Chicago’s 2020 budget proposal was never truly balanced

Faced with the impossible task of balancing Chicago’s budget without pension reform, Mayor Lori Lightfoot is forced to partially rely on phantom cuts and revenues.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot inherited a $838 million budget deficit for fiscal year 2020 the day she was sworn into office, an unwelcome surprise to say the least. Former Mayor Rahm Emanuel had claimed the deficit would be just $252 million but subsequent analysis by Lightfoot’s administration proved this number was far too low. More than a third of the increased deficit came from higher required contributions to the city’s pension funds.

Ultimately, it is impossible for Lightfoot or any other person to close Chicago’s long-term structural budget deficit without constitutional pension reform to slow the growth in future benefit increases. Emanuel had endorsed a constitutional amendment to allow structural pension reform but waited until he was on his way out the door. As a result, his endorsement carried much less weight with state lawmakers who need to approve the reforms.

So far, Lightfoot has sent mixed messages on pension reform and stopped short of endorsing an amendment. While the mayor has made public statements recognizing the need for structural pension reform – including criticizing 3% compounded post-retirement annual raises as “unsustainable” – these statements have always been walked back by the mayor’s communications staff.

Instead, Lightfoot was forced to be creative and cobble together a budget that relies on various targeted tax increases and some modest spending cuts. While the Mayor deserves credit for her ideas to make Chicago government more efficient, the proposed 2020 budget plan is not truly balanced. Many of the savings and revenue enhancements suggested in the budget are unlikely to materialize.

Until and unless Lightfoot becomes an advocate for a constitutional amendment and true pension reform, city taxpayers will continue to see tax hikes year after year and the city will continue to spend more than it brings in, as it has since at least 2003.

Lightfoot’s plan

Lightfoot first announced the $838 million gap when she released her 2020 Budget Forecast in September. After adding $51.8 million in new spending, the mayor then identified $352.2 million in increased revenue and $537.6 million in savings and efficiencies to bring the budget into balance.

To close the largest budget deficit in Chicago history, Lightfoot’s original budget plan proposed the following:

- $200 million in savings by refinancing existing debt to achieve lower interest rates. The mayor’s budget proposes frontloading all of these savings to the first year, rather than taking them over the course of the bonds’ lifetime, making this a one-time action that cannot be counted on in future years.

- $163 million by asking for higher reimbursement rates for emergency services, including $30 million from increased ambulance fees that require federal approval the city has yet to obtain.

- $148.7 million in savings by implementing zero-based budgeting for the first time, a budgetary practice through which every line item of spending is assumed to start at $0 and has to be justified anew each year.

- $141 million in lower costs from unspecified “improved fiscal management.”

- $50 million from a tax hike on the sale of real estate. The higher taxes would hit home sales above $1 million while home sales below $500,000 would see a decrease. Real estate transfers in the middle of that range would see no change.

- $47 million in new revenue by increasing taxes on ride sharing services, such as Uber and Lyft, for rides into or out of the downtown area. The mayor has also indicated this policy change is intended to reduce congestion and encourage the use of public transit.

- $31.4 million by declaring a surplus of funds in tax increment financing districts, a special form of economic development that captures property tax growth and diverts it to spending designed to grow the economy. If the city does not have enough projects on which to spend all its available TIF funds, the mayor can bring the money into the operating budget to be used for other purposes.

- $19.7 million in cuts related to leaving vacancies unfilled, reducing the number of city employees.

The remainder of the gap is supposed to be closed through a variety of smaller measures, including, new revenue from the sale of recreational cannabis, increased taxes on restaurants and merging some city departments.

Of the $51.8 million in discretionary spending increases, $10 million is for affordable housing and fighting homelessness, which had been a campaign priority for Lightfoot.

Unfortunately, several of the proposed revenue sources and savings measures are either dependent on uncertain approval from other governments or are unlikely to materialize. As a result, the 2020 Chicago budget proposal is not truly balanced.

Of the $352.2 million of new revenue in the original budget, $213 million – or over 60% – comes from sources that are not within the city’s immediate control. The $163 million from higher emergency service reimbursement rates has not been approved by the federal government. Similarly, the Illinois General Assembly did not grant Lightfoot’s request to increase the real estate transfer tax during its fall session. Lawmakers now couldn’t act on it until they return to session in late January, which is after the Chicago City Council must vote on the 2020 budget.

Hiking real estate transfer taxes would have been bad for Chicago’s already struggling housing market. As a result, the city would not likely see as much new revenue as officially projected. Real estate transfer taxes are also a volatile revenue source, making it unreliable during economic downturns. When the city increased the real estate transfer tax in 2008 to help the financially struggling Chicago Transit Authority, revenues came in far below projections.

The Chicago Tribune reports that to close the $50 million gap left by the failure of the transfer tax, Lightfoot proposed adding $15 million in additional savings from debt refinancing, $20 million more from a hiring slowdown that includes police and fire, and $15 million from various other sources including lower spending on health care and overtime for firefighters.

Because insufficient detail was given to explain the savings from zero-based budgeting and “improved fiscal management,” these figures may also prove overly optimistic.

A history of phony budgets with very real consequences

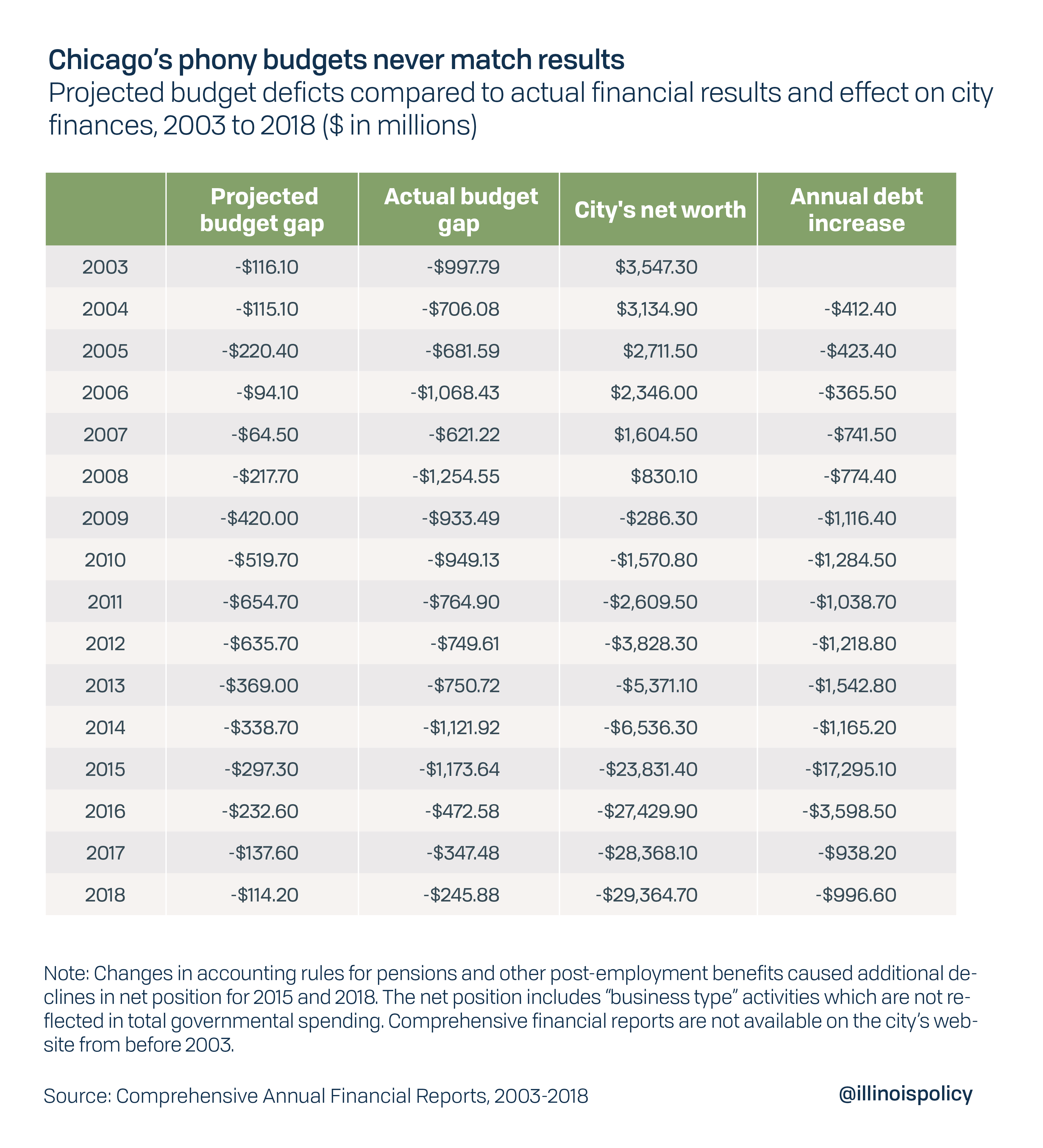

Since at least 2003, the city has annually spent more than the revenues it has received. That has contributed to a long decline in the city’s financial condition as reflected in its net position, which is similar to an individual’s net worth.

Discussion of Chicago’s budget gap typically focuses on the corporate fund used to pay basic day-to-day operating expenses, most of which is personnel costs. Other major expenditures, such as debt service or contributions to the city’s pension funds, are not included in the count and are funded through property taxes and other sources.

However, all of these funds are counted together as “total governmental funds” in the city’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports, or CAFRs. These reports give a much more accurate view of city finances than budget documents because they must rely on generally accepted accounting principles and are subject to independent audits. The city’s CAFRs show that its budget projections almost never match reality.

At the end of 2003, Chicago’s net position was a positive $3.5 billion, the amount by which its assets exceeded its liabilities. By 2018, after 16 years of spending more than it received and seeing pension liabilities continue to skyrocket, the city’s net position dropped by nearly $32 billion. As of the most recent audited financial report, the city’s total debt exceeded every asset it owns by more than $29 billion.

The budget gaps projected at the beginning of each year were off by billions of dollars in many years.

Excess spending was a chief cause, but it was not the only contributor to the growing net deficit. Changes in accounting rules for the calculation of pension obligations caused additional deterioration in the net position in 2015. Chicago had not previously included those obligations in its financial statements even though they were a significant obligation of the city. In 2018, other post-employment benefits, which mostly include health care costs for retirees, were added to the city’s balance sheet after another change in accounting rules.

This history of financial decline and inaccurate projections should make taxpayers wary of claims that the 2020 budget is balanced.

Long-term structural budget deficit remains

The Lightfoot administration has already projected budget gaps in excess of $1 billion in fiscal years 2021 and 2022. One-time steps taken to balance the 2020 budget won’t be available to help close those gaps. The $200 million in savings from bond refinancing cannot be done a second time, so that shortfall will have to be closed again next year through a different method. The TIF surplus declared for 2020 is unusually large and might also be unavailable in 2021, depending on how the mayor manages the TIF program.

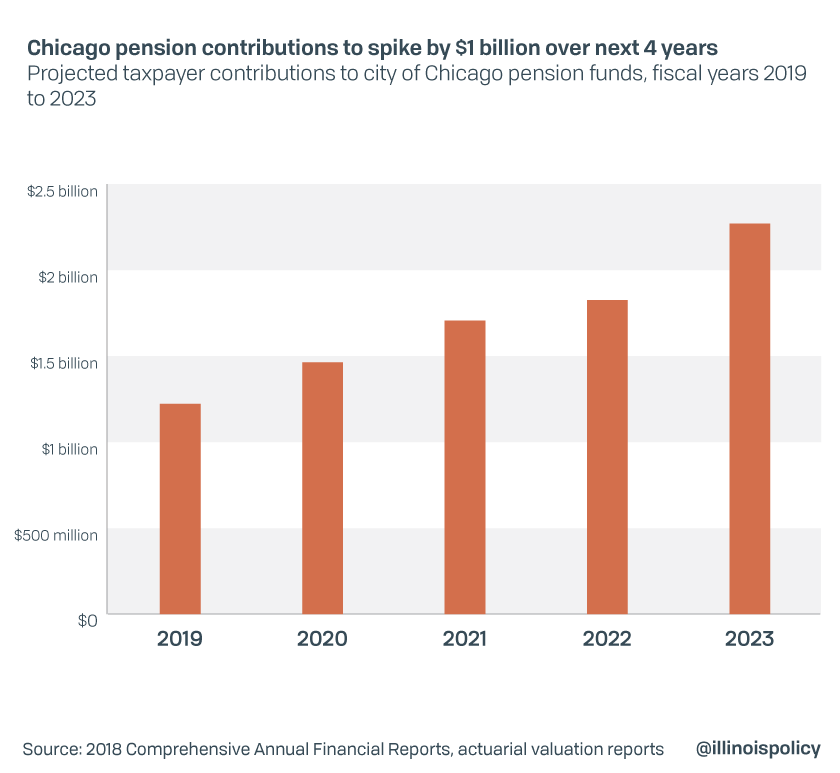

Despite any steps that the city might take, significant progress toward fiscal balance is impossible without pension reform. The city’s increasing required contributions to its four pension funds – for municipal employees, policemen, firefighters and laborers – will continue to strain Chicago’s budget.

The fiscal year 2020 pension payments are already $242 million more than they were in 2019. In 2021 it will grow by another $243 million. Pension costs will continue to spike in 2022 and 2023, by $118 million and $445 million, respectively. In other words, by the end of the mayor’s first term in 2023, pension contributions will be $1 billion more expensive than they were for 2019, the current budget year.

This growth in pension costs is unsustainable.

Pension contributions used to be made solely from property tax revenue, but $346 million will be required from the general fund in 2020, up from $101 million in 2018 and $136 million in 2019. Those dollars will be unavailable to pay for the city’s day-to-day operations.

Lightfoot is trying, but to succeed she must support pension reform

Lightfoot deserves credit for avoiding massive property tax increases.

Chicago taxpayers were recently subjected to $864 million in annual tax hikes during Emanuel’s administration. Included in that were $543 million in property tax hikes, $174.1 million in higher water and sewage taxes, and $147.1 million from an increase in the emergency 911 call fee. While these tax hikes were sold largely as a fix to the pension system, they have failed to solve the underlying problem of pension benefits that are more expensive than taxpayers can sustain.

Chicago’s high tax burden has contributed to four straight years of population loss for the city. Illinois already has one of the most punishing total tax burdens in the country, and this is the No. 1 reason residents cite for wanting to leave the state.

Overall, the 2020 Chicago property tax levy will increase by roughly $70 million compared to 2019. That’s equivalent to $47.89 in higher property taxes for the median homeowner for the Chicago budget alone. That’s on top of an at least $80 increase the typical homeowner may end up paying to finance the new Chicago Teacher’s Union contract.

But as reported by Greg Hinz in Crain’s Chicago Business, roughly $33 million of that increase was approved by the city council before Lightfoot took office. The only increase the mayor has proposed is $18.4 million to keep Chicago libraries open on Sunday. The remaining increase comes from new construction and natural property growth.

To put it in context of how it will impact families, Lightfoot is only responsible for $12.59 of the nearly $48 expected increase for the median homeowner. If she had elected to close the entire $838 million gap with property taxes, the median Chicago family could’ve seen a $573 increase in one year.

Lightfoot’s revised budget seems destined for approval despite the fact it is not truly balanced. That means city finances will continue to deteriorate and taxpayers will likely continue to be asked to pay more. Unless Lightfoot becomes an advocate for pension reform and helps convince the Illinois General Assembly to put a constitutional amendment on the ballot, she will be left with even fewer choices to muddle through the budget process than she had this year.

Without pension reform, massive property tax hikes are all but inevitable for Chicago residents.