Illinois tops neighboring states with $10 minimum wage on July 1

Illinois’ second minimum wage increase this year is part of a plan to hit $15 an hour in 2025. Small businesses face tough decisions on cutting staff or raising prices.

After months of COVID-19 restrictions cutting incomes and idling workers, Illinois’ small businesses are bracing for another blow: Illinois’ minimum wage will increase to $10 an hour on July 1.

The raise to $10 is part of the state’s mandate to get to $15 in 2025, signed by Gov. J.B. Pritzker in February 2019. The July bump will be the second this year, after it went to $9.25 on Jan. 1 from $8.25.

Danville, Illinois, lost its Papa Murphy’s and Montana Mike’s restaurants, with both owners blaming the economic fallout from COVID-19 restrictions and the impending minimum wage hike for killing their businesses.

Papa Murphy’s owner Ray Fields posted a sign on his door that read, “the current economic climate and coming state laws have driven this store out of business. We simply cannot keep this store open as costs continue to rise in Illinois,” according to the Commercial-News, the local paper in Danville. The business opened in 2007, surviving the Great Recession, and had 10 to 20 employees.

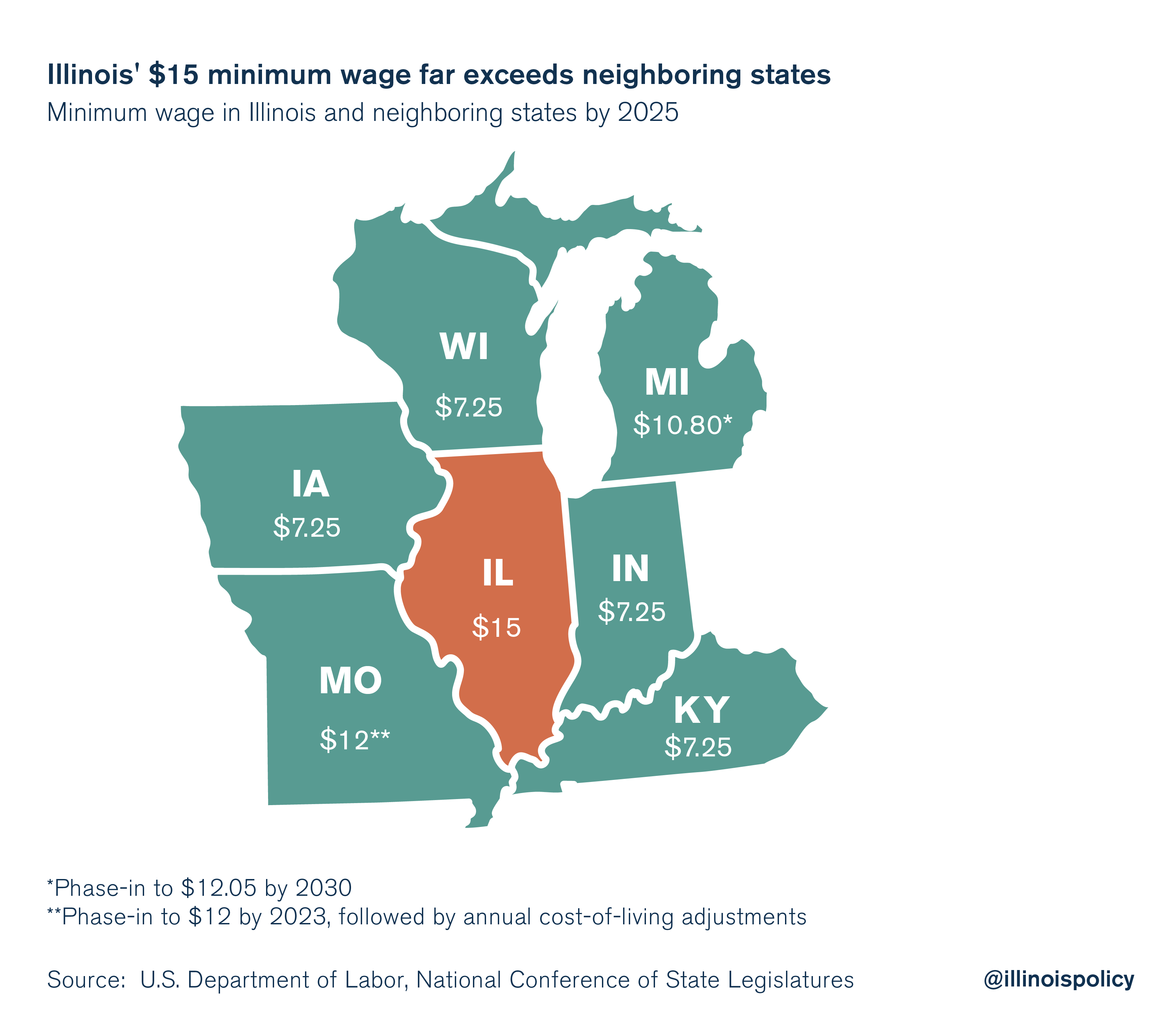

Illinois on July 1 passes Michigan’s $9.25 an hour to be the highest among neighboring states. It will remain ahead of all its neighbors at $15 in 2025.

Melanie McCullough owns Bradford Snack Shack in Bradford, a small town north of Peoria. With a small customer base, the minimum wage increases will put additional pressure on her.

“We are a very small rural town, with 750 people in our whole village,” McCullough said. “Operating this business is a challenge, with the added burden of minimum wage hikes, all the additional taxes that have been implemented and the concern of the possibility of a progressive income tax coming our way.”

If voters Nov. 3 were to remove the Illinois Constitution’s flat tax protection and allow lawmakers greater power to set tax rates, it will raise taxes on over 100,000 small businesses in Illinois by up to 47%. Small businesses were responsible for 60% of Illinois’ job creation since the Great Recession.

Shane Moore, of Hartford, Illinois, was immediately forced to close a division of his vinyl graphics business that printed custom designs on mugs and buttons when the minimum wage increase was passed. He couldn’t afford to keep his six part-time employees paid or move the business a few miles away to Missouri. It was a tough decision.

“People might say those were crap jobs, but they sure as heck mattered to those six people. It paid their car insurance, and their gas, and for college,” Moore said. “Who’s going to pay for those things now?”

In a Facebook post announcing the closure, Moore wrote, “we are frustrated with the lack of oversight of our state leaders and this only hurts area teens and our state’s taxable income.”

Other states have recognized the toll minimum wage hikes will take on small businesses recovering from COVID-19, especially restaurants. California could lose 30% of its 90,000 restaurants without a delay to its January hike, and Virginia is delaying a raise from its current $7.25 an hour.

“While I want to make sure we’re taking care of our workers across Virginia, I also want to make sure we come out of this economic crisis in as strong a position as I can,” said Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam, a Democrat.

The minimum wage increase isn’t a big problem on its own. The larger problem is private demand has fallen. A mandated wage increase that isn’t tied to an increase in productivity will hurt employment and the potential economic recovery.

COVID-19 and the measures to contain it have crippled bars and restaurants more than other businesses. That means less revenue for these struggling businesses and so the mandated cost increase is sure to speed up their demise. Mass business failure would have disastrous consequences for the job prospects of the more than 233,500 Illinoisans in that industry who lost jobs since February.

Even without the increase in labor cost, a national survey in April showed only 30% of restaurant owners expected to survive if the coronavirus crisis lasted four months. At the six-month mark, only 15% expected to be in business.

According to WalletHub, Illinois through Phase 3 had the second-most restrictive lockdown for bars and businesses. Phase 4, with limited inside dining and limits to 25% of bar capacity, began June 26.

Even though lifting the lockdown will not return Illinois to its pre-coronavirus economy, it is an important step in the right direction because 75% of these businesses don’t expect to have the resources to stay in business without some form of public intervention.

The minimum wage hike will also severely impact taxpayers. A memo from Pritzker’s office to WCIA-TV predicted raising the wage to $15 an hour could cost the state $1.1 billion. Local governments will also be incurring higher costs, which would cause property taxes to increase. Property tax rate increases could push many Illinois homeowners into delinquency and foreclosure, acting as a drag on the state’s economy.

The fact that the COVID-19-induced recession has impacted regions of the state differently also means a uniform statewide minimum wage hike that ignores those differences is misguided. Employment outcomes and income are vastly different from Chicago to Carbondale. The Illinois Retail Merchants Association and restaurant owners across the state pleaded for alternatives that take regional differences into account. Unfortunately, the law does not account for the state’s regional cost-of-living differences.

Evidence suggests higher minimum wage levels lead to fewer jobs. This is because wages are already closely linked to productivity. Workers are already paid, in a sense, “what they are worth” to the businesses that employ them. The foregone opportunities disproportionately harm low-wage jobs, which are often the first to decline in response to a rise in the minimum wage.

A 2018 University of Wisconsin, Madison, study on the effects of Minnesota’s 2014 minimum wage hike – which was also phased in over a number of years – offers a recent example of this. In the years immediately following Minnesota’s minimum wage hike, the study found youth employment fell by 9% and service industry employment overall fell by 4%.

Moreover, empirical evidence suggests minimum wages do not elevate low-income families, nor reduce most forms of public assistance.

The stated intention of raising the minimum wage is to increase take-home pay for low-income families. So long as such an increase reduces job creation for those families, it cannot accomplish that goal.

State leaders should be most concerned with Illinois’ economy recovering from COVID-19, because it disproportionately hurt low-wage workers who can take years to find stable jobs. A minimum wage hike adds to their problems finding jobs again.

Then after the COVID-19 threat is diminished, state leaders must reform the public pension systems so those skyrocketing costs stop diverting resources from those who most need them and from priorities that can help grow wages and jobs by growing the economy.