Black, Hispanic women hit hardest after Illinois decreed which jobs were ‘nonessential’

More than 1 in 5 black and Hispanic female workers in Illinois lost their jobs during the first month of the COVID-19 lockdown.

George Floyd’s murder was a trigger, but to only focus on his death or the past dozen deaths of black Americans at the hands of law enforcement would be tragically shallow.

The demand from the streets is about very old grievances. America is refusing to accept continued indifference, and Illinois especially must look at how its institutions and public policy decisions have perpetuated injustices.

Illinois just saw the COVID-19 pandemic expose decades of disinvestment in the health of minority communities. Gov. J.B. Pritzker imposed the nation’s strictest lockdown, but rather than save lives it quickly exposed minorities, and especially women, to harsh economic fates expected to take a decade to repair.

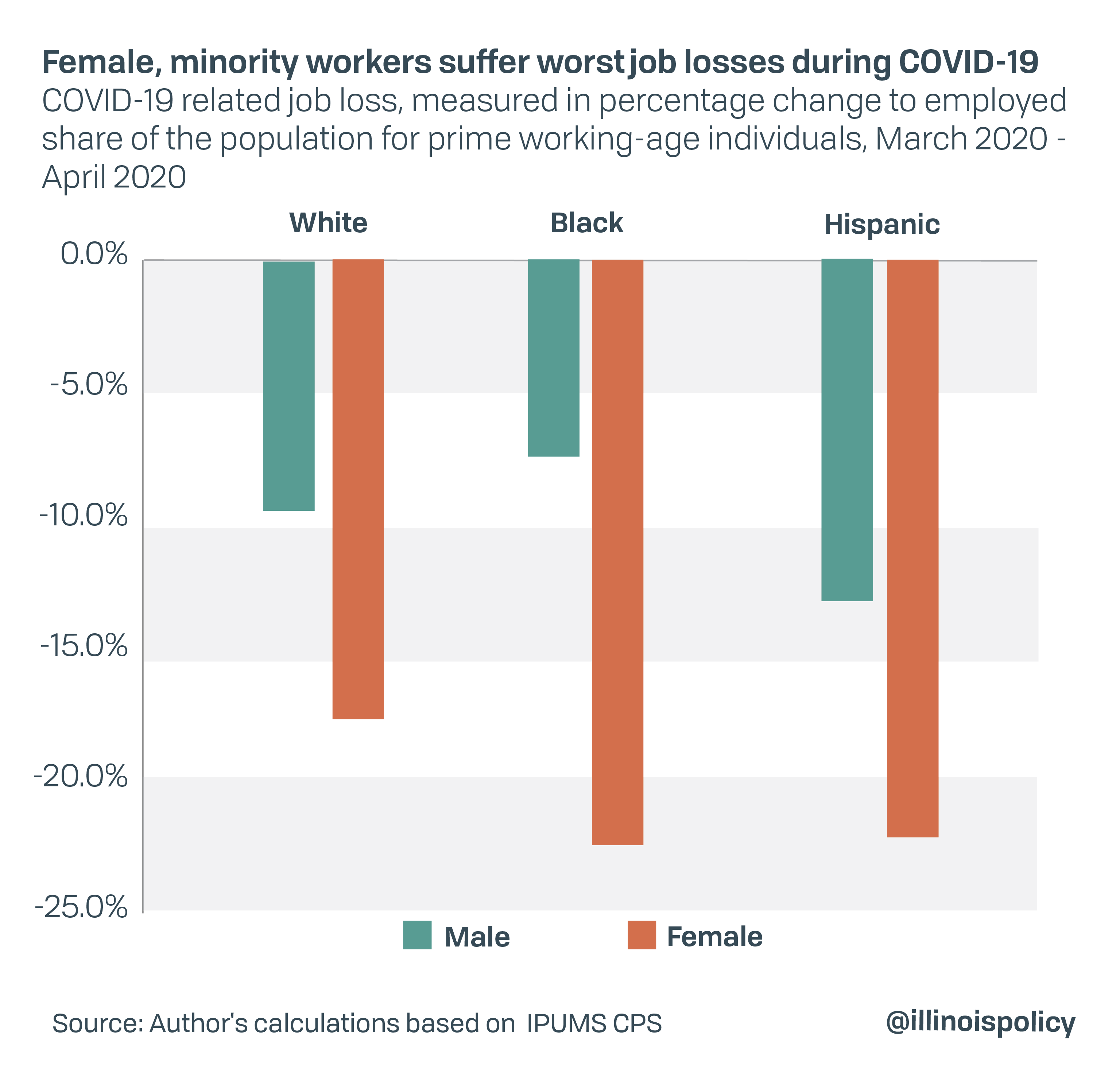

Just how much minority communities lost is starting to be quantified by federal data. Minority workers were disproportionately hurt, with women losing the greatest share of jobs across all ethnicities, just during the first month after Pritzker declared whose jobs were essential.

Job losses among women were the worst for black females (22.4% drop in employment) and Hispanic females (22.1% drop), while white females saw a 17.6% drop in employment from mid-March to mid-April due to COVID-19 and the measures taken to contain the virus. More recent data shows over 1.15 million Illinoisans idled from when the coronavirus hit in mid-March through May 23.

Men also suffered heavy job losses during the first month, but to a lesser extent.

Hispanic men in Illinois saw a 13.1% drop in employment, while white men saw a 9.7% drop and black men saw a 7.5% drop during the first month of Illinois’ shutdown.

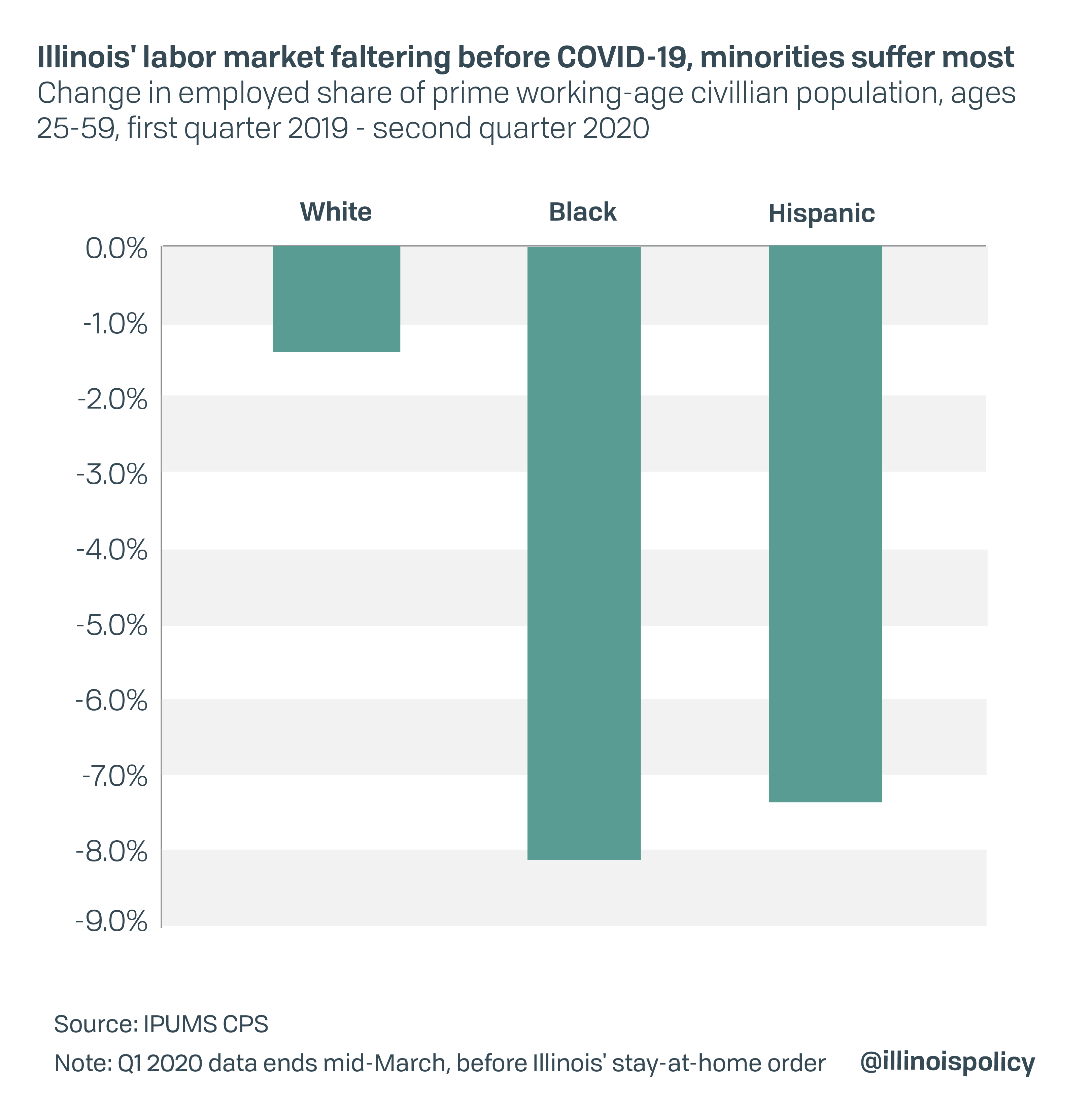

While the lockdown on the surface appears to have affected black men to a lesser extent, this is only because black Illinoisans suffered the heaviest job losses in the lead-up to the economic downturn, prior to Illinois’ stay-at-home order. Employment fell by more than 8% in the year prior to the crisis, bringing employment rates for the black community to the lowest level of any racial or ethnic group in Illinois.

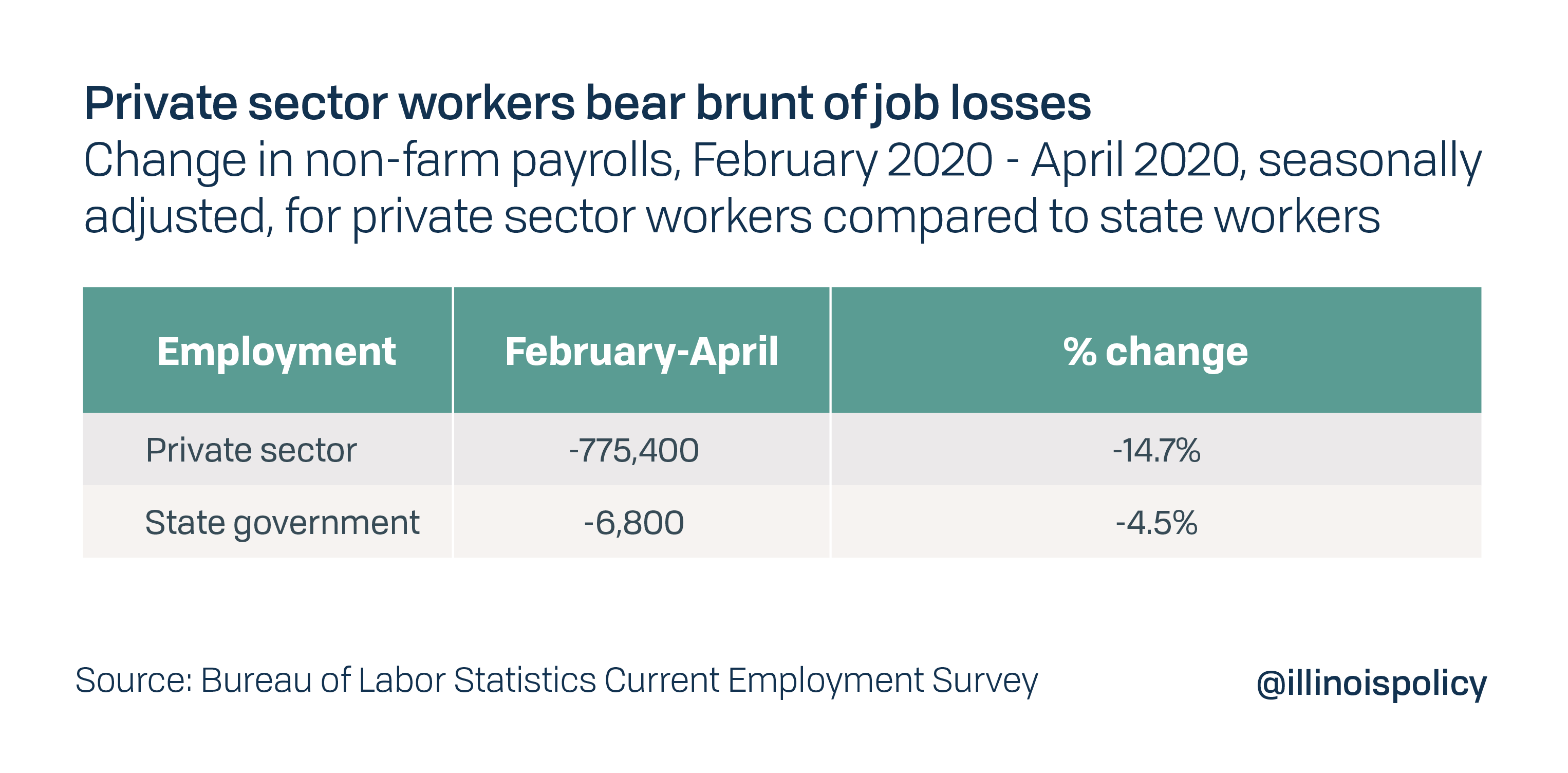

So far, private sector workers have borne the brunt of job losses in Illinois, while the ranks of public sector employees have been largely shielded from the downturn. In fact, thousands of Illinois state workers are set to receive pay raises on July 1.

Unfortunately, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to damage Illinois’ private sector, pre-existing gender and racial economic and health gaps are also being amplified.

In Illinois and across the U.S., black people have suffered both higher hospitalization and fatality rates from the virus, as well as more severe financial harm from the economic crisis. A new report from ProPublica Illinois shows deaths in the black community can be attributed directly to decades of disinvestment in black neighborhoods, and poorer health associated with fewer economic opportunities.

The evidence suggests female workers, black workers and Hispanic workers are more likely to work in jobs that can’t be performed at home. Despite the fact that some female workers are on the front lines, many others were among the first to lose their jobs at the start of the pandemic.

Protecting essential workers from the virus by following recommendations from public health officials, such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, coupled with a sequential lift of lockdown measures that removed restrictions on low hospitalization-risk, healthy workers, could have mitigated the damage caused by COVID-19 in Illinois.

Private sector job losses have harmed female workers more than males

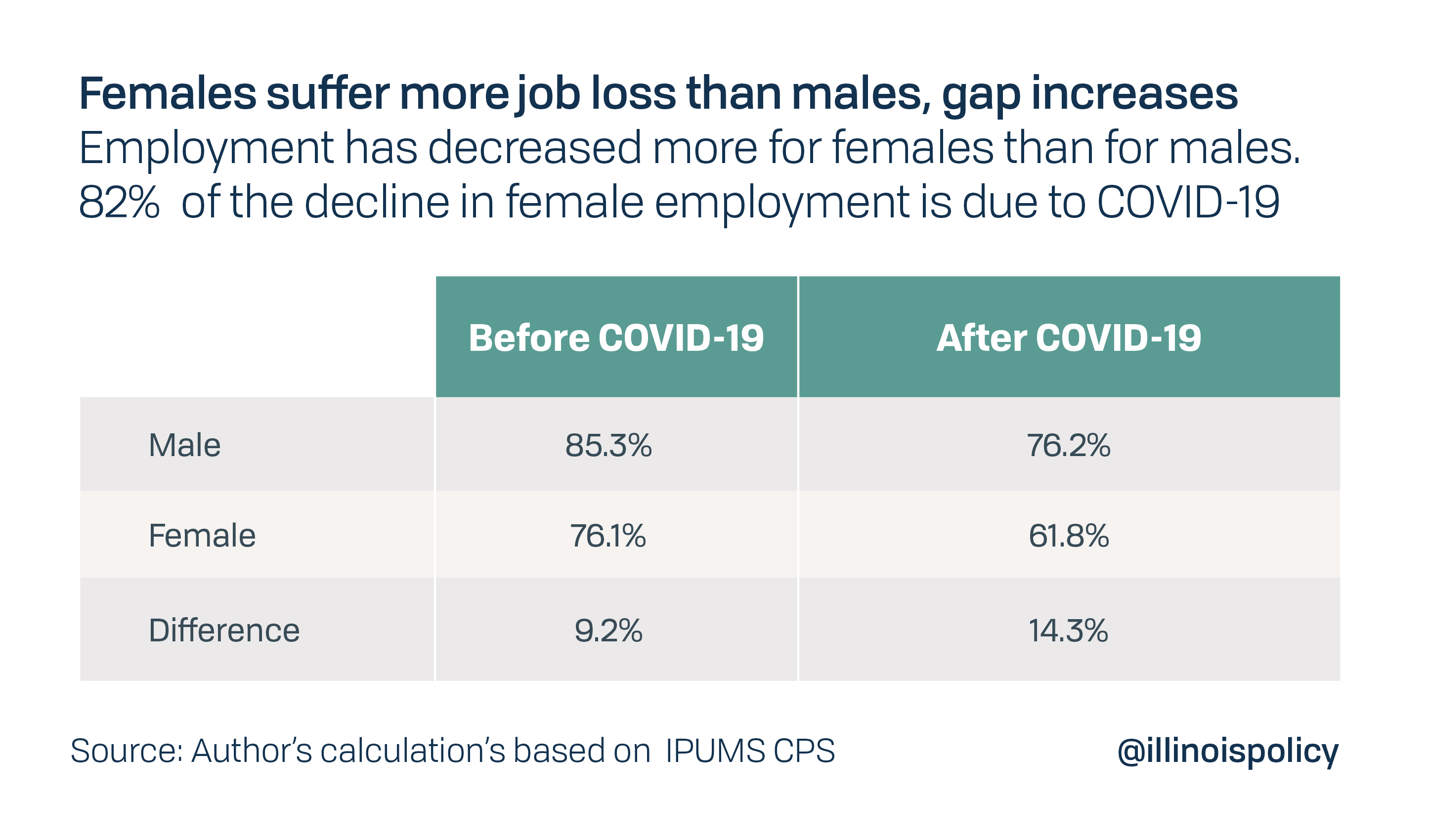

April data from IPUMS CPS shows female workers have suffered the most job losses since the COVID-19 lockdown.

The Current Population Survey, or CPS, is a monthly U.S. household survey conducted jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. IPUMS CPS is an integrated set of data from the CPS from 1962 forward.

Compared to the months before the COVID-19 lockdown this year, employment has decreased more for females than for males, especially for black and Hispanic females.

This is because a large share of females in Illinois held jobs that were deemed “non-essential” by the governor and were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, including retail salespersons and workers in the leisure and hospitality industry. Black and Hispanic females suffered the largest decline in employment (see appendix). This is despite the fact that nearly 1 in 5 black females in Illinois are frontline workers, such as registered nurses, nurse assistants and health aides.

Minorities suffered from weakened labor market prior to COVID-19-related downturn

From the first quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of this year (the data for Q1 ends in mid-March, prior to the state’s stay-at-home order) Illinois’ labor market was already beginning to falter.

Employment for the prime working-age population had already fallen by 1.4% for white Illinois workers, while the decline was nearly 4.5 times worse (-7.4%) for Hispanic workers and nearly 5 times worse (-8.1%) for black workers.

Even among those without a college degree, job loss for black workers was double that of Hispanic workers and nearly 3.5 times higher than whites.

Minorities and low-income workers with no college education suffered the most severe decrease in employment

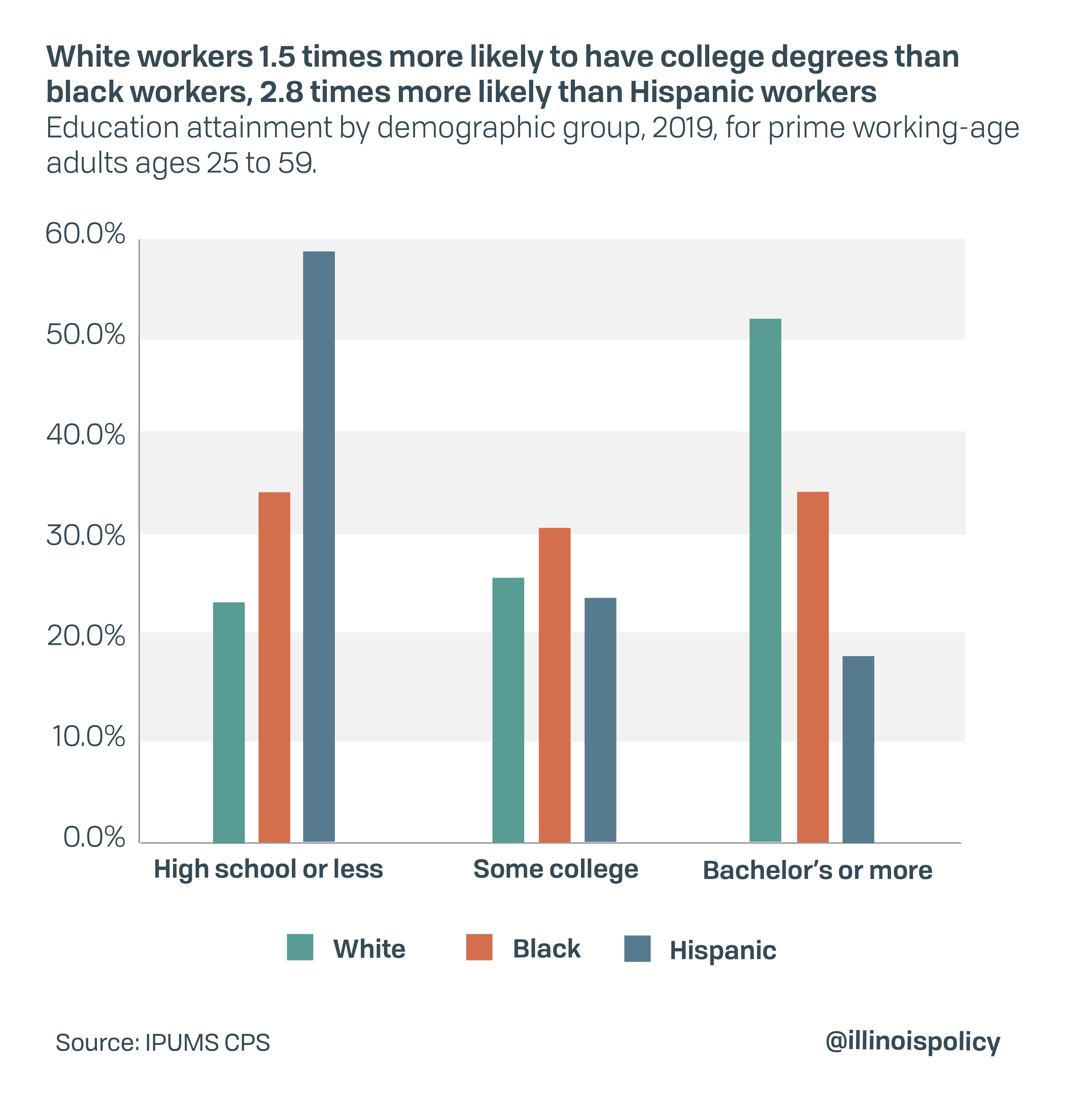

According to work published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, only 37% of U.S. jobs can be performed entirely at home. These tend to be high-paying jobs because they account for 46% of all wages.

Workers who can’t work from home are less likely to be white, have a college degree, or have employer-provided health care. They are also more likely to be in the bottom half of the income distribution.

Economic contractions tend to worsen racial gaps in unemployment

While economists are almost unanimous that a pandemic has serious negative consequences for economic growth, little until now was known about the effects of the U.S. experience with lockdowns used to contain the spread of the disease.

New research published by the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that individuals who live in counties under lockdown are 2.8 percentage points less likely to be employed and have a 1.9 percentage points lower labor-force participation. Lockdowns account for close to 60% of the decline in the employment-to-population ratio.

Furthermore, the COVID-19 lockdowns have a negative impact on future aggregate demand due to a mix of lower expected income, heightened uncertainty and supply-side restrictions.

Four decades of labor market outcomes reveal that even for black and white workers with similar education and work experience, the black-white employment gap tends to increase during economic contractions. This is because black workers tend to get fired first as economic activity weakens.

The newest data suggests that compared to white workers, black employees suffered less job loss than in previous recessions while Hispanic workers were hit disproportionately harder by the COVID-19-induced job losses. This is because in a pandemic, a worker’s occupation really matters.

A new paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research shows workers in jobs deemed “non-essential” lost jobs at a higher rate than other workers.

State governors deemed some jobs “essential” while others were considered “non-essential.” That decision disproportionately harmed the livelihoods of many women and minorities.

Worst of all, research shows the lockdown instituted to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus will have long-lasting negative effects on these populations. This is because many workers often need years to find stable jobs.

Unemployment leads to poor physical and mental health

Black Americans are dying from COVID-19 at a disproportionately high rate in cities across the nation. A report from ProPublica Illinois shows that in Illinois, these deaths can be attributed directly to decades of disinvestment in black neighborhoods, and poorer health associated with fewer economic opportunities.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19-related economic crisis is also likely to exacerbate this problem. This is because the bulk of evidence suggests unemployment leads to poor physical and mental health.

Research shows unemployed workers are more likely than employed workers to develop stress-related conditions such as stroke, heart disease or arthritis.

The fact that saving livelihoods saves lives cannot be understated. It should be part of the public health policy discussion.

Saving lives and reviving the economy go hand-in-hand

The evidence suggests that most small businesses have less than two months of cash on hand while the median small enterprise has more than $10,000 in monthly bills and less than one month of cash on hand. Illinois’ small businesses employ the majority of Illinois workers. Allowing businesses to open again is an important step to save lives and livelihoods.

Although lifting a lockdown will not restore economic activity to levels observed before the pandemic, research shows the sequential lift of a lockdown is the best way to mitigate both the human cost of the virus and the economic damage.

Further, Illinois voters need to consider the effects of the tax hike state leaders are seeking Nov. 3. Economists argue against increasing taxes during a recession. A progressive tax will increase taxes up to 47% on more than 100,000 small businesses just as they are trying to recover from the COVID-19 economic damage, and those small businesses are responsible for the vast majority of new jobs in Illinois.

Illinois families cannot afford to be out of work for an extended period of time. Many are still waiting to have their unemployment claims processed and have little to no savings to feed their families or cover other expenses. Other countries and other U.S. states are beginning to phase in the re-opening of their economies.

A safe return to work for Illinois families is the first step to tackle growing racial gaps and to revive the Illinois economy. A tax increase would be a misstep.

After more than a century of protests erupting in Illinois and across the country, historians consistently peel back the triggers and factors to find economic injustice at the core. Ignoring the disproportionate costs of a pandemic and the pain in the streets by continuing the same, failed policies is to welcome further human suffering.