensive reforms rather than call for compromises that don’t solve the fundamental problems Illinois pensions face.