Changes to federal SALT deduction expose Illinois’ high taxes

House Bill 4237 seeks to get around Congress’ limitation of a federal deduction that benefits high-tax states, but residents would be better served by efforts to directly reduce state and local taxes in Illinois.

With federal reforms casting Illinois’ high state and local taxes into relief, Springfield is in search of a workaround.

In December 2017, the U.S. Congress passed and President Donald Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, or TCJA, which lowered the corporate tax rate to 21 percent from 35 percent, cut personal income taxes by $2,059 for a family earning the median household income, and limited the state and local tax, or SALT, deduction, among other changes.

Since then, state lawmakers in Illinois and other high-tax states have been looking for a way to minimize the effect of the SALT deduction limitation.

Under the TCJA, taxpayers are only allowed to deduct $10,000 of their state and local taxes from their federal income tax liability. Proponents of this new limitation argue the SALT deduction acts as a subsidy for states with high taxes, such as Illinois.

On May 24, the Illinois Senate passed an amended House Bill 4237 by a 54-1 vote, with one senator voting “present,” in an attempt to circumnavigate the TCJA. The Illinois House passed a different version of this bill in April by a 93-15 margin. While the amended bill passed by the Senate was not voted on by the House before the regular legislative session ended in May, it appears the House has the votes needed to approve the Senate bill in the future.

The amended bill creates the Illinois Education Excellence Fund, which is described as a public charity, and also authorizes Illinois counties to establish charitable funds to which taxpayers can donate amounts that can be credited against their property tax bills. This is an attempt to circumvent limitations placed on the SALT deduction by the TCJA by allowing residents to pay their state income and local property taxes to special funds and claim a charitable deduction on their federal taxes.

However, based on public statements, the IRS might not accept these tax workarounds. In May, the IRS gave notice that it will propose new regulations to address these state-created mechanisms. The IRS emphasized that it will judge SALT workaround schemes based on their substance, not technical form, which means Illinois taxpayers could run afoul of federal tax law if they choose to pay into local government charitable funds or the Illinois Education Excellence Fund and claim their payments as charitable tax deductions on their federal tax forms. The Internal Revenue Code states that taxpayers are only eligible for a charitable deduction if the donation primarily serves a public purpose, and it’s possible the IRS will view the Senate’s amended bill as primarily serving a private interest of reducing an individual’s tax bill.

At least one lawmaker in Illinois has taken note of this fact. State Sen. Jim Oberweis, R-Sugar Grove, was the only member of the Senate to vote no on Illinois’ SALT deduction workaround. He said the IRS is not “going to allow states to pull a fast one like that, to find a tricky way around the deduction limits,” according to the Aurora Beacon-News. Taxpayers could lose under this bill since they – not lawmakers – would be subject to any penalties the IRS might impose.

Some lawmakers have argued this workaround is necessary to address the effects of the new federal law on Illinois residents’ tax burdens, and believe they should act to lower those tax bills by any means necessary.

But some of the lawmakers in support of the SALT workaround also voted to raise state income taxes in 2011 and 2017. Others voted in May for a resolution in favor of a progressive income tax in Illinois. Progressive tax plans are often sold as a tax on the rich, but the only plan proposed with specific rates would raise taxes on Illinoisans making as little as $17,300.

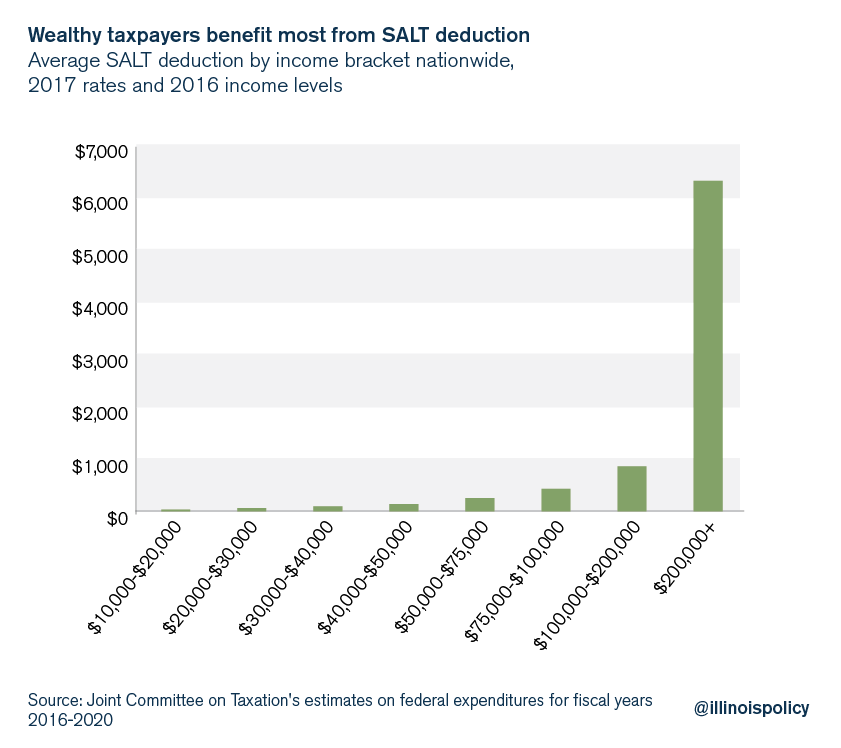

Interestingly, the uncapped SALT deduction primarily benefitted wealthier taxpayers, who are likelier than lower-income taxpayers to itemize their deductions rather than take the standard deduction. Before Congress limited the SALT deduction, 88 percent of the benefits of this provision flowed to taxpayers who make over $100,000 annually, according to the nonpartisan Tax Foundation.

Rather than focusing on a program that might not pass muster with the IRS, state and local lawmakers should address overspending and lower the resulting sky-high state and local taxes that make the SALT deduction limitation such an issue. This would not only help Illinois taxpayers, but would also make Illinois more competitive, and give residents and businesses more reason to stay and put down roots in the state.