Chicago Public Schools’ latest $500 million borrowing: More evidence it doesn’t deserve a bailout

Senate Bill 1 would force Illinois taxpayers to pick up the tab for CPS’ mismanagement of its finances.

CPS has refused to consider any structural or financial reforms after 20 years of district mismanagement, skipped pension payments, excessive borrowing, a collapsing credit rating and unaffordable teacher contracts.

The district’s financial woes are of its own making, yet state lawmakers are determined to bail out CPS with state taxpayer dollars.

That bailout is part of Illinois’ new education finance reform bill, Senate Bill 1. The bill forces the state to pay for CPS’ annual pension costs going forward while maintaining a special carveout for CPS that no other district receives. And it allows CPS to use its pension debt to appear poorer than it is when it applies for aid, granting the district even more state dollars.

On Aug. 1, Gov. Bruce Rauner issued an amendatory veto of SB 1 that stripped out the CPS bailout – among other changes – and sent the bill back to the General Assembly.

Rauner was right to strip the CPS bailout and other bad elements from SB 1. CPS does not deserve a bailout that will cost taxpayers across the state.

CPS’ history of poor management

The $500 million long-term bond offering Chicago Public Schools’ completed in July will saddle future taxpayers with $850 million in interest costs alone over the next 30 years, according to a report by the Chicago Tribune.

That bond deal is just the latest in a series of poor financial decisions and mismanagement that have led to a “junk” credit rating for CPS.

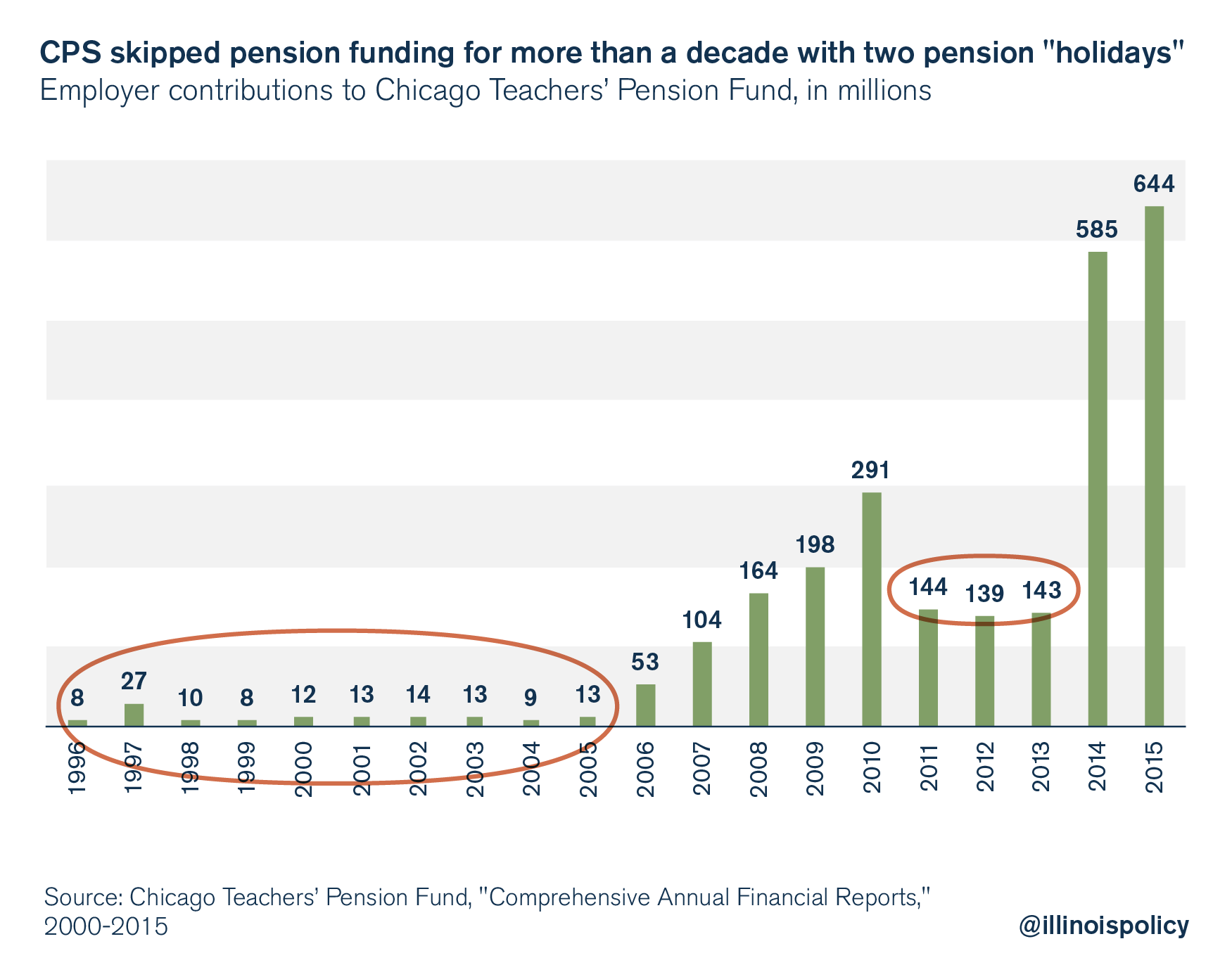

- CPS took “pension holidays” that created the teacher pension crisisAs part of a financial agreement in 1995, state lawmakers agreed to hand over control of the district and the teachers pension fund to then-Mayor Richard M. Daley.

Back then, the pension system was approaching 100 percent funded. Daley and CPS officials – with the consent of the Illinois General Assembly – enacted a 10-year pension holiday that diverted at least $1.5 billion from the pension system and toward school operations and teachers’ salaries.

CPS officials later received permission to enact another partial pension holiday from 2011 to 2013, diverting even more pension dollars to operations and salaries.

Today, the Chicago teachers pension fund is in serious crisis. It has half the money it needs on hand to pay out benefits.CPS is now forced to pour hundreds of millions of dollars into the pension fund each year to keep it from collapsing – money that could be going into the classroom to educate students.

- Rather than making pension payments, the district inflated salariesThe funds directed away from pensions during pension holidays went toward teacher compensation.

Overall, CPS payroll growth from 1998 to 2014 resulted in average covered payroll growing by 80 percent, almost twice the rate of inflation.

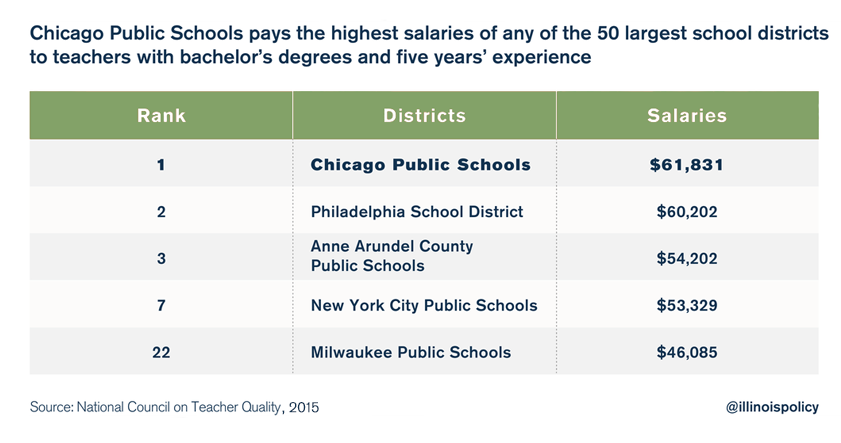

Today, Chicago teachers are the highest-paid in the nation among the country’s biggest school districts, according to an analysis by the National Council on Teacher Quality.

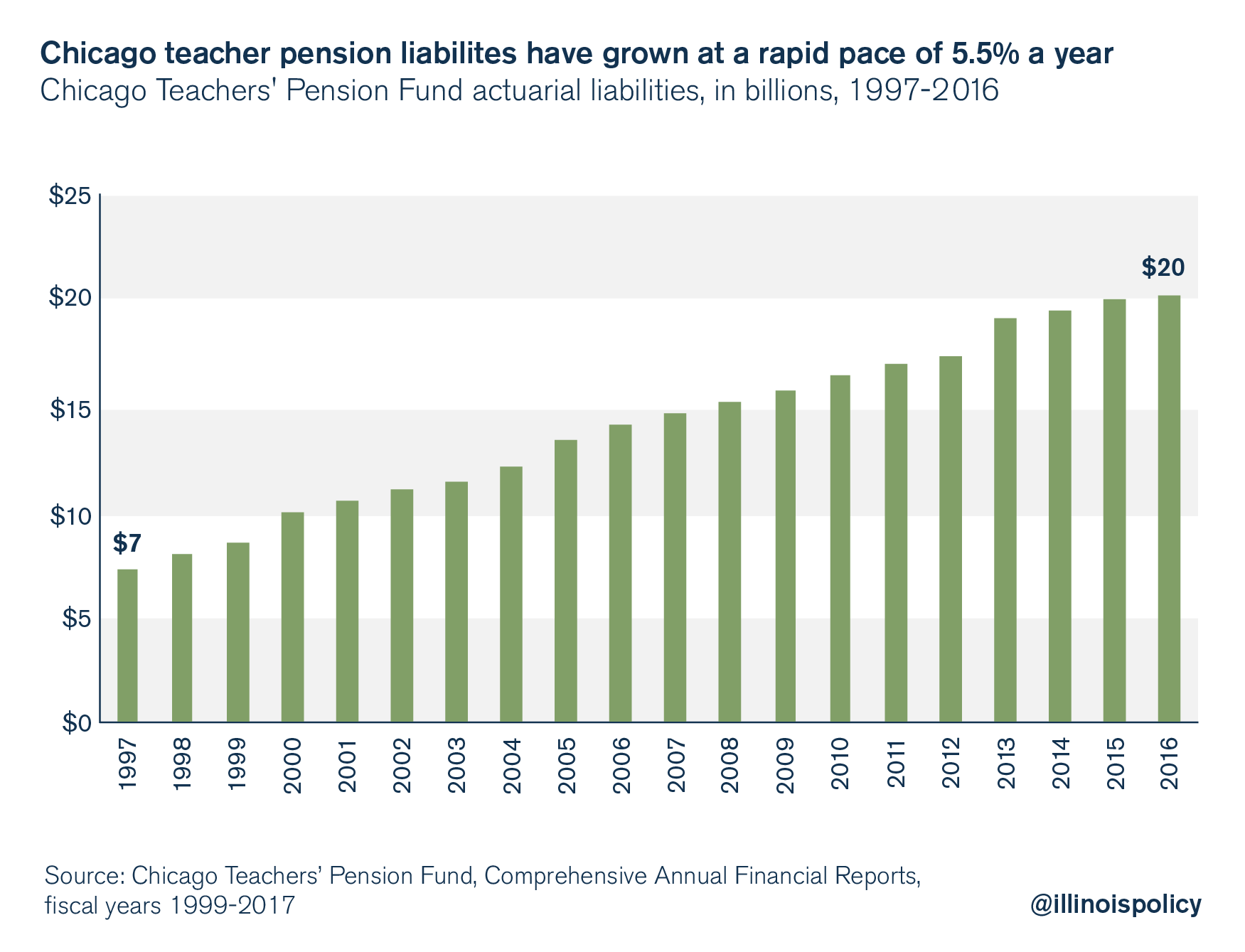

- Increasing salaries means increasing promised pension benefitsBecause pension benefits are calculated as a function of ending salary, the fact that CPS grew teacher salaries so rapidly meant that CPS’ accrued pension liabilities also grew quickly. For a system that is already virtually insolvent, these higher salaries only add to the district’s pension crisis.

Chicago teacher pension liabilities totaled $20 billion in 2016 – up from $7.2 billion in 1997. Accrued benefits for teachers grew at a rate of 5.5 percent annually, far faster than inflation, Chicago’s economy or household incomes.

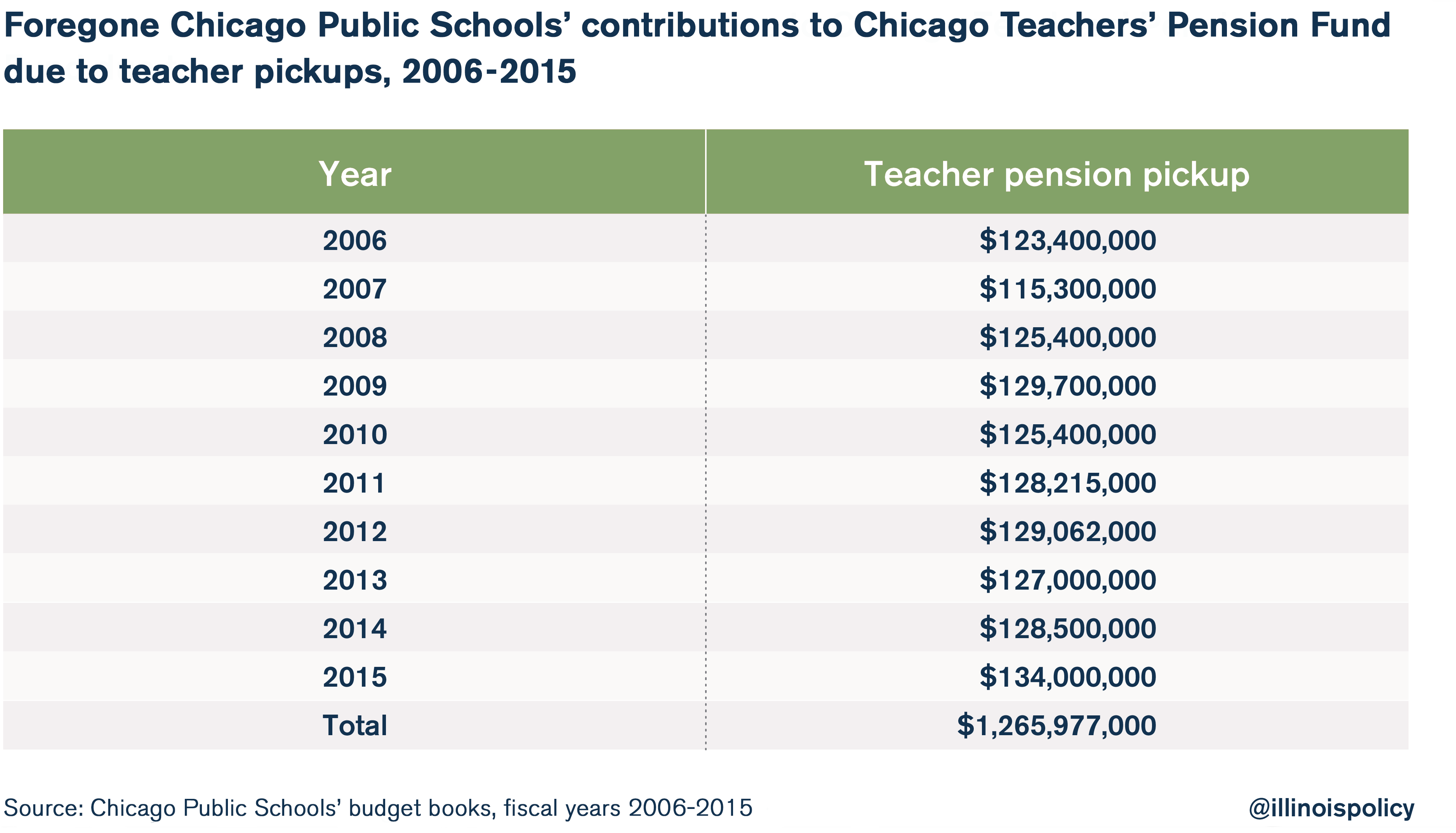

- The district has been paying teachers’ pension contributions for themAnother contributing factor to the crumbling of the CPS pension fund is teacher “pickups.”

Since 1981, CPS has been paying on behalf of teachers, or “picking up,” pension contributions worth 7 percent of teachers’ salary. (Chicago teachers are legally required to contribute 9 percent of their salary toward their pensions.) Between 2006 and 2015, the district spent over $1.2 billion covering the vast majority of teacher contributions to the pension fund.

Newly hired Chicago teachers are paying their employee contributions in accordance with the terms of the latest teachers contract. But a vast majority of teachers in CPS are still not contributing their full employee contribution.

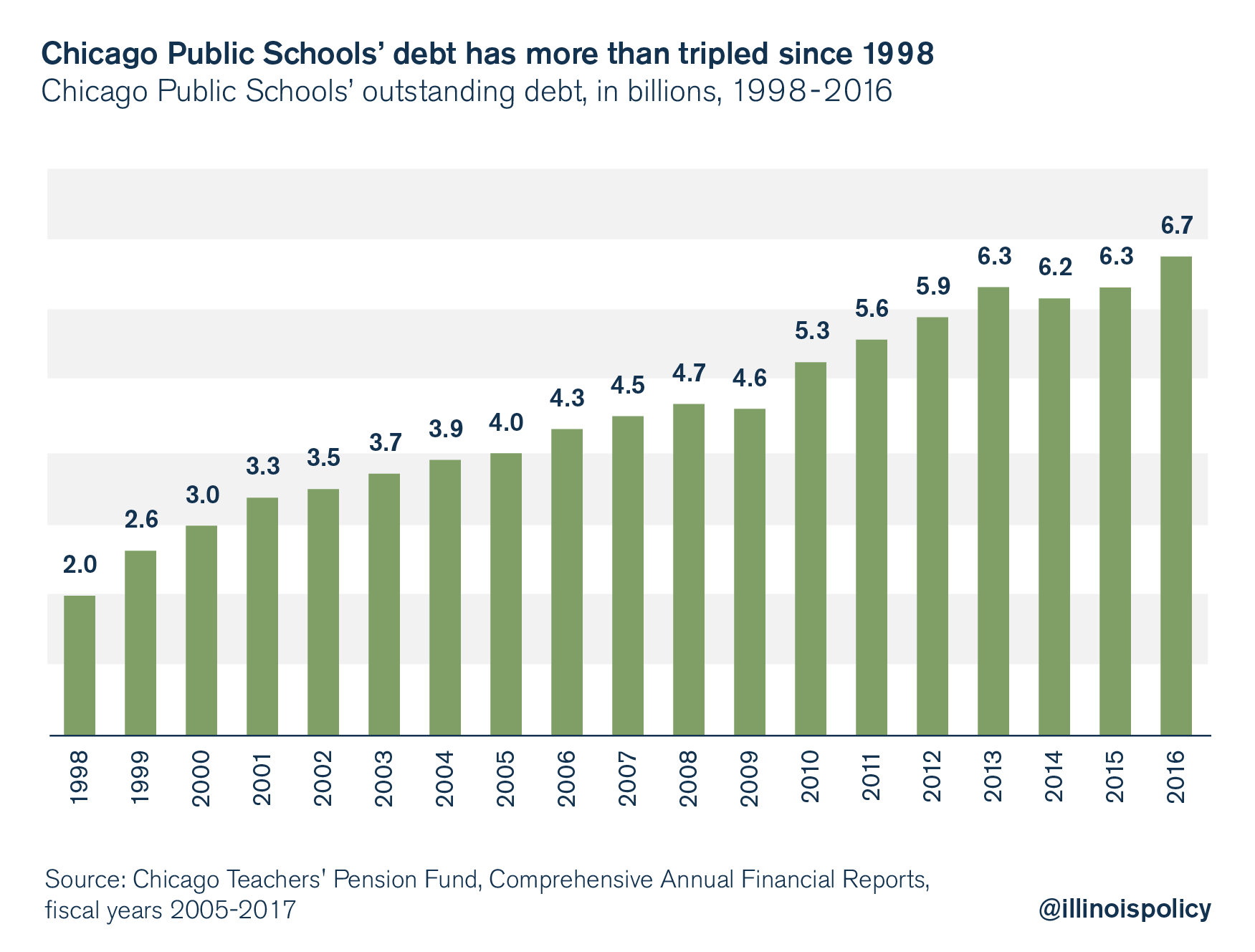

- CPS has been borrowing excessively for decadesIn addition to a history of poor financial decisions regarding the management of teacher pensions, salaries and benefits, CPS also has a history of borrowing beyond its means.

The district’s debt has been on the rise for decades, resulting in a current debt of over $6.7 billion – up from just $2 billion in 1998.

In June and July 2017, two separate debt issuances highlighted the poor borrowing decisions of CPS.

In June, the district borrowed $387 million to make its June pension payment – a payment it was still unable to make due to lack of funds. This bond issuance will cost taxpayers $70,000 a day in interest and cannot be paid off until at least Sept. 29 – resulting in accumulated interest of at least $7 million.

And in July, the district borrowed another $500 million. It is estimated that this loan will cost $850 million in interest alone over the next 30 years.

Real education reform

Lawmakers have a history of giving CPS what it wants. That comes at the expense of other districts across the state.

Instead of demanding a rewrite of the state’s education formula that includes a multibillion-dollar bailout, CPS needs to enact financial and management reforms it has avoided for decades.

The district should rein in spending, renegotiate contracts to provide affordable levels of employee compensation, and finally consolidate its schools and administrative bureaucracy to reduce operational costs.