Prohibition, prostitution and Chicago’s mini-fiefdoms

A principle once invoked to shake down speakeasies is now used to pick winners and losers in a city desperate for opportunity.

When Mukesh “Mike” Sharma wanted to open up an upscale beer and wine shop in Chicago’s University Village neighborhood, he was told the store’s name – “Mike’s Wine and Spirits” – must be changed to “Michael’s Wine and Spirits.” This name was “classier,” said Kathy Catrambone, executive director of the University Village Association.

28th Ward Alderman Jason C. Ervin presented Mike with this condition – among others, such as price controls and hours restrictions designed to protect a liquor store owned by a village board member – before giving his blessing to the zoning board. Mike was allowed to open up shop in June 2014 after a yearlong wait.

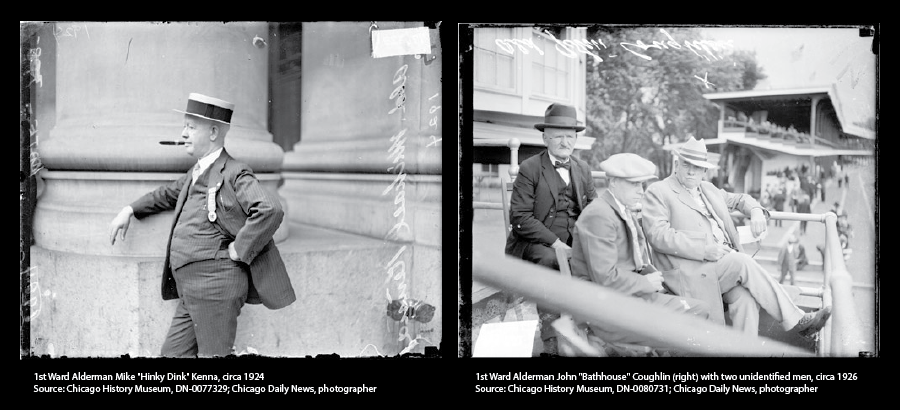

If this grimy political process is reminiscent of a mobster movie, that’s because its practice has persisted from the heyday of corrupt Chicago politics at the turn of the 20th century through Al Capone’s bootlegger era and beyond. The city’s aldermanic history even includes nicknames fit for Mafiosi: Edward “Fast Eddie” Vrdolyak, John “Bathhouse” Coughlin, Mike “Hinky Dink” Kenna and Johnny “Da Pow” Powers.

The same custom used to keep booze and patronage flowing during Prohibition, for instance, still persists today, leaving Chicagoans to reckon with an archaic political process that breeds corruption, officiousness and a dystopian business climate. That custom is referred to as “aldermanic privilege,” and it grants Chicago aldermen a level of autocratic control not seen in any other American city.

“Aldermanic privilege” is far from a common term, but think of it as a division of powers. Chicago is divided into 50 political wards, each with an elected alderman who sits on City Council, and the “privilege” comes from a simple understanding among the 50 officials: each is tacitly granted power to block or initiate any policies concerning their ward. This convention is rarely violated.

An alderman’s privileged power is most evident in near-total control of their ward’s zoning process. One may find countless Mukesh Sharmas in the annals of Chicago history for this reason.

Thus, in Chicago, a great deal of discretion has been granted to political actors infamous for corruption over the last century. In the past 40 years alone, 33 of some 200 Chicago aldermen have been convicted of federal crimes, such as bribery, extortion, embezzlement, conspiracy, mail fraud and income-tax evasion, according to 2015’s good-government masterwork, “Corrupt Illinois: Patronage, Cronyism and Criminality.”

Co-written by University of Illinois at Chicago political scientist Dick Simpson and researcher Thomas Gradel, the book details the exploits of some of Chicago’s most crooked politicians. Take the case of John “Bathhouse” Coughlin and Mike “Hinky Dink” Kenna, 1st Ward aldermen who held their respective offices from the 1890s until the 1940s (at the time, each ward had two elected aldermen):

“As [Kenna and Coughlin] were re-elected for decades and delivered the vote for party candidates, they came to control police, zoning, prostitution, and gambling in the city’s Levee District along the Chicago River for decades. Along the way they enriched themselves and their allies. They employed extortion, personal favors and voting fraud to stay in power … getting out the vote on election day involved saloon patrons being given a free lunch and beer to vote multiple times in different precincts.”

Simpson and Gradel regard aldermanic privilege as one root cause of Chicago corruption, writing: “As long as aldermen have the political clout to control zoning, licenses, permits, property-tax reductions, city contracts and patronage jobs, corruption will continue to send aldermen to prison.”

The privilege that formerly allowed for vote-buying schemes and saloon shakedowns now manifests itself as crony meddling in small-business affairs – from liquor licenses to sidewalk-café permits to signage to the right to exist at all. This is to the detriment of entrepreneurs who are ignorant of the game, or refuse to play.

Elizabeth Milnikel Kregor, director of the Institute for Justice Clinic on Entrepreneurship at the University of Chicago, has described the effects of concentrated power among aldermen on small businesses. One of her clients wanted to open up a day care in 2010 but was told by a local alderman that the area had enough already.

“She has held this building and paid property taxes for over a year now, [but] she hasn’t even been allowed to start building it up as a day care,” Kregor said. “Meanwhile this block has yet another empty building sitting there.”

The problem at hand could not be more evident: Aldermanic privilege – a political custom predating the Great Chicago Fire – is getting in the way of residents being able to build a better future for the city. And while the origins of the political-cultural problem of aldermanic privilege are complex, solutions are within reach.

Part of what invites aldermanic interference is a lengthy and costly startup process for small businesses. Vox’s Matthew Yglesias described starting a professional-services business in Chicago as a “dystopian nightmare.” It comes as no surprise then that Chicago’s rate of entrepreneurship is the second-lowest among the country’s 15 largest metropolitan areas.

Streamlining the startup process would narrow the window of opportunity for intrusive politics. The same goes for business regulation in general. While perhaps well intentioned, Chicago’s zoning and permitting restrictions too often serve only to restrict those who aren’t cunning enough to make good with the local alderman.

At the very least, the arbitrary regulatory power wielded on a case-by-case basis by Chicago aldermen must be eliminated. They have proven incapable of applying it fairly and consistently.

Along with separating political elements from business creation, the city inspector general’s office should be given increased authority over aldermen and their staff. When the inspector general position was created in 1989, aldermen exempted themselves from its scrutiny, opting instead (20 years later) to create a legislative inspector general’s office to provide aldermanic oversight. Legislative Inspector General Faisal Khan sued the city last year after his office was underfunded.

Aldermanic privilege stands as a costly monument to Chicago’s historically rapacious political culture, and has done little more than to bend the histories of neighborhoods toward the whims of the political elite. Regulatory reforms and better oversight are simple steps toward razing it.