Chicago’s plan to pay off COVID-19 debt with federal aid hits a snag

Chicago had planned to use half of its federal relief funds to pay down pandemic debts, but new federal guidance may prevent that. Regardless, without pension reform the city will continue drowning in debt.

Chicago will get nearly $1.9 billion for COVID-19 relief from the American Rescue Plan Act, but the U.S. Treasury Department’s May 10 guidance upends the city’s plan to use half to pay down debt.

The state had similar plans for its $8.1 billion.

However, top Illinois Democrats are pushing U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to allow the state to use the new funds to pay back money Illinois borrowed during the pandemic from the Federal Reserve – the only state to do so. They argue the borrowing was a direct result of the pandemic and they should be allowed to repay it with coronavirus relief aid.

Chicago leaders also intend to seek further guidance on the rules. They, too, may argue the debts the city intends to repay resulted from the pandemic.

As Chicago now decides how to spend its share of the funds, Mayor Lori Lightfoot cautioned aldermen not to get too excited about fulfilling their wish lists. Lightfoot said the money comes with restrictions, such as a prohibition against funding pensions, and is “not a slush fund that [the city] can use” as aldermen please.

Lightfoot had hoped to use about half of the money, some $965 million, to pay off “scoop-and-toss” borrowing used to shore up a pandemic-induced budget shortfall. Those plans are now on hold thanks to the new rules.

The city has a history of scoop-and-toss borrowing in which new debt is used to pay off old debt. Both Lightfoot and Chief Financial Officer Jennie Huang Bennett have said the priority for the money must be to pay down debts for the long-term health of the city.

Lightfoot’s administration is right that paying down short-term debt is the most fiscally responsible use of the funds. Left unaddressed, the cost of servicing that debt would add to future fiscal pressures and threaten the city’s ability to provide services – exactly what the state and local fiscal recovery funds are intended to prevent.

Some aldermen are unconvinced of the urgency of shoring up Chicago’s shaky finances with the federal funds. They have called for a universal basic income program that would aid 5,000 of the city’s most needy residents with $500 a month.

When asked whether she supports creating a universal basic income program in Chicago, Lightfoot said, “I favor jobs. In the long-term, building a strong, robust and inclusive economy that deals people in from across the city is the best way that we can cure some of the economic woes that folks are facing.”

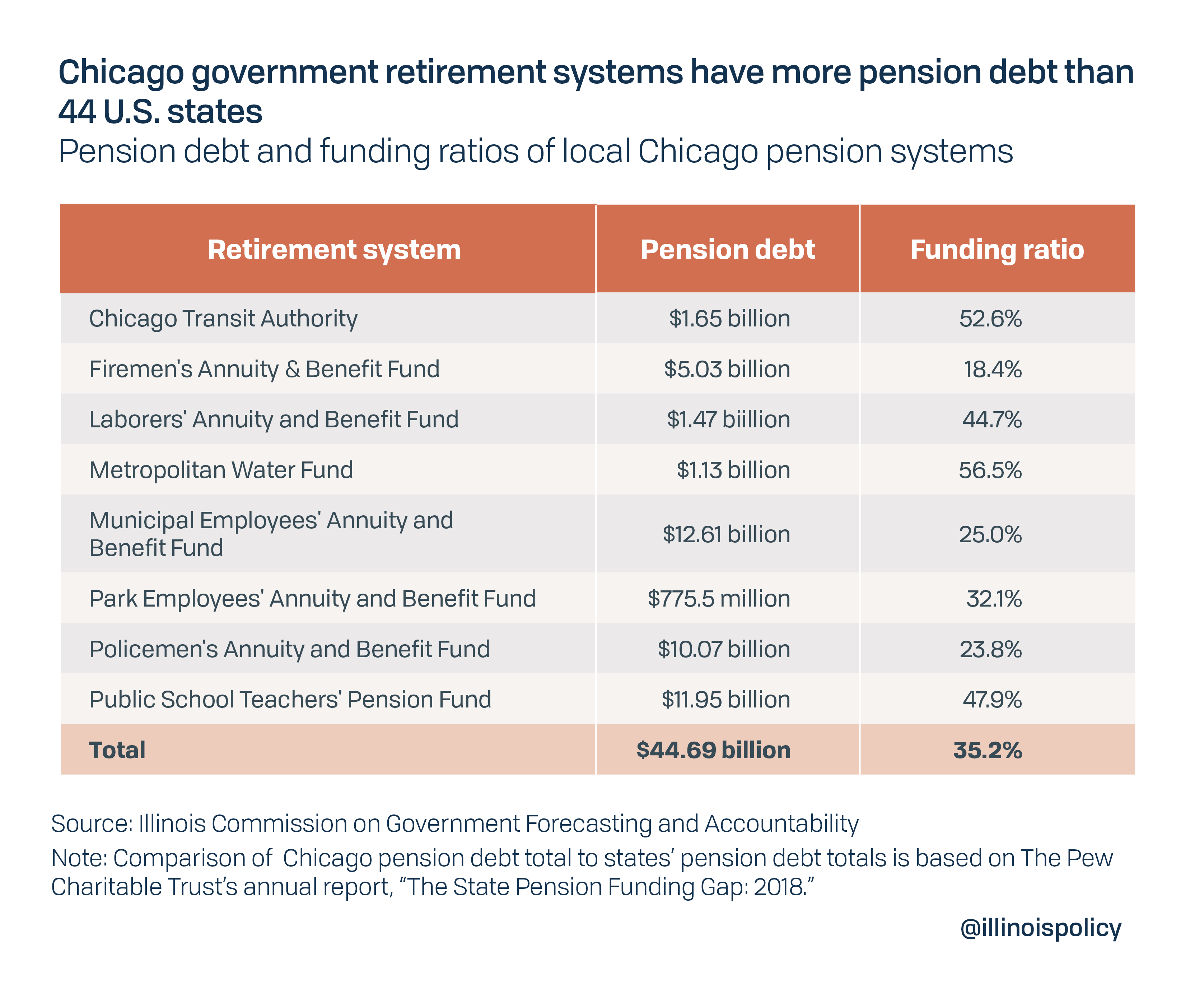

Economic growth will be difficult to achieve without addressing Chicago’s poor financial condition, which is driven by enormous pension debt and has led to increasing taxes, fines and fees. Chicago’s eight retirement systems have accumulated nearly $45 billion in debt – that’s more pension debt than 44 states.

Financial watchdog Truth in Accounting also recently ranked Chicago one of the worst sinkhole cities for its massive debts and troubled budgets. Each Chicago taxpayer would need to send $41,100 to the city just to pay off debt, amounting to the second-highest taxpayer burden in the nation. That doesn’t include the $52,000 each Illinoisan owed for state debt in 2020. In 2019, Chicago had just $10.05 billion available to pay $46.47 billion in unfunded pension and retiree health care benefits, bond debts and other liabilities.

It is important to remember the American Rescue Plan funding is a one-time cash infusion and not a long-term solution to the city’s financial problems. There are four authorized uses for the funds:

- Responding to public health needs and economic costs associated with the pandemic.

- Providing premium pay – which cannot exceed $13 per hour or $25,000 per worker – to essential employees.

- Replacing any lost revenues because of the pandemic.

- Investing in water, sewer and broadband infrastructure improvements.

The Act allows for significant flexibility in what the funding can be spent on within those four general categories. That flexibility can be a good thing for cities with strong fiscal foundations that can afford to add new programs or services to their budgets. For cash-strapped cities such as Chicago, the flexible funding will encourage city leaders to commit to costly new projects they will have to repay long after this federal funding is spent.

To achieve long-term fiscal health, Chicago must address out-of-control pension spending and begin to reverse its course toward insolvency. A one-time federal bailout will do nothing to solve those longstanding financial problems, but those problems will be worse if the federal funds are used for costly new social programs or even infrastructure improvements that will require new spending to maintain and upgrade long after this federal funding is spent.

Chicago’s chronically poor fiscal health has forced it to consider spending much of the aid on paying down debts.

Without structural pension reforms, Chicagoans will continue to be hit with tax increases and fines once the federal funds have all been spent.