Cook County’s budget problems stem from massive growth in payrolls

The average salary for Cook County workers has far outpaced that of the typical Cook County household since 2001, and that’s contributed to the county’s fiscal ills.

In the wake of the sweetened beverage tax repeal, Cook County is facing yet another budget gap. And Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle is placing the burden of filling this gap on county commissioners.

Preckwinkle has defended her sweetened beverage tax by claiming she’s shrunk the workforce and closed budget gaps.

“I’ve often heard others say there’s still a significant amount of fat to be cut. But to those people,” Preckwinkle said in a press release. “I remind you we already have shrunk our workforce by more than 10 percent, closed budget gaps of $1.8 billion and reduced our indebtedness by 11 percent.”

But when examining the county budget, it’s clear that the fault for the gap lies not in the repeal of the sweetened beverage tax. Contrary to Preckwinkle’s claims, it lies with years of irresponsible budgeting and growth in payrolls.

Cook County payroll boom

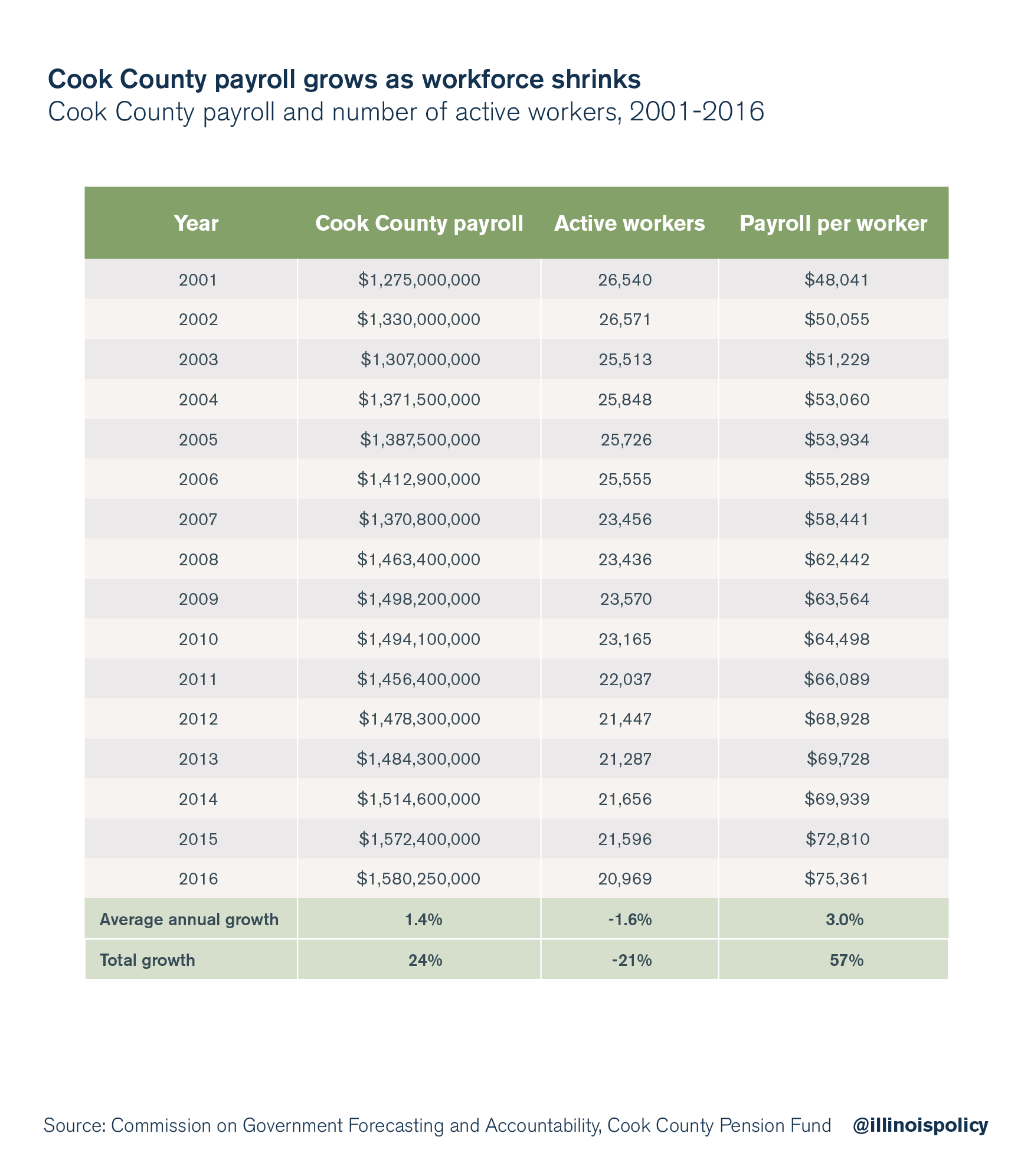

Preckwinkle is correct in saying that the county employs fewer active workers than in previous years. But those workers who remain have seen such high raises that total payroll costs have actually increased.

Cook County government’s payroll growth since 2001 has far outpaced that of the average Cook County household. And that growth has cost taxpayers dearly.

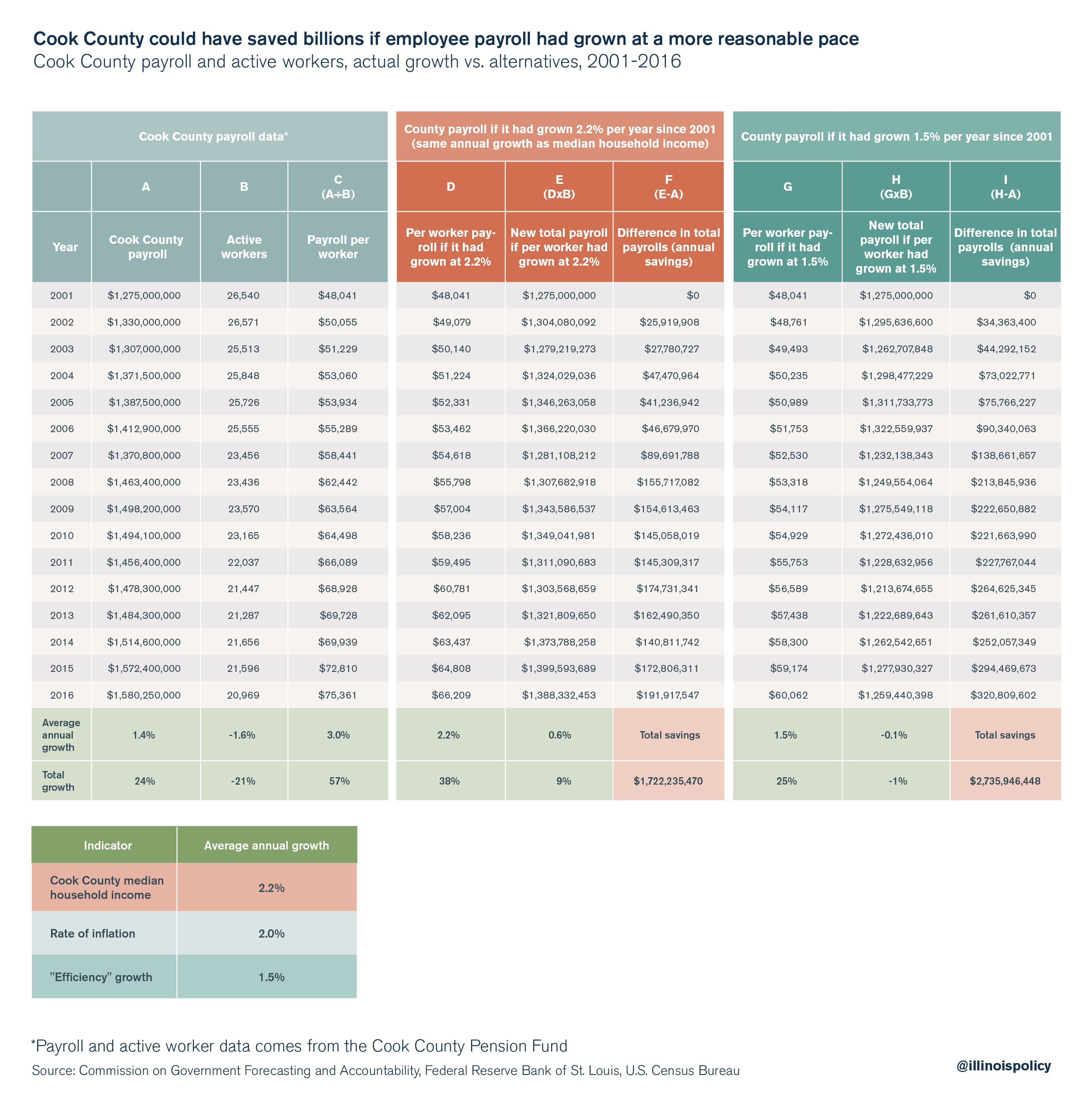

The average salary of Cook County workers – the total payroll divided by the number of active workers – has increased 57 percent since 2001, to $75,361 from $48,041. This equates to annual average growth of 3 percent.

Meanwhile, the Cook County median household income has grown by an average of only 2.2 percent per year over the same time. That means the average Cook County worker salary grew 1.5 times faster than the income of the typical household.

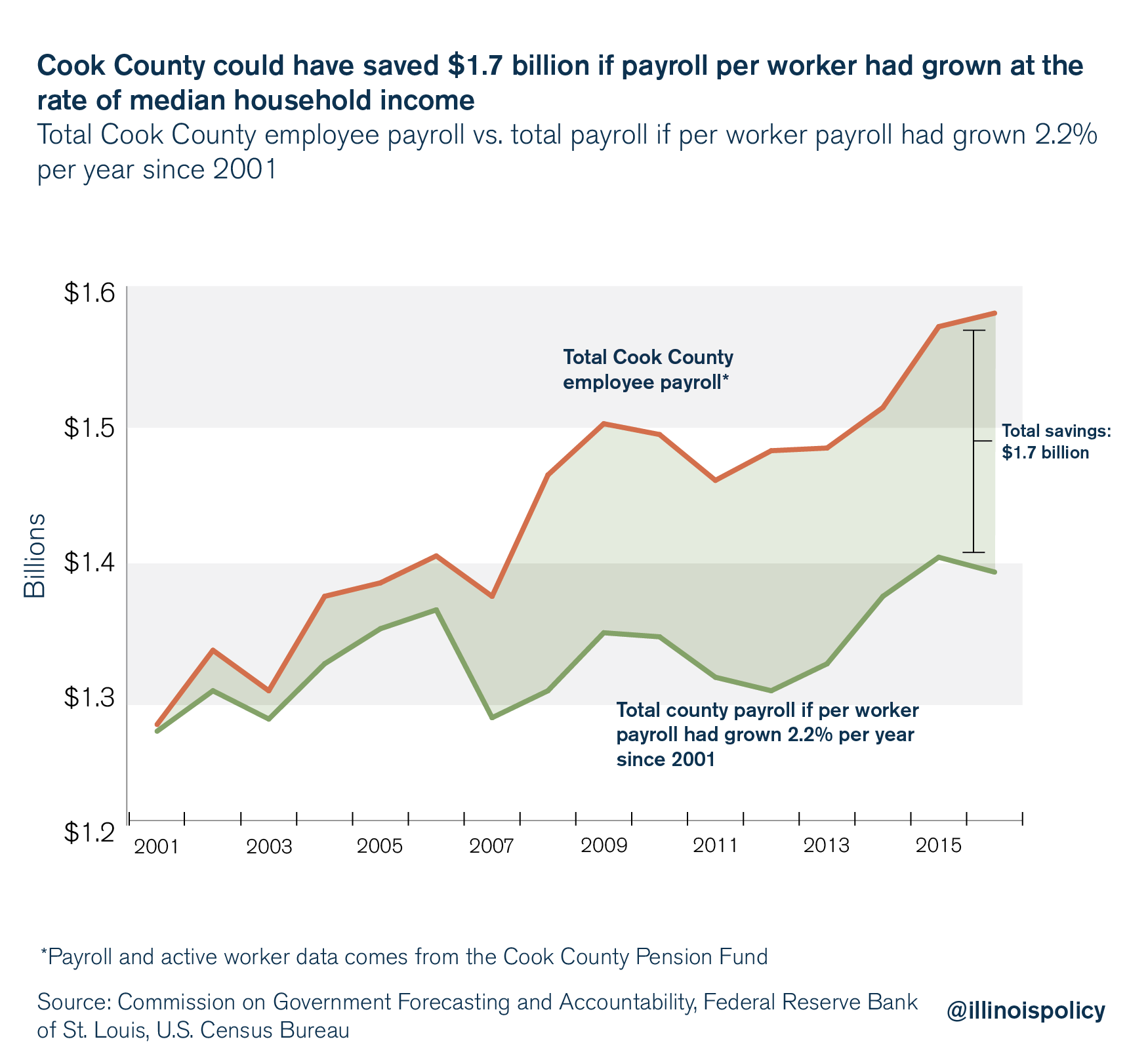

If county payroll growth had simply kept in line with the growth in income for the typical household, the county would have saved nearly $192 million in 2016; nearly the amount needed to cover the anticipated revenues from the sweetened beverage tax.

And if the county had tied payroll growth to growth in the median household income from 2001 to 2016, it would have earned savings of $1.7 billion.

Taxpayers have been asked to tighten their belts to help bail out inefficient government. The least government can do is respond in kind with similar belt tightening. By pegging payroll growth at a more modest 1.5 percent per year, the county would have kept its payroll relatively flat in order to limit costs.

Annual payroll growth of 1.5 percent since 2001 would have yielded total savings of more than $2.7 billion. Those savings would have been over $320 million alone in 2016.

At a time when the county is facing yet another budget crisis, all solutions – including a freeze or reduction in payrolls – should be on the table.

Costly consequences in retirement

Preckwinkle’s payroll growth translates to higher costs in both the short-term and the long-term. As salaries grow faster than those of residents, employees have secured higher pensions as well. More than 2,200 Cook County workers receive salaries over $100,000 thanks to these generous increases. And for career county workers, that means pensions worth millions of dollars over the course of their retirements.

Taxpayers are left on the hook for these benefits.

Instead of piling on residents who already face some of the highest property and sales taxes in the nation, Cook County board members should find real solutions to the county’s fiscal crisis.

One such solution is sitting right under their noses – 401(k)-style retirement plans for new county workers. A standalone 401(k)-style retirement plan for state university workers has been operating successfully in Illinois for nearly two decades, with more than 20,000 members.

Until Preckwinkle gets serious about addressing payroll growth and introducing real pension reform, she should not be able to shirk responsibility for the county’s budget woes.