Coming up short: What if Illinois’ pension funds miss their investment targets?

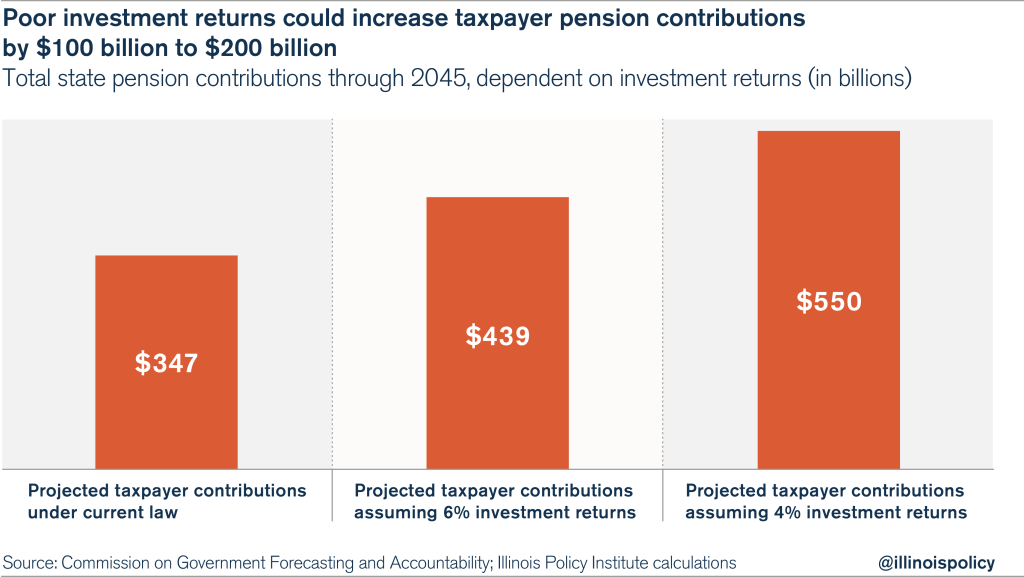

Without real reforms, low investment yearly returns of 4 to 6 percent over the next 28 years could cost Illinois taxpayers anywhere from $100 billion to $200 billion above what they’re already expected to pay in contributions.

Illinois has less than 50 cents of every dollar it needs to pay for teacher pensions.

Dick Ingram, the executive director of the Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, said as much in a statement reported by Reuters on Oct. 30. But that’s not all. TRS officials recently announced the pension fund received a 4.6 percent return on its investments for fiscal year 2015. This is a serious concern, since TRS needs, on average, 7.5 percent yearly returns to be able to fund teacher pensions over the long term.

Achieving high investment returns is critical to TRS, which, according to Reuters, ended fiscal year 2014 with only 42 cents for every dollar it needs today to pay out future benefits. Missing its investment target also increased the fund’s shortfall to $62.7 billion from $61.5 billion.

And since taxpayers are on the hook for bailing out Illinois’ government-worker pension funds when shortfalls occur, this latest underperformance raises an important question: What will happen to the pension funds, and taxpayers, if, in an era of expected low economic growth and low interest rates, subpar returns on investment become the new normal?

According to Illinois Policy Institute projections, without real reforms, low investment yearly returns of 4 to 6 percent over the next 28 years could cost Illinois taxpayers anywhere from $100 billion to $200 billion above what they’re already expected to pay in contributions.

The importance of investment returns

Investment returns are the primary sources of funding for pension systems, along with employee and employer contributions. When a pension fund doesn’t meet its assumed returns, it creates an overall shortfall in the fund. For government-worker pension systems, this means the cost to taxpayers grows because the state’s employer contributions must increase to make up for the shortfall.

One year of low returns does not necessarily mean a problem for TRS – in fact, it is to be expected when investing in the market. The average investment return over a long period of time is what really matters for the health of a pension fund.

In Illinois, the state’s five government-worker pension funds (for teachers, state workers, university employees, judges and lawmakers) assume a yearly investment return rate of 7 to 7.5 percent over the long term, depending on the system. TRS itself has achieved an average investment return of 9.1 percent over 30 years. But what if Illinois’ government-worker pension funds can no longer achieve those assumed rates due to changed market conditions?

Federal Reserve interest rates are near zero, and the economy may only grow at a rate of 2 percent a year, some analysts predict. Some economists and retirement watchdogs have warned that a future of slow growth means that many pension plans should temper their expectations and lower their assumed rates of return.

Illinois’ government-worker pension funds are no exception. Whatever their previous record for achieving their assumed rates of return, the weakness of the economy means these funds are at greater risk of missing their 7 to 7.5 percent investment targets in the future.

If that happens, taxpayers will be expected to pour billions of extra dollars into Illinois’ government-worker pension funds to make up for the lost investment income.

Projecting the cost of lower returns

To see how much the burden on taxpayers would increase, the Institute ran a projection of the state’s government-worker pension contributions that assumed:

- An average investment return of 4 to 6 percent annually from fiscal year 2017 to 2045

- State revenue growth at its 10-year historical average of 27 percent a year

- Current expected state government-worker pension contributions of $347 billion through 2045, as calculated based on the plans’ expected yearly 7 to 7.5 percent investment returns

According to Institute projections, returns of only 6 percent would result in almost $100 billion in additional costs to taxpayers over the next 28 years – up to $439 billion.

To put that in perspective, the five state government-worker pension funds project that taxpayers will need to contribute $350 billion over the next 28 years under their assumed investment return rate of 7.25 to 7.5 percent. Under 6 percent returns, that amount rises to $439 billion – a 26 percent increase.

And if the pension funds achieved a yearly return of only 4 percent over the next 28 years, Illinois taxpayers would owe $550 billion in contributions, an increase of over 58 percent.

What’s worse, the built-in repayment ramp for Illinois’ government-worker pensions will cause their overall cost to grow as a percentage of the state’s budget – even under the generous assumption that Illinois’ budget will grow 3.27 percent a year through 2045.

Under a 6 percent investment return scenario, Illinois’ government-worker pension contributions would rise from 20 percent of Illinois’ general fund in 2016 to 30 percent by 2045.

And under a 4 percent return scenario, Illinois’ government-worker pension contributions would grow to 50 percent of Illinois’ general fund by 2045.

Securing state worker retirements

With the economy growing slowly for the foreseeable future, there is an increased risk that lower returns, such as TRS’s recent 4.6 percent rate of return, may become the rule rather than the exception for government-worker pension funds in Illinois.

Such a scenario bodes ill for everyone, including the state, Illinois taxpayers and especially the government workers who depend on these pension systems for their retirements.

The best way for Illinois to decrease the risk of that outcome is for the state to enact real reforms that can reduce the cost of government-worker pensions for taxpayers.

Given the Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling on Senate Bill 1 in May, structural reforms to government-worker pension plans may need to wait until Illinois’ Constitution can be amended to allow them – or until the state’s government-worker unions agree to pension changes at the bargaining table. That, however, doesn’t mean nothing can be done to fix Illinois’ broken government-worker pension system.

There are still several reforms Illinois can undertake to lessen the cost of government-worker pensions and get itself on the right financial track.

Here is a list of what Illinois lawmakers can do immediately to address the state’s growing pension shortfall:

The General Assembly’s pension plan is the most bankrupt of the five state-run pensions – it only has 16 cents for every dollar it should have today to meet its future obligations. With no unions to oppose reforms, Illinois politicians should lead by example and transition their own pensions into self-managed plans such as 401(k)s.

2. Offer 401(k)s for new workers

The Supreme Court’s ruling on SB1 doesn’t affect retirement plans for new government workers. Illinois lawmakers should follow the lead of states across the country – from Michigan to Oklahoma to Alaska – and adopt self-managed plans for all new state and municipal workers.

3. Offer optional 401(k)s to current employees

Government workers shouldn’t be trapped in insolvent, politician-run retirement plans of which they have no ownership. It’s only fair for workers to have the option to control their own retirement plans.

4. Require all teachers to make contributions toward their own pensions

In Illinois, most public-school teachers don’t pay the required 9.4 percent employee contributions toward their own pensions. Instead, school districts pay, as a benefit, some or all of the teachers’ required payments. Eliminating teacher pension “pickups” could save Illinois school districts about $430 million annually.

5. Put pension costs where they belong

Currently, local school districts can get away with end-of-career salary spikes and other “sweeteners” that inflate future pensions because the actual pension costs of their employees are borne by the state – not the school districts. The annual cost of teacher pension benefits – nearly $1 billion – should be shifted away from the state to local school districts, where it belongs.

6. Limit the growth of pensionable salaries

Government-worker pension benefits are growing at a pace that far exceeds the growth of taxpayers to fund them. With no way to reform current workers’ pension benefits, the only way to control costs is to limit salary growth and other items that drive up pensionable salaries.

Bankruptcy should be the option of last resort, but it can help struggling municipalities restructure their debt, renegotiate contracts and reform pensions.