Blank check: Illinois lawmakers file progressive income tax amendment

An amendment to scrap Illinois’ constitutional flat tax protection is gaining sponsors in the Illinois Senate. Lawmakers have refused to discuss rates since those details killed the last progressive tax attempt.

Just weeks into the 101st Illinois General Assembly’s legislative session, lawmakers are adding their names to a resolution to eliminate the state constitution’s flat income tax protection.

But Illinoisans have no way of knowing just how much more they’ll end up paying under a progressive tax.

On Jan. 29, state Sen. Don Harmon, D-Oak Park, filed Senate Joint Resolution Constitutional Amendment 1, which would scrap the state’s constitutional flat tax protection and allow lawmakers to tax people differently based on income level. The amendment was not accompanied by a bill or statement proposing specific tax rates.

In other words, voters are being asked for a blank check that would give politicians the ability to charge different rates to different groups of people without any details on the tax rates.

Illinoisans should be wary: While proponents make many claims about the progressive tax, the reality is far different. Progressive tax schemes masquerade as a tax on the rich, but they are really a middle-class tax hike. They can cause long-term economic damage that hurts the very people progressive tax advocates say they want to help.

Here are six myths about the progressive income tax that Illinoisans deserve to know:

Myth No. 1: The rich don’t pay their fair share under a flat tax system.

Reality: Under a flat (i.e. proportional) tax system, the rich already pay most of the income taxes.

Proponents of a progressive income tax hike often mistakenly claim that wealthy income earners don’t pay their “fair share” under a flat tax system. Data from the Illinois Department of Revenue show the opposite.

Though progressive tax proponents often fail to define their terms, including who they believe is “rich” and what “fair” means, a reasonable definition of fairness is proportionality: the idea that people should pay about the same share of taxes as the share of the income they receive.

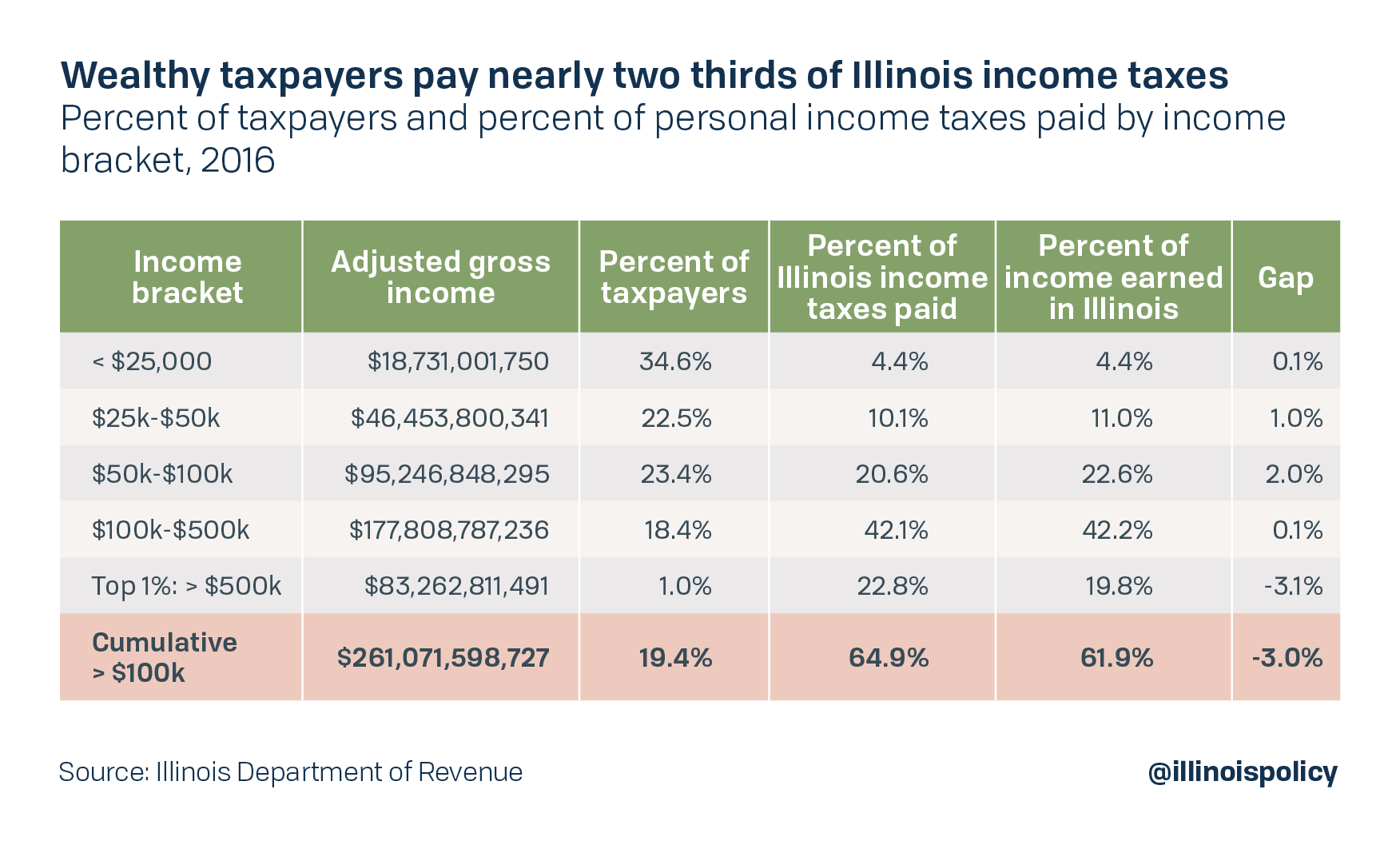

In 2016, the most recent year of data available, tax filers earning more than $100,000 per year made up 19.4 percent of taxpayers. This group earned 62 percent of the state’s income and paid roughly 65 percent of all personal income taxes, or nearly two thirds.

The top 1 percent of taxpayers, those making more than $500,000 per year, paid nearly 23 percent of all income taxes while earning about 20 percent of all income, a gap of 3 percent.

All other income groups earn a larger share of total income than their share of the total tax burden.

The simple reason for this phenomenon is the standard deduction in Illinois – which dropped from $2,225 to $2,000 in 2018 – exempts a larger percentage of a taxpayer’s income the less money they make. This exemption creates a slightly progressive tax system for the effective rate, or actual income taxes paid as a percentage of income earned, even with a flat nominal rate, which exists only on paper.

Myth #2: A progressive tax hike will lead to lower property taxes

Reality: A progressive tax hike will do nothing to lower property taxes

Some proponents of progressive taxes claim they can be used to reduce Illinois’ property taxes, which studies have ranked second highest in the nation. This claim is dubious for several reasons.

First, the chief causes of high property taxes in Illinois are the existence of too many layers of local government, which at nearly 7,000 gives Illinois by far the most in the nation. Too much government includes too many school districts, which take up about two-thirds of property taxes statewide. All that excess government consumes salaries, benefits and pension costs. It is a myth that Illinois property taxes are high because of insufficient state aid for local government resulting from Illinois’ flat tax.

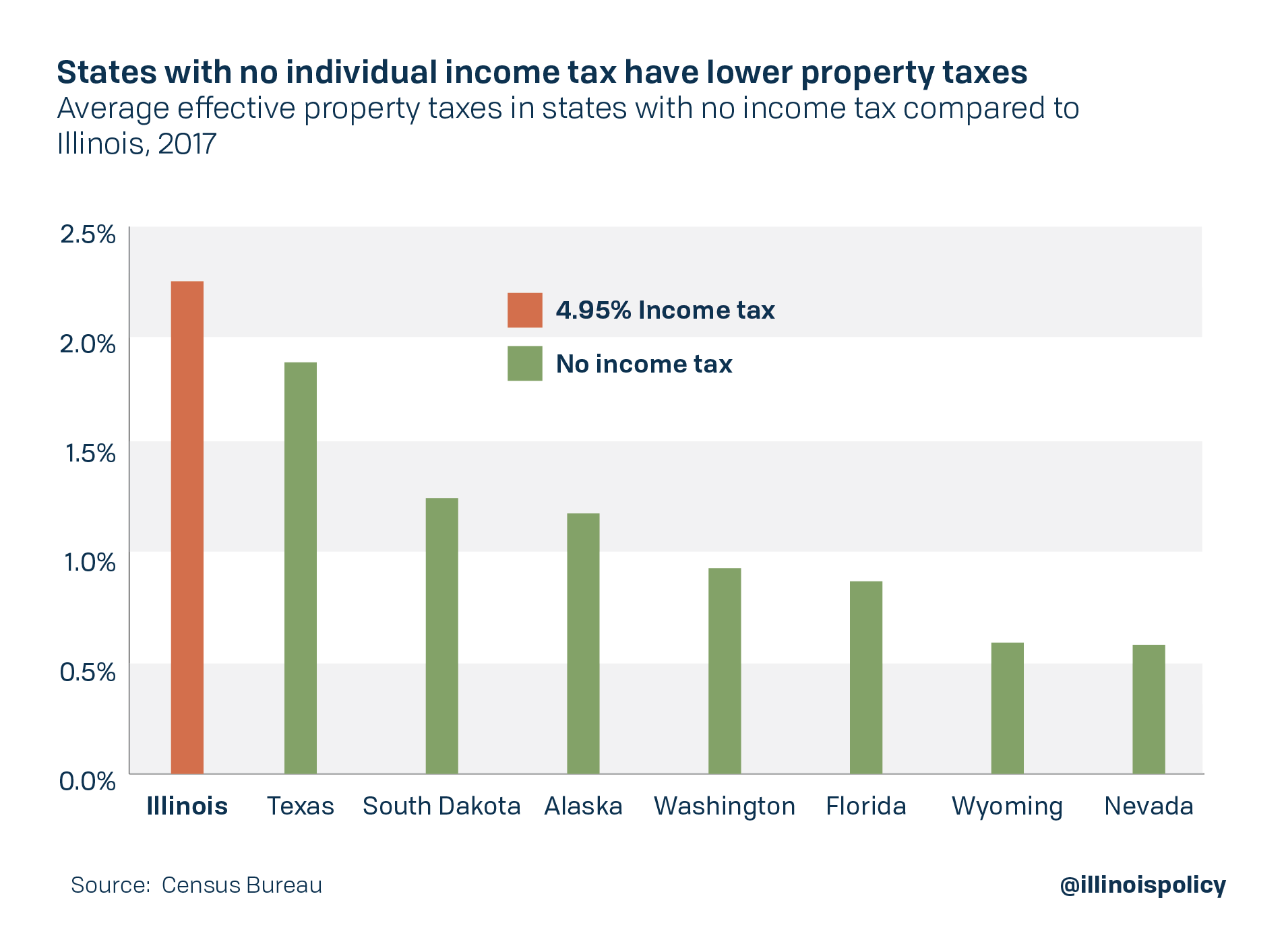

In fact, all seven states that have no income tax also have lower property taxes than Illinois, meaning they’re able to fund both state and local government services without high property taxes or a progressive income tax.

Second, none of the progressive tax proponents so far have include a mechanism that would guarantee property taxes are actually reduced. Without some mechanism limiting property taxes, such as a state-imposed freeze or cap, local governments can simply take additional revenue from the state while continuing to increase local taxes.

Bureaucratic agencies are “budget maximizers” that seek to grow their own size and revenue; public choice economists such as William Niskanen in the journal “The American Economic Review” have argued this since at least 1968.

This experience has been borne out in other states. Connecticut lawmakers also promised property tax relief when they switched from a flat tax to a progressive tax in the 1990s, but property taxes as a share of personal income have actually increased since the switch.

Myth #3: A progressive tax will allow Illinois to cut taxes for the middle class while providing more revenue to solve the state’s fiscal problems.

Reality: A progressive tax cannot fulfill all the promises attached to it – and often leads to higher taxes on the middle class.

Proponents of a progressive tax have claimed that it can close the state’s deficit, pay off its debt, fund billions of dollars of new spending and still provide a tax cut for the vast majority of Illinoisans. In reality, a progressive tax is not a silver bullet that can accomplish all of these goals simultaneously, or any of them in the long run.

This is especially true if a progressive tax applies only to the very wealthy.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker has previously said that a progressive tax hike should “raise taxes on people like Bruce Rauner and me.” Even setting aside levels of wealth such as Pritzker’s and Rauner’s, according to data from the Internal Revenue Service, just 0.3 percent of Illinois tax returns reported income of over $1 million in 2016. There simply aren’t enough rich people in the state to finance fixing the state’s financial problems, even assuming they remained in the state to pay the higher tax bill.

And New York show us they will not stay. New York’s governor and comptroller have both said the outmigration from the top 1 percent of income earners – who pay nearly half of all New York income taxes – is mainly to blame for a $2.3 billion budget hole.

Adjusted gross income, or AGI – the taxable base for the personal income tax – is essentially a rightward skewed bell curve. Although the wealthiest Illinoisans individually have a lot of money, their low number means that most of the potential tax revenue rests with the middle class and upper middle class. In fact, those making between $50,000 and $100,000 annually have over $95 billion – that’s $12 billion more in cumulative AGI than the top 1 percent of taxpayers, according to data from the Illinois Department of Revenue.

In looking at examples of detailed progressive tax plans in Illinois, this reality becomes even clearer. A progressive tax proposal from the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, or CTBA, would hike taxes on anyone earning more than $300,000 a year – about 2 percent of Illinois taxpayers according to CTBA’s calculations – but would have only raised $2 billion in additional revenues per year, according to a static estimate (assuming no negative economic effects of higher taxes).

The state’s annual deficit is projected to be $2.8 billion next year, and the bill backlog is projected to end the year at $7.8 billion. The CTBA plan wouldn’t come close to solving even a single year’s deficit or paying off the bill backlog.

Worse, the CTBA plan proposes negligible tax relief for the bottom 98 percent of taxpayers. The $300 cut the plan proposes for Illinoisans making less than $300,000 per year is less than the $732 income tax hike on the median income family in 2017, which also failed to solve the state’s problems.

And the last time an Illinois lawmaker proposed a specific rate schedule for a progressive tax, it would have increased taxes on anyone making more than $17,300 per year.

Myth #4: A progressive tax won’t harm the economy, or will actually help it

Reality: States with progressive taxes grow jobs, wages and GDP more slowly

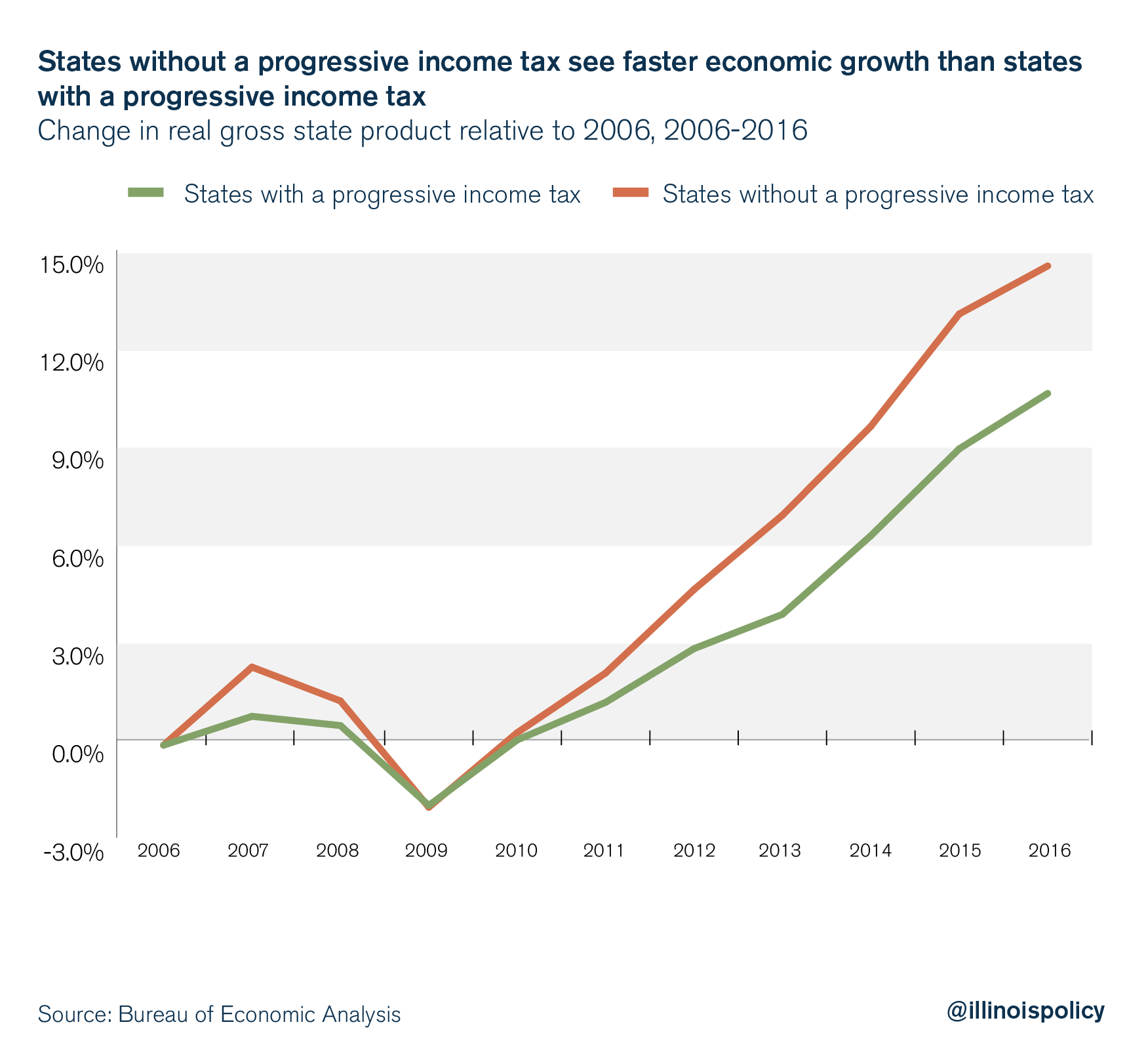

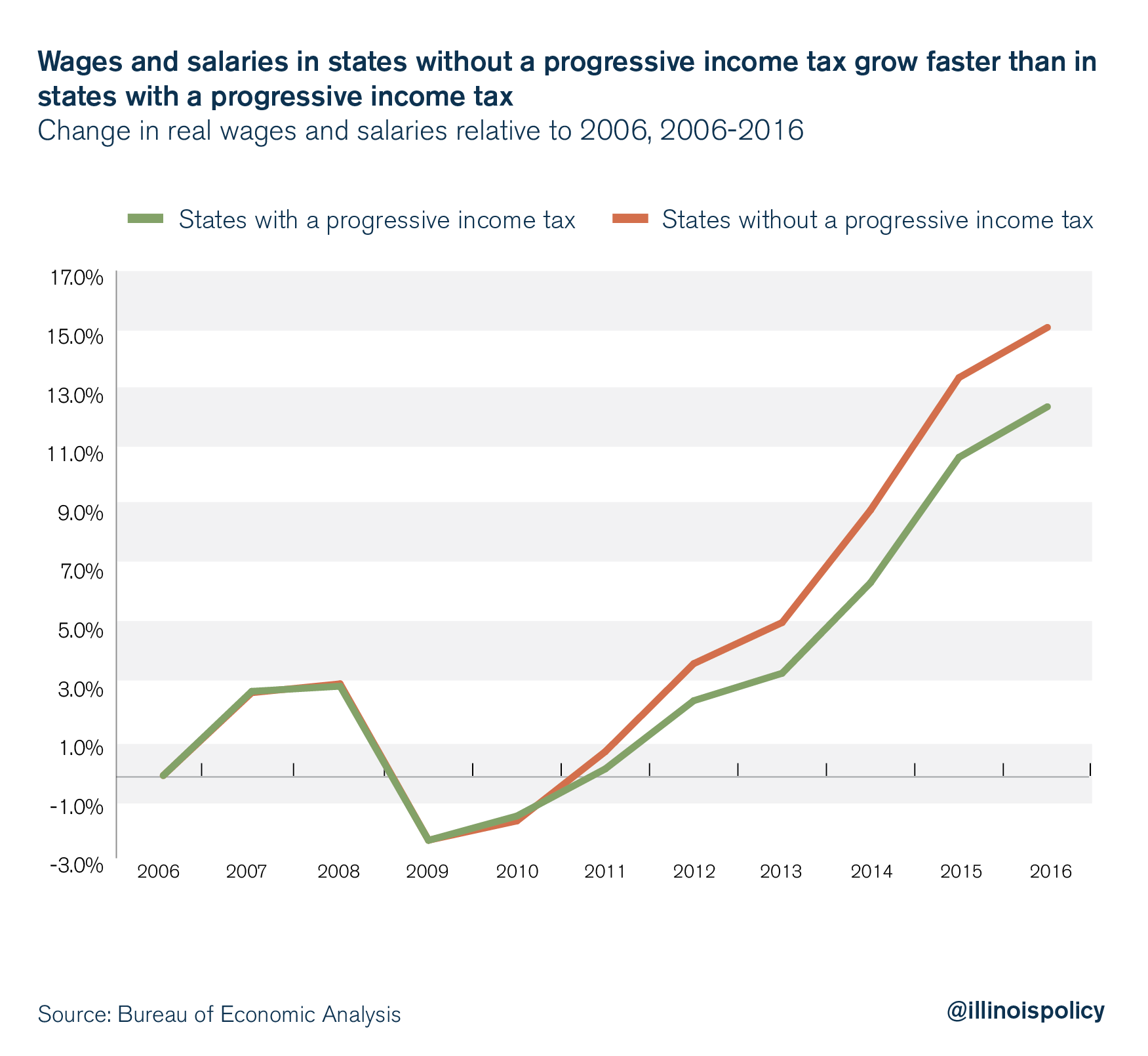

Examining the past decade of the most recently available macroeconomic data reveals overall economic activity – measured as real gross state product, or GSP – has grown faster in states without a progressive income tax than in states with a progressive income tax. Since 2006, states without a progressive income tax have seen GSP grow by 14.7 percent, while states with a progressive income tax have seen 10.8 percent GSP growth.

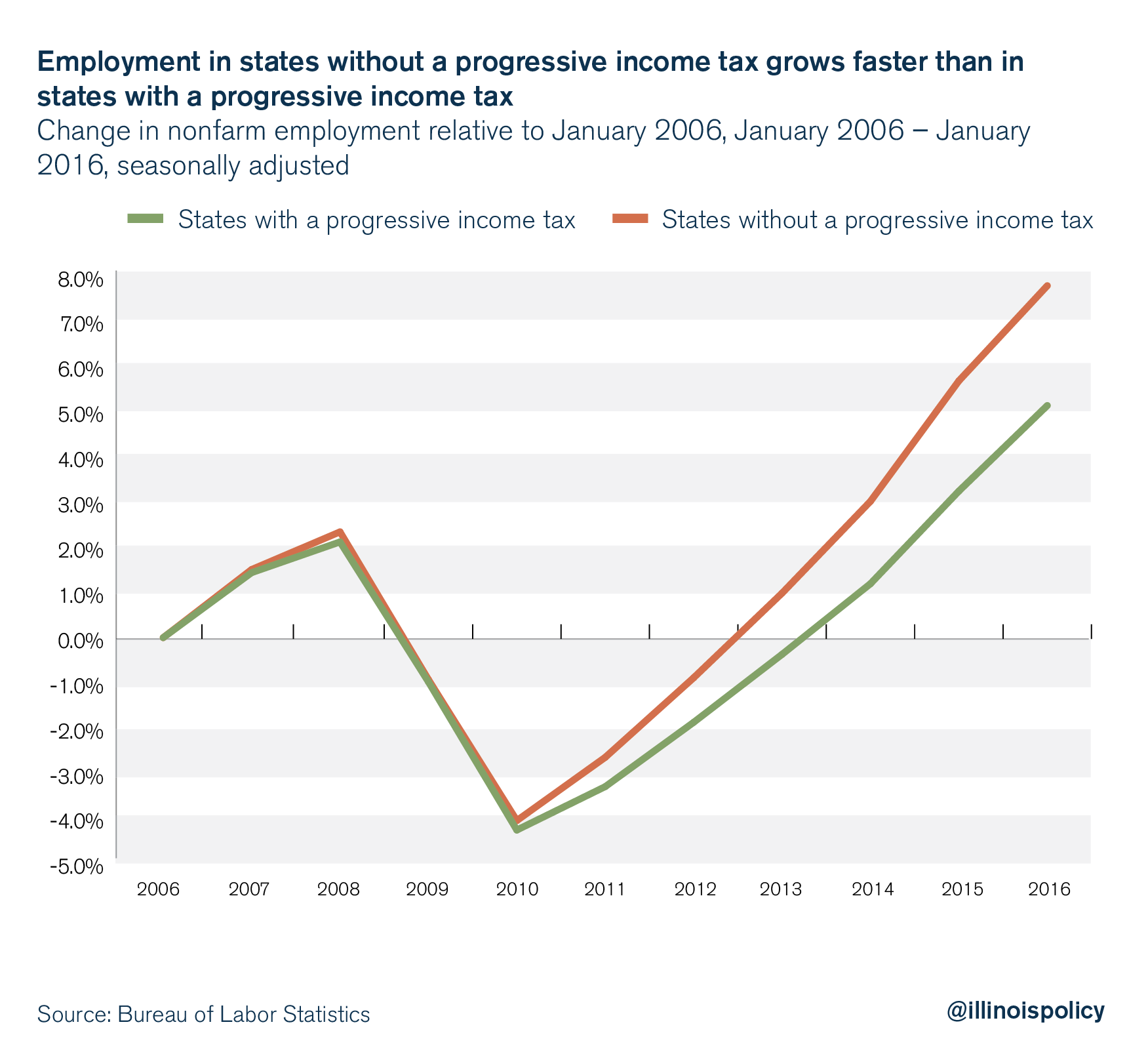

Additionally, employment has increased faster in states without progressive income taxes. In states without a progressive income tax, nonfarm payrolls have increased 7.8 percent since 2006, while payrolls have only increased 5.1 percent in states with a progressive income tax.

Finally, wages and salaries have been growing faster in states without a progressive income tax. Since 2006, states without a progressive income tax have seen wages and salaries increase 15.3 percent compared to 12.6 percent in progressive tax states.

Illinois already lags the nation and neighboring states on key metrics of economic growth, including: jobs growth, new business creation and personal income growth. Income growth is tied for the worst in the nation from 2007 to 2018. The Prairie State’s economy simply cannot afford to be dragged down by more bad policy from Springfield.

Myth #5: A progressive tax will help fight income inequality

Reality: States with progressive taxes have higher inequality and it is growing faster

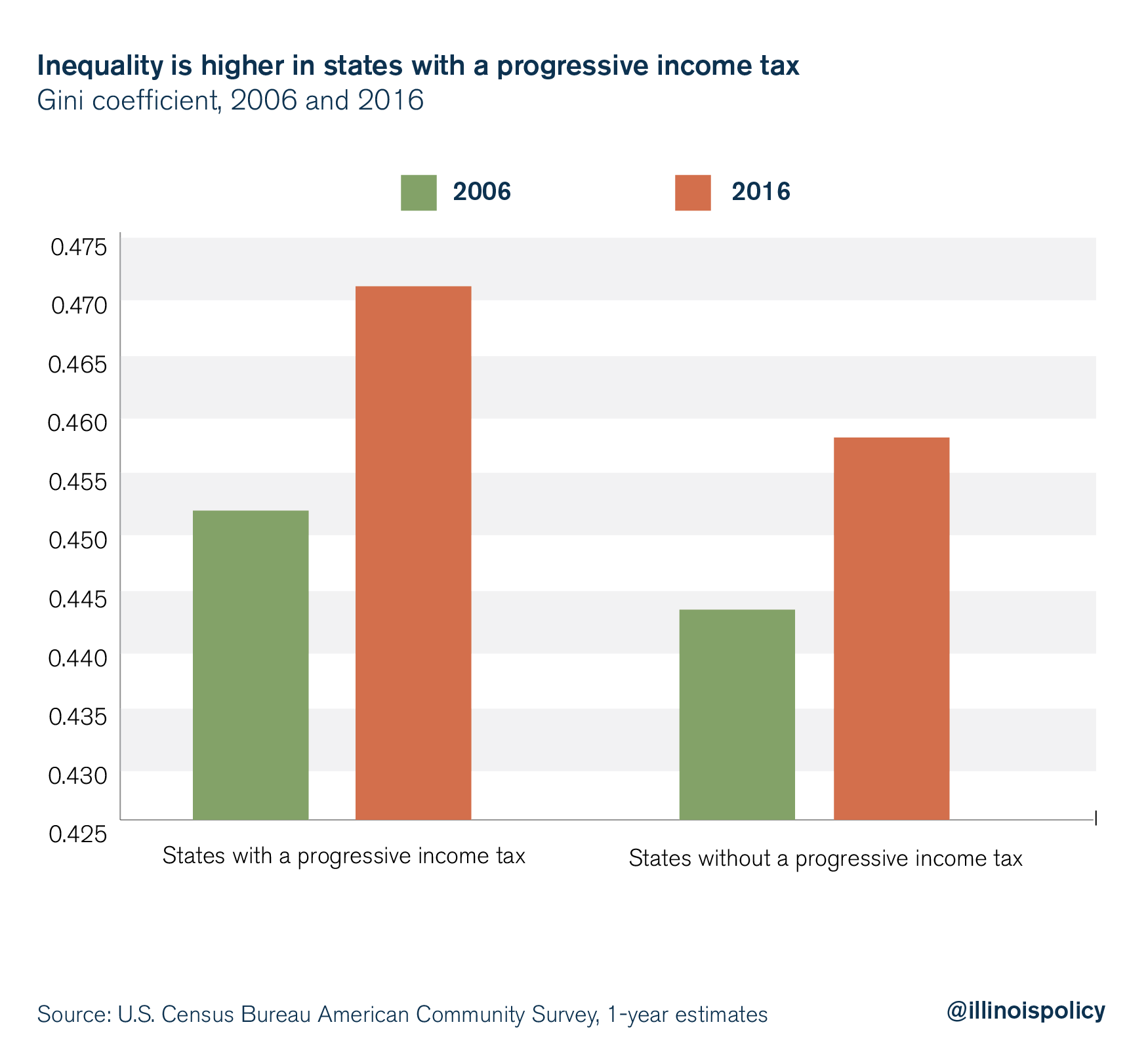

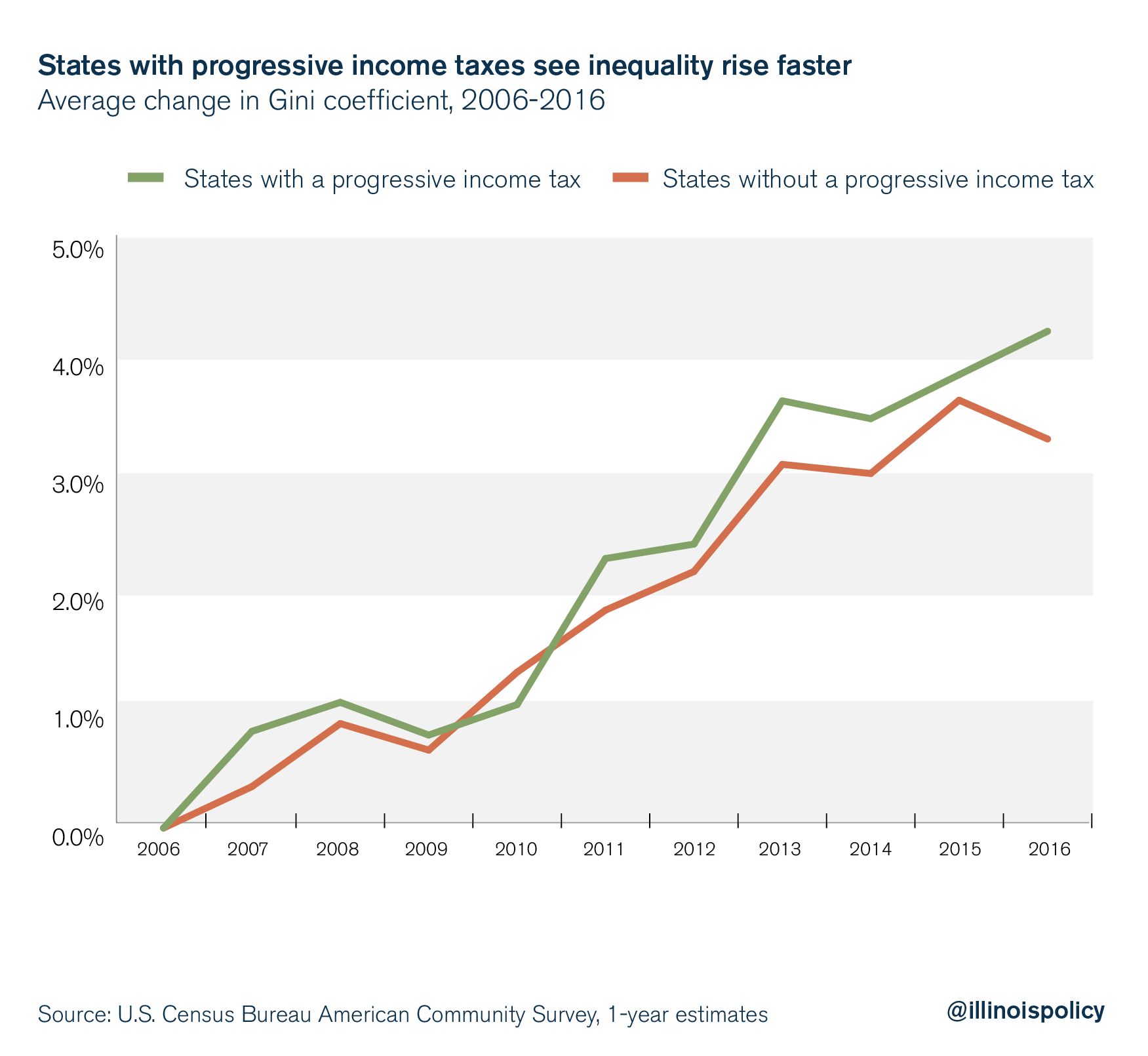

The most popular measure of income inequality, the Gini coefficient – which measures the gap in incomes between different segments of the population – shows that inequality in states with progressive taxation is both higher on a static basis and growing faster over time.

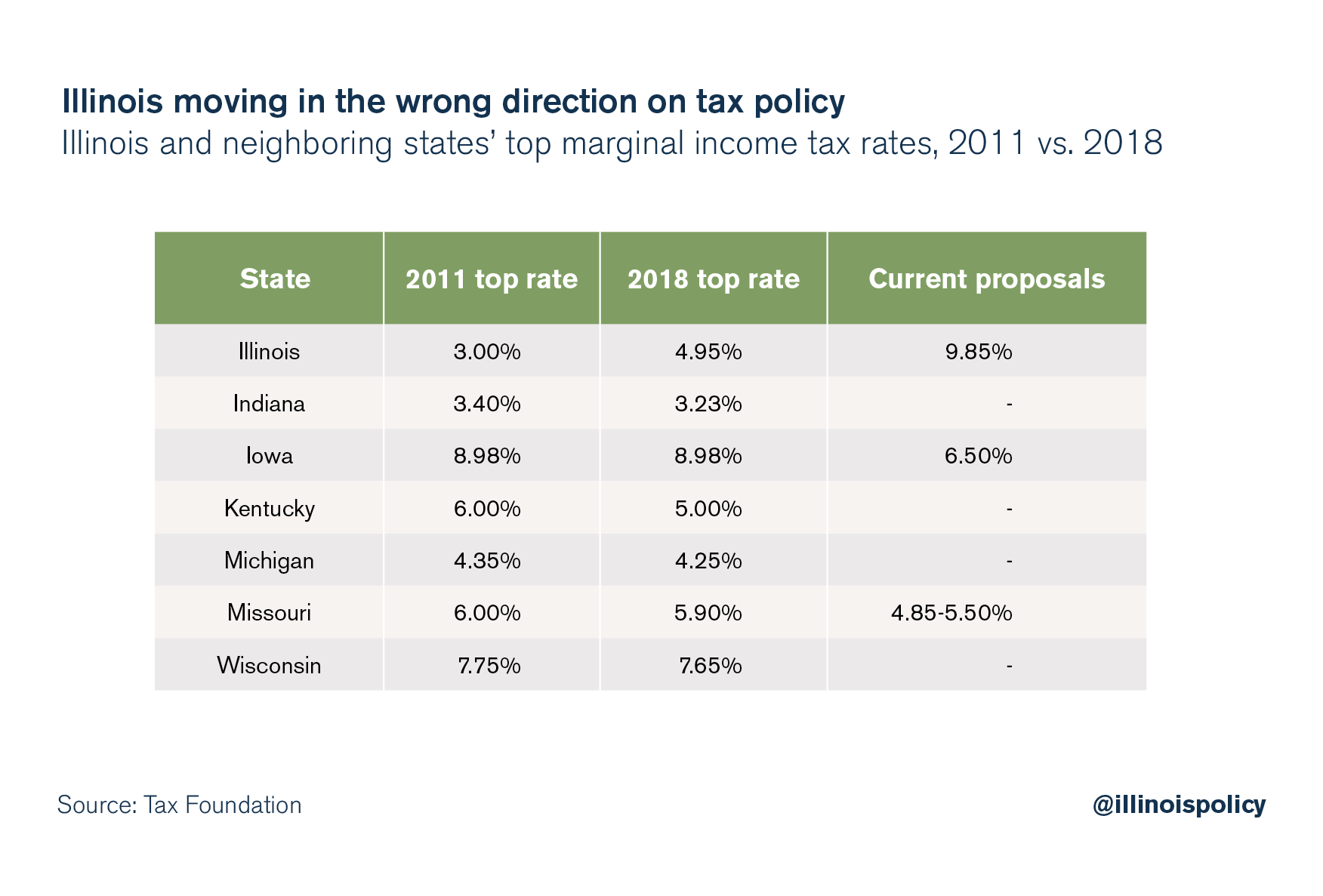

Myth #6: Illinois’ flat tax makes it an outdated outlier given that most other states have progressive taxes

Reality: Other states are reducing their income taxes; Illinois is an outlier in contemplating increasing them

As mentioned earlier, seven states have no personal income tax at all. An additional two states, Tennessee and New Hampshire, only have income tax on capital gains.

All neighboring states are moving toward lower income taxes, while Illinois is the only state talking about moving in the opposite direction.

It’s no coincidence that Illinois lost 114,000 residents on net to other states from July 2017 to July 2018, a rate of 313 residents per day. The 2018 Illinois Issues Survey found that 53 percent of residents have considered leaving Illinois. The top reason “why” is the comparatively lower tax burdens in other states, with 39 percent of those who considered leaving citing this as their “primary reason.” Even more middle-class residents have considered leaving, at 64 percent.

The behavior of neighboring states is particularly important because they are more directly competing with Illinois in the regional economy to attract residents and businesses.

Rather than continuing to try to solve Illinois’ fiscal problems with economically harmful tax hikes, Illinois should look to structurally reform spending and provide tax relief.