Call waiting: Chicago Police Department refusing to release cellphone-tracking info

The Chicago Police Department is refusing to disclose information regarding its use of covert cellphone-tracking devices, which can intercept the personal information of innocent bystanders.

How has the Chicago Police Department been tracking cellphone activity? And what safeguards have been set up to prevent abuse? That’s what a lawsuit filed by privacy activists last year aims to figure out.

A report by the Chicago Sun-Times highlights a lawsuit challenging the Chicago Police Department’s refusal to release records regarding its use of covert cellphone-tracking devices, which can intercept the personal information of innocent bystanders. The city claims the devices are only used in investigating kidnappings, murders and other serious crimes.

But the secrecy with which the department administers the program has made these claims nearly impossible to verify.

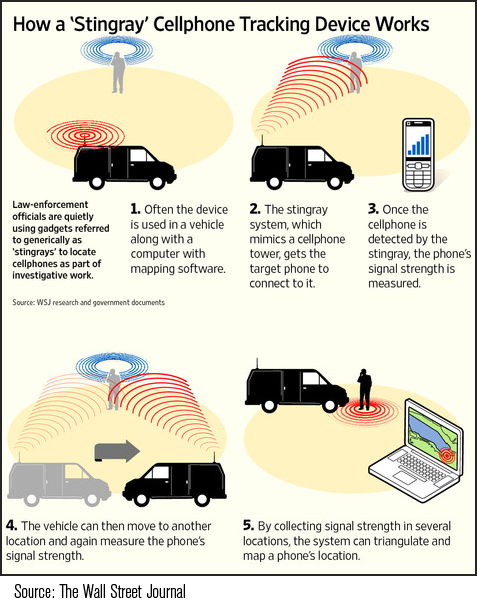

What taxpayers do know is that Chicago has spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on “StingRay” devices that track a user’s location by intercepting his or her cellphone signal.

Chicago Police Department officials have said federal law prohibits releasing information about how these devices are used. Chicago purchased the devices from the Harris Corporation, a company that sells similar products to local, state and federal law-enforcement agencies across the country. They’ve also signed a nondisclosure agreement with Harris, forbidding them from releasing information on how the devices work (see a sample agreement here). But like any public agency, the city has an obligation to comply with the state’s Freedom of Information Act.

One problem with the city’s cellphone tracking is that the devices intercept cell signals indiscriminately. Any nearby cellphone will automatically connect with the towers the city uses for tracking and give police officers the cell user’s personal metadata. This includes information such as one’s location, records of calls made and texts sent, and payment records. Metadata can reveal a lot about a person, even if it doesn’t include the content of messages and phone calls.

What happens to the personal information of anyone not specifically targeted for police surveillance? And even if one trusts police-department claims that officers only use these devices in the course of investigating serious crimes, who decides whether and when the police can use them? Does a warrant have to be issued first?

According to Matthew Topic, the attorney bringing the lawsuit against CPD, these are important questions that can’t be ignored.

“Theoretically, there could be legitimate uses for this equipment, but there are serious constitutional concerns if warrants aren’t being obtained and if the equipment also takes cellphone information from the hundreds or thousands of other people in the vicinity of purportedly legitimate targets,” he said.

It’s not enough to simply take the Chicago Police Department’s assurances at face value. Only greater transparency about how the department is using these trackers, accompanied by clear, strictly enforced rules, can prevent abuse.

Image credit: Johan Larsson