5 solutions for Illinois schools to fight literacy crisis

The first three years of elementary school are critical in building reading skills so a student succeeds in school and life. Illinois lawmakers can push five proven literacy reforms to give the state’s students a better start.

There is a literacy crisis in Illinois, and it threatens the futures of Illinois’ children – but it can be fixed. Proven reforms used by other states can be promoted by Illinois lawmakers and embraced by local school districts.

Illinois should focus efforts on investing in and improving literacy education for students in the first through third grades using these five literacy solutions based on proven reforms from Mississippi, Florida and Colorado:

- Provide an early universal reading screening for every student in first through third grades to identify reading deficiencies.

- Provide reading interventions for any student in first through third grades with a reading deficiency.

- Notify parents and keep them engaged in their student’s reading deficiency diagnosis and intervention.

- Ensure schools use science-based instruction methods to teach reading.

- Discuss and determine grade promotion decisions with parents and teachers for students whose reading deficiencies are not remedied by the end of the school year.

The first years of school are critical years during which students must build a firm foundation of literacy skills to become strong readers so they can develop into strong learners. Research shows students who fall behind in reading skills, especially in lower elementary grade levels, drop out at much higher rates than their classmates. A student’s likelihood to graduate high school can be predicted by their reading skill at the end of third grade.

This is because students transition from “learning to read” to “reading to learn” from fourth grade onwards. If a student struggles to read at grade level by the end of third grade, up to half of the printed fourth-grade curriculum is incomprehensible.

That’s bad news for Illinois. In 2024, just 31% of Illinois third-grade students met or exceeded reading proficiency standards on the state’s end-of-year assessment. That means 7 in 10 third graders could not read at grade level. Illinois students’ performance on the most recent national reading assessment revealed similar struggles: just 33% of fourth graders met grade-level reading proficiency standards in 2022.

Illinois students are struggling, and reforms are needed to ensure students receive the instruction and support they need to thrive.

States such as Mississippi, Florida and Colorado offer models for Illinois to reverse the low reading proficiency rates plaguing the state’s children. Their solutions can ensure Illinois students are well equipped for success through high school graduation and beyond.

Illinois should focus on investing in and improving literacy education for students in first through third grade using the following five literacy solutions based on the proven reforms undertaken by the three states.

Illinois is part of a national early literacy epidemic

Illinois ranked 17th in the U.S. for the percentage of fourth graders at or above proficiency in reading on the most recent National Assessment of Educational Progress in 2022.

Only 33% of Illinois fourth graders could read at or above grade level. Illinois joined 34 other states and the District of Colombia with just 1 in 3 (or fewer) students reading proficiently.

State-based assessments show similar results. Illinois uses Common Core State Standards for English language arts on the state Illinois Assessment of Readiness. Reading standards are separated into three focus areas: literature, informational text and foundational skills.

Students’ skills in those areas are the building blocks for success later on, but many Illinois third-grade students are not proficient. Just 31% of Illinois third-grade students met or exceeded reading proficiency standards on the state assessment in 2024. Third-grade students recorded the lowest percentage of students able to read at grade level compared to every other Illinois grade level tested in 2024.

The statistics are even worse among Illinois’ minority and low-income students. Only 15% of Black third graders and 19% of Hispanic third graders read at grade level on the state test in 2024. Only 18% of low-income third graders reached proficiency.

Literacy legislation passed in Illinois in 2023 lacked meaningful reform

Lawmakers recognized the poor state of reading proficiency in Illinois and amended the Illinois School Code in July 2023 to create the “State Literacy Plan.”

Local boards of education have control over most curriculum and other policy decisions in Illinois, so lawmakers did not mandate that schools implement the literacy plan or dictate other statewide procedures. Instead, it left local decision-makers to determine what is best for their districts. The plan includes guidance for school districts on core, evidence-based instructional practices in different grade levels, but it does not mandate districts develop curriculum to align with evidence-based literacy components.

Lawmakers did not amend the school code to mandate schools or school districts follow or implement the plan’s best literacy instruction practices. The board’s plan emphasizes flexibility and local autonomy to allow “district-specific adaptations” and for districts to “design local assessment strategies and allocate resources based on their unique demographics and context supported by data and current evidence-based instructional practices.”

While the literacy plan offers helpful guidance to Illinois public school districts, more is needed. The current law lacks the meaningful reform which the following five literacy policy solutions could provide.

A roadmap to reform

With the staggering rates of early learners struggling to read across the country, many states have passed legislation to align reading instruction with evidence-based practices to improve the literacy and academic achievement of students. These evidence-based practices are called the “science of reading.”

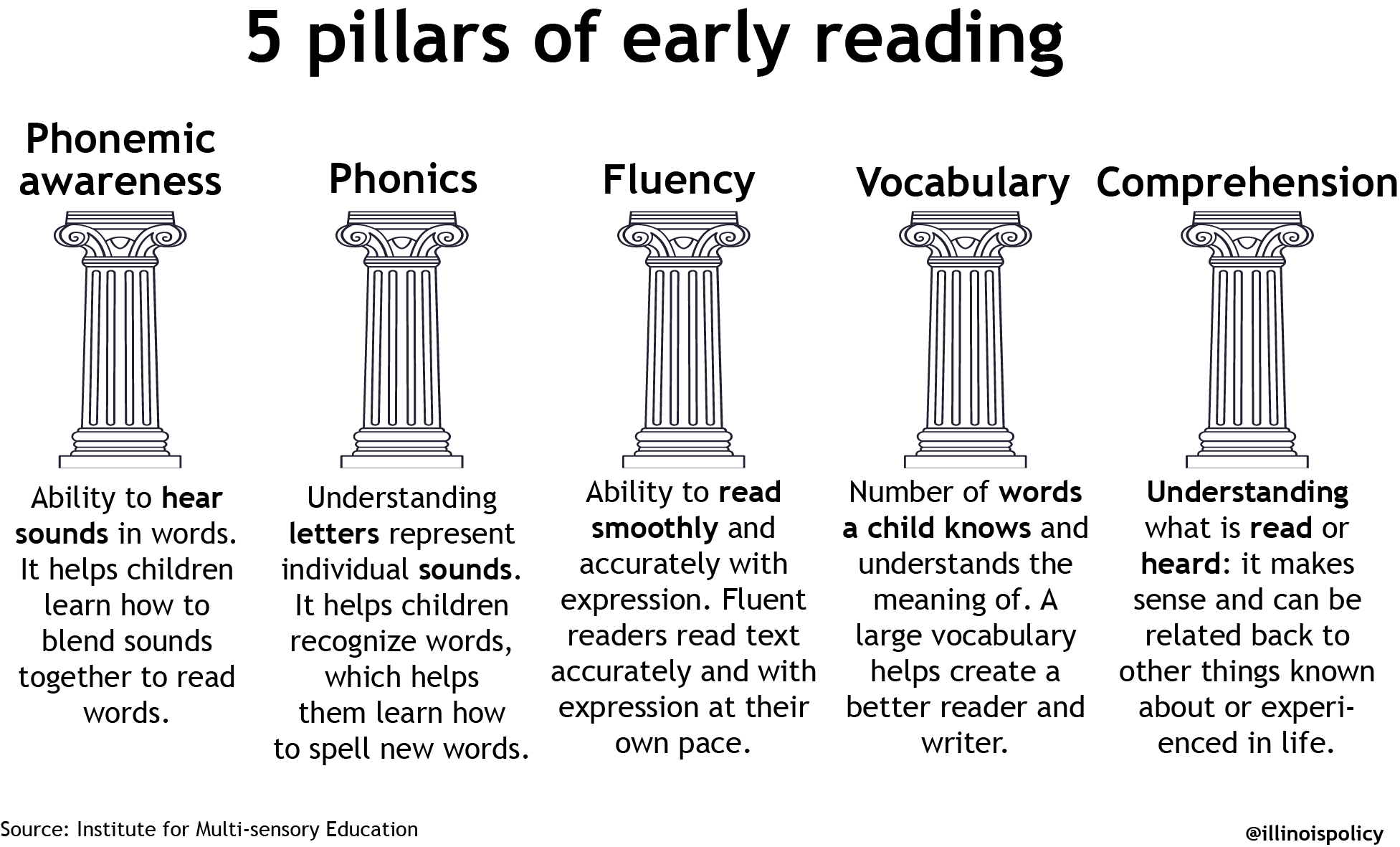

A federally funded report by the National Reading Panel in 2000 first outlined five essential components of effective reading instruction as the basis for the science of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary development and reading comprehension.

According to Education Week, 40 states and the District of Columbia have enacted legislation since 2013 concerning evidence-based methods to teach students how to read. Thirty-four of the states and D.C. have enacted science-based reading legislation since 2020.

States such as Mississippi, Florida and Colorado offer examples for how to exert concerted efforts to improve literacy for students.

Illinois lawmakers and school districts should implement the following five policy recommendations to ensure every Illinois child has access to quality literacy instruction and support.

1. Provide an early universal reading screening for every student in first through third grades to identify reading deficiencies.

Schools need to find reading problems early in elementary years so they can help struggling students catch up to their grade by year’s end.

School districts should administer a universal screening assessment for first through third graders within the first 60 days of the school year to identify students with a possible reading deficiency. An additional diagnostic reading assessment should be administered within 30 days of the universal screening assessment for any student who displayed a possible reading deficiency to determine the specific reading skills the student lacks.

Illinois’ comprehensive literacy plan created by the state board of education outlined the importance of assessments such as universal screenings, benchmark assessments and diagnostic assessments to support students’ literacy.

Illinois schools aren’t required to provide universal reading skills screenings or diagnostic reading assessments to students. Instead, every public school student in grades 3-8 is required to take the Illinois Assessment of Readiness which provides an end-of-year assessment in both English language arts and mathematics. The assessment measures students’ proficiency at the end of the school year compared to state learning standards.

To better evaluate students, school districts need to develop assessments that more quickly identify students who need additional support in reading instruction.

2. Provide reading interventions for any student in first through third grades with a reading deficiency.

It is vital for schools to provide intensive reading interventions for students who might have reading deficiencies so they meet grade-level reading standards by the end of the school year. Research shows the harms when students do not read proficiently in early grades and continue to fall farther and farther behind in school.

School districts should develop and implement an individualized reading intervention program immediately following a first- through third-grade student being identified as having a reading deficiency.

The reading intervention program should be developed by the student’s school and teacher. The program should provide, at a minimum, one-on-one reading instruction which addresses the five foundational components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary development, reading fluency and oral skills, and reading comprehension.

School districts should equip teachers to continue implementation of a student’s reading intervention program until the student demonstrates grade-level reading competency.

3. Notify parents and keep them engaged in their student’s reading deficiency diagnosis and intervention.

It is important for parents to be engaged in their student’s reading remediation. Studies have shown students do better academically with parents involved. As the Harvard Graduate School of Education reports, “several decades of research points to several benefits of family involvement for children’s learning, including helping children get ready to enter school, promoting their school success and preparing youth for college.”

School districts should notify parents within 10 days if their first- through third-grade student has been identified as having a reading deficiency. Schools should also schedule a meeting with the parents to discuss the specific reading difficulty and the individualized reading intervention program.

The notification and meeting should communicate to parents the research showing reading competency by third grade is a critical milestone, explain their student’s reading deficiency and how the teacher identified the deficiency.

Parents should have access to the individualized reading intervention program once it has been developed by the teacher and school. Parents should be able to work alongside the teacher and school to support reading success.

Schools should continue to keep parents informed about their child’s reading deficiency and the interventions offered with each quarterly progress report until the student is reading proficiently.

4. Ensure schools use science-based instruction methods to teach reading.

School districts should use instructional methods which are rooted in the science of reading and review current instructional materials used for foundational reading skills to ensure they align with the science of reading and do not support “three-cueing.”

Eliminate the use of “three-cueing,” which leans on pictures and context to encourage students to guess at new words. Using this method to teach foundational reading skills has been shown to hinder reading proficiency. Instead, instruction should focus on the five foundational components of reading as identified by the National Reading Panel in 2000: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary development, fluency and comprehension.

As in the Florida experience, schools and teachers may need support on how to tailor instruction to the five foundational components of reading and the science of reading. To that end, the state board of education and school districts should determine ways to support teachers and schools in implementing science-of-reading instruction methods.

5. Discuss and determine grade promotion with parents and teachers for students whose reading deficiencies are not remedied by the end of the school year.

Research shows students need to read well by third grade to succeed later. That’s why many states have implemented policies to retain third graders who are not prepared with the reading skills needed to enter the fourth grade. The decision to promote or retain a struggling student, particularly in the transition from third to fourth grade, should be taken more seriously by Illinois schools.

Illinois school districts should host an end-of-year meeting between the teacher and parent of a first- through third-grade student with a reading deficiency to discuss and decide whether the child will advance to the next grade level.

If a student still struggles to read even with an intervention plan, schools should give written notice to the student’s parents informing them of the deficiency and scheduling a meeting to discuss potential grade-level retention as a reading intervention strategy.

The end-of-year parent meeting should discuss at least the following: the serious implications of entering fourth grade with a reading deficiency, their student’s reading deficiency, if the student can handle next year’s work and the potential effects on the student if they are retained.

The decision to retain or promote a first- or second-grade student should be made by the school, teacher and parent collaboratively, but parents should be given the final say. A written statement with the decision must be given to the parents and to the school district superintendent.

The decision to retain a third-grade student should be made collaboratively, but the state should require the local school district superintendent to approve any decision to advance a third-grade student with a significant reading deficiency.

Local school boards should act now to implement reforms

Illinois local school boards don’t have to wait for state lawmakers to enact needed literacy reforms in their school districts. Local school boards understand their students best and are best suited to ensure their students are well equipped with the reading instruction needed to thrive academically.

Illinois is a local-control state, which means “the governing and management of public schools is largely conducted by elected or appointed representatives serving on governing bodies, such as school boards or school committees, that are located in the communities served by the school,” according to the Great Schools Partnership’s Glossary of Education Reform.

That means local school boards are given significant autonomy over decision making within their districts. According to the Illinois Association of School Boards, “The Illinois Constitution grants boards of education latitude in governing their school districts, subject to state laws and regulations.”

If the state were to adopt the suggested policy reforms, school boards and local school districts would be required to adopt, implement and enforce the literacy policies. But there is nothing stopping local school boards from proactively enacting literacy reforms at the local level.

Each of the reforms suggested can be implemented individually by a local school board, and doing so would make those local communities more attractive to families.

Illinois students are struggling to reach grade-level proficiency in both reading and mathematics. The low rates of literacy among lower elementary students only threaten to worsen Illinois’ proficiency declines.

Only immediate action will prevent Illinois students from falling farther behind.