Chicago area sees greatest population loss of any major U.S. city in 2015

Census data are sounding a warning signal that Chicago and Illinois policy leaders don’t necessarily want to hear.

The Chicago metro area is failing to attract and maintain population, according to data released March 24 by the U.S. Census Bureau. Compared to other major cities in the U.S., Chicago is the only city losing more people to other parts of the country than it gains from other parts of the world. Looking more locally to the Midwest, only Chicago and Cleveland shrank in population, with all other major cities in the Midwest growing in total population, even Detroit.

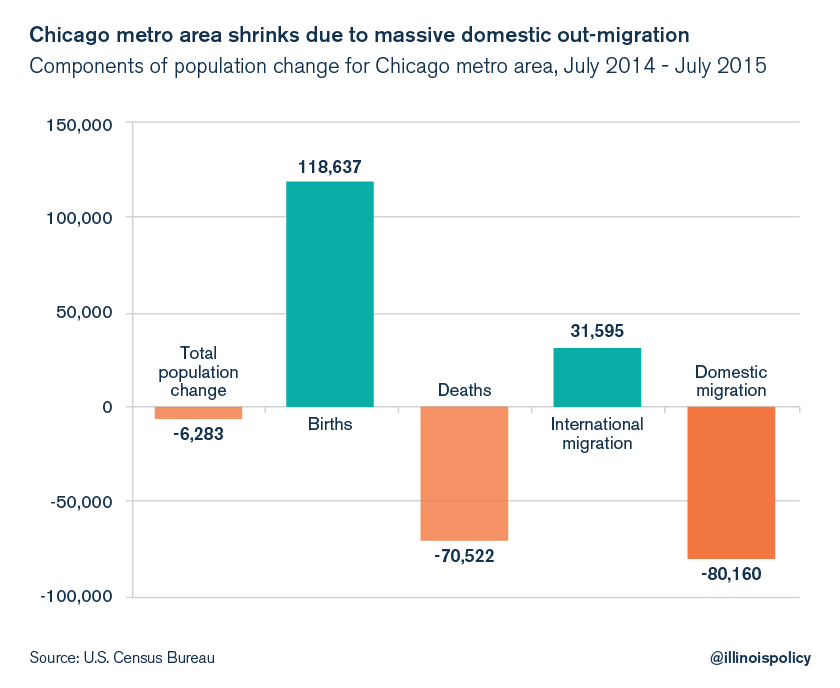

The Chicago metro area’s population shrank by 6,300 people between July 2014 and July 2015, according to census data. The shrinking population was driven by the area’s net loss of more than 80,000 people to other parts of the country. Even though the Chicago metro area gained people from births and international immigration, it lost more people due to deaths and domestic out-migration.

Chicago’s net loss of 80,000 people to other parts of the country ranks second-worst of all metro areas in the U.S., with the much larger New York City metro area losing 164,000 people to other parts of the country on net, and the Los Angeles metro area losing 71,000. However, both New York City and LA had international immigration gains that exactly offset their domestic migration losses. Chicago, on the other hand, gained only 31,600 people from international immigration while losing more than 80,000 people to domestic out-migration.

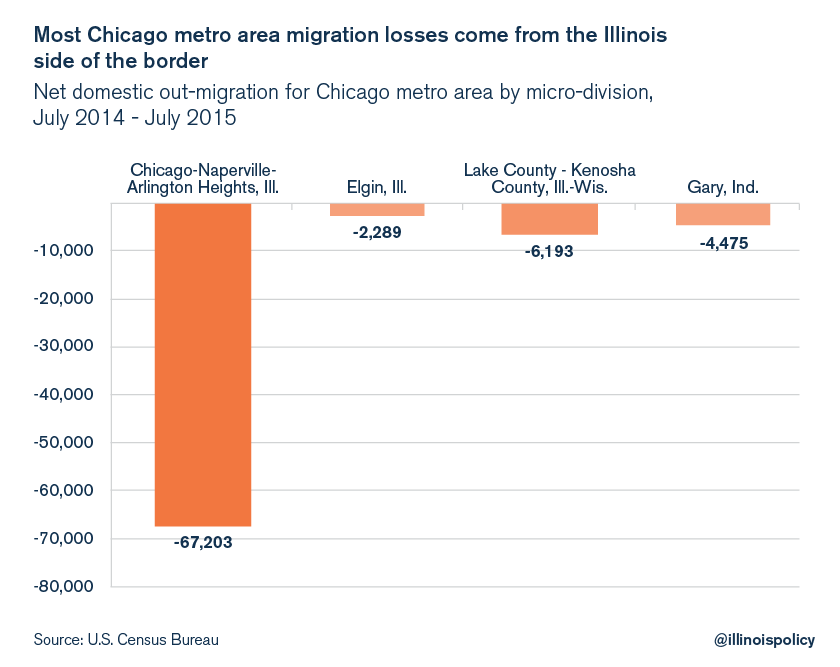

The domestic migration losses for the Chicago metro area mostly came from within Illinois’ borders. Of 80,000 people lost in net domestic migration, 67,000 were lost from the Chicago-Naperville-Arlington Heights, Ill., metro division; 2,300 from the Elgin, Ill., metro division; 6,200 from the Lake County-Kenosha County, Ill.-Wis., metro division; and 4,500 from the Gary, Ind., metro division. All of the Chicago and Elgin losses are from the Illinois side of the border, and presumably some of the migration losses from the Lake County-Kenosha County area come from the Illinois side of the border.

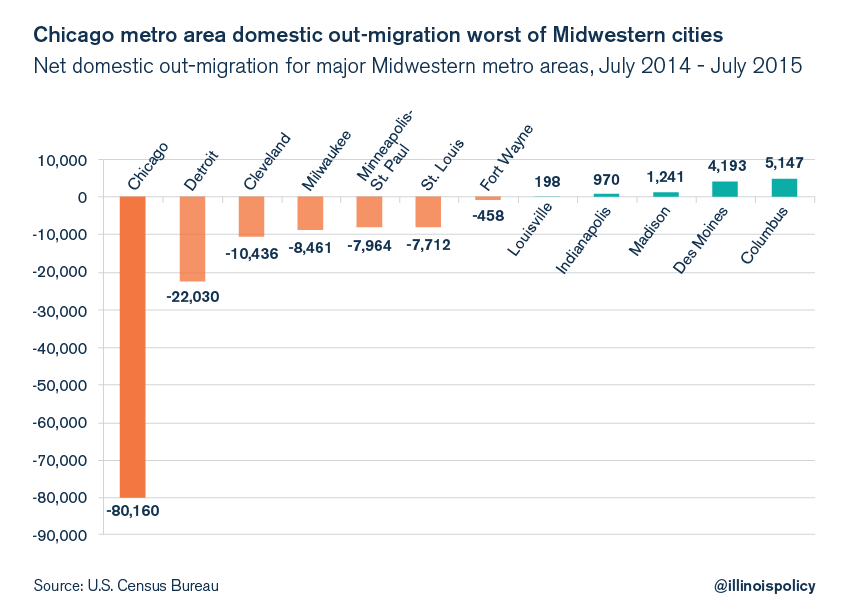

Looking at domestic migration gains and losses is one way to gauge the attractiveness and growth of cities compared with one another. And compared with other large cities in the Midwest, the Chicago metro area did not fare well. Of the 11 other large cities in the Midwest, six experienced net migration losses to the rest of the country and five experienced net migration gains from the rest of the country. After Chicago, the second-worst city for migration losses was Detroit, which lost 22,000 people to other parts of the country on net, while Cleveland lost more than 10,000. On the other side of the spectrum, Louisville, Indianapolis, Madison, Des Moines and Columbus experienced net migration gains from the rest of the U.S.

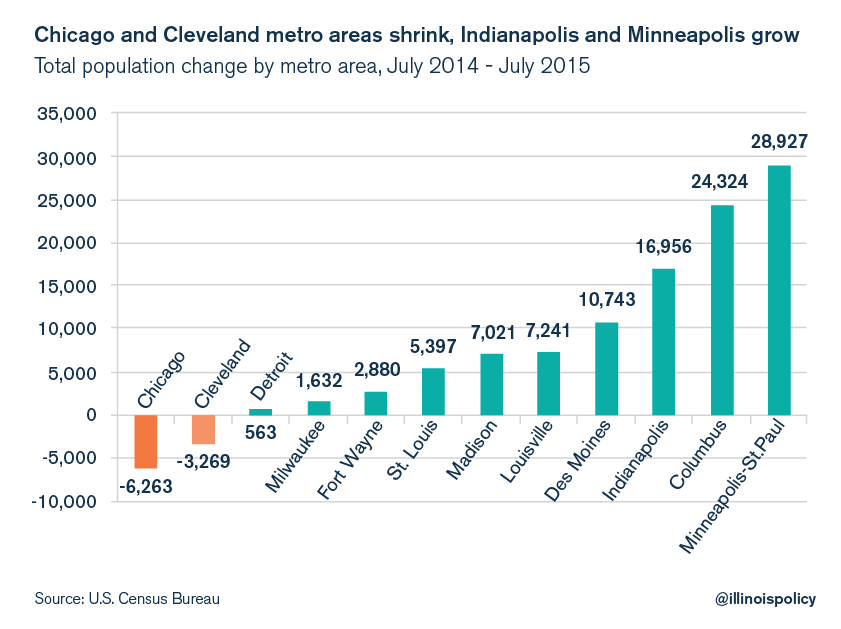

Domestic migration losses are one component of population change for these cities. Other components include international immigration gains, births and deaths. All told, only Chicago and Cleveland shrank in terms of total population, while all other large Midwestern cities grew, even Detroit. Some Midwestern cities are doing fairly well in growing their populations, including Des Moines, Indianapolis, Columbus and Minneapolis.

All of these data line up and sound a warning signal that Chicago and Illinois policy leaders don’t necessarily want to hear. When Detroit has population growth and Chicago’s population shrinks, that is a major red flag about Chicago’s future prospects. While the general trend is for Sun Belt cities to outgrow Rust Belt cities, the Chicago metro area is performing worst even among Rust Belt cities. Other Midwestern cities are doing quite well.

There are reasons to believe policy decisions made at the state and city level are going to make Chicago’s population problems worse. In 2015, Chicago dramatically raised property taxes while Cook County jacked up sales taxes, and those tax hikes both occurred after the period recorded in these census migration data.

With the finances of Chicago Public Schools on the brink, the city’s pension funds on a path towards insolvency and a massive minimum-wage hike pricing low-skill workers out of jobs, Chicago’s situation very well might get worse before it gets better.

Policy leaders should look at the results borne out in Chicago’s migration data, and consider that it doesn’t have to be this way. Chicago is not destined to suffer more than surrounding and peer cities, but the future will not turn brighter until policy decisions become more sensible. The migration results provide an opportunity to pause, reflect on the path Chicago has been on, and consider going another way.