Illinois moves closer to becoming first ‘junk’ state with negative credit outlook

Illinois’ financial outlook was changed from ‘stable’ to ‘negative’ by two major ratings firms, raising the risk the state’s credit rating will formally fall to non-investment grade status.

Two major credit ratings agencies, Standard and Poor’s Global Ratings and Moody’s Investors Service, have dropped Illinois’ credit outlook to “negative” from “stable” on expectations that economic fallout from COVID-19 will strain state budgets.

Both currently rank Illinois bonds just one notch above non-investment grade debt, also known as “junk” status, while the third major agency, Fitch Ratings, puts Illinois slightly higher at two grades above junk. The Prairie State has the lowest rating among states across all three agencies.

A change in credit outlook is not the same as a credit downgrade but reflects risk the state’s rating will drop in the future. A sharp economic downturn will cause revenues to come in billions below expectations at the same time spending automatically increases on pensions and Medicaid, potentially blowing a hole in the budget of $6.3 billion or more, depending on severity.

Illinois’ credit rating and outlook from both Moody’s and S&P are now exactly the same as at the end of the state’s two-year budget impasse.

The risk of dropping to junk status may be even higher than when the state had no formal budget for two years. According to the Bond Buyer, S&P analyst Geoffrey Buswick said the state now has a “one-in-three” chance of economic conditions deteriorating to a level that would cause its credit to drop to junk. In fact, the state is actually paying higher interest on its debt today than it was in June 2017, according to Crain’s Chicago Business. When investors demand higher interest it generally reflects a higher risk that borrowers will default.

Illinois was the least prepared to weather a recession heading into the coronavirus crisis, with only about 15 minutes of state spending saved in a rainy day fund.

Lower credit ratings mean investors will demand higher interest payments to buy state debt, raising the cost of borrowing to taxpayers. In fiscal year 2020, Illinois will spend almost $2.1 billion on payments for existing bonds or over 5% of the state budget. Fiscally healthy Tennessee will spend just $327 million, or 0.8% of the state’s $40.8 billion budget, on debt service for the coming year.

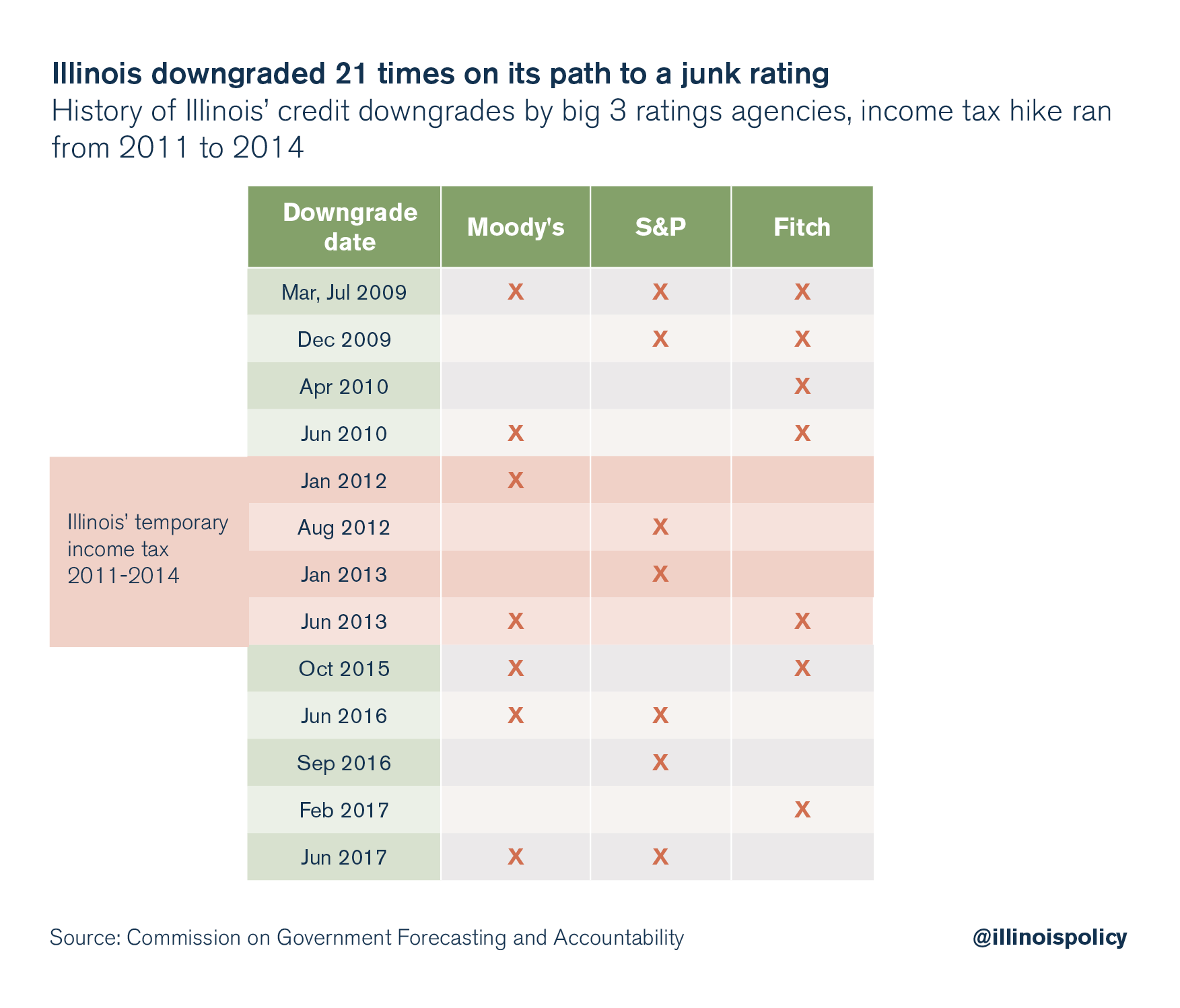

Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation credit has been built during two decades of the state spending more than it brings in, driven primarily by the pension crisis. The state has been downgraded a total of 21 times since 2009.

In 2019, S&P warned that without a “practical reduction in liabilities” of the state pension systems the state’s credit could slip to junk status. Similarly, Moody’s has said Illinois’ rating reflects “extremely large net pension liabilities and a long history of unbalanced financial operations.” The only way for Illinois to reduce pension liabilities is with a constitutional amendment to the state’s pension clause or never-before-seen state bankruptcy, an option not currently authorized by the federal government.

A drop to junk status would shock municipal bond markets nationwide, shaking investor confidence that state and local government debts are a secure investment. Credit ratings are a signal to investors about a borrower’s ability to meet its financial obligations. No U.S. state has defaulted, or failed to make payments, on its bonds since Arkansas in 1933.

Shortly after the start of Great Depression and a series of natural disasters, Arkansas found itself in an impossible financial situation after taking on local road bonds and was unable to make interest payments, The New York Times reports. The state was able to renegotiate payments on outstanding bonds with investors and put itself on a path back to financial health through the Highway Refunding Act, according to The Bond Buyer.

Arkansas never formally entered bankruptcy or received a junk rating, because the state’s initial credit rating from S&P was not until 1966. That means Illinois could be the first on both counts.

To avoid financial calamity, Springfield politicians will need to adopt strategies that fundamentally break with Illinois’ status quo fiscal policy of chasing higher revenues. Tax hikes have been the state’s primary response to financial challenges during the past decade and have objectively failed to lower debt burdens while harming the state’s economy.

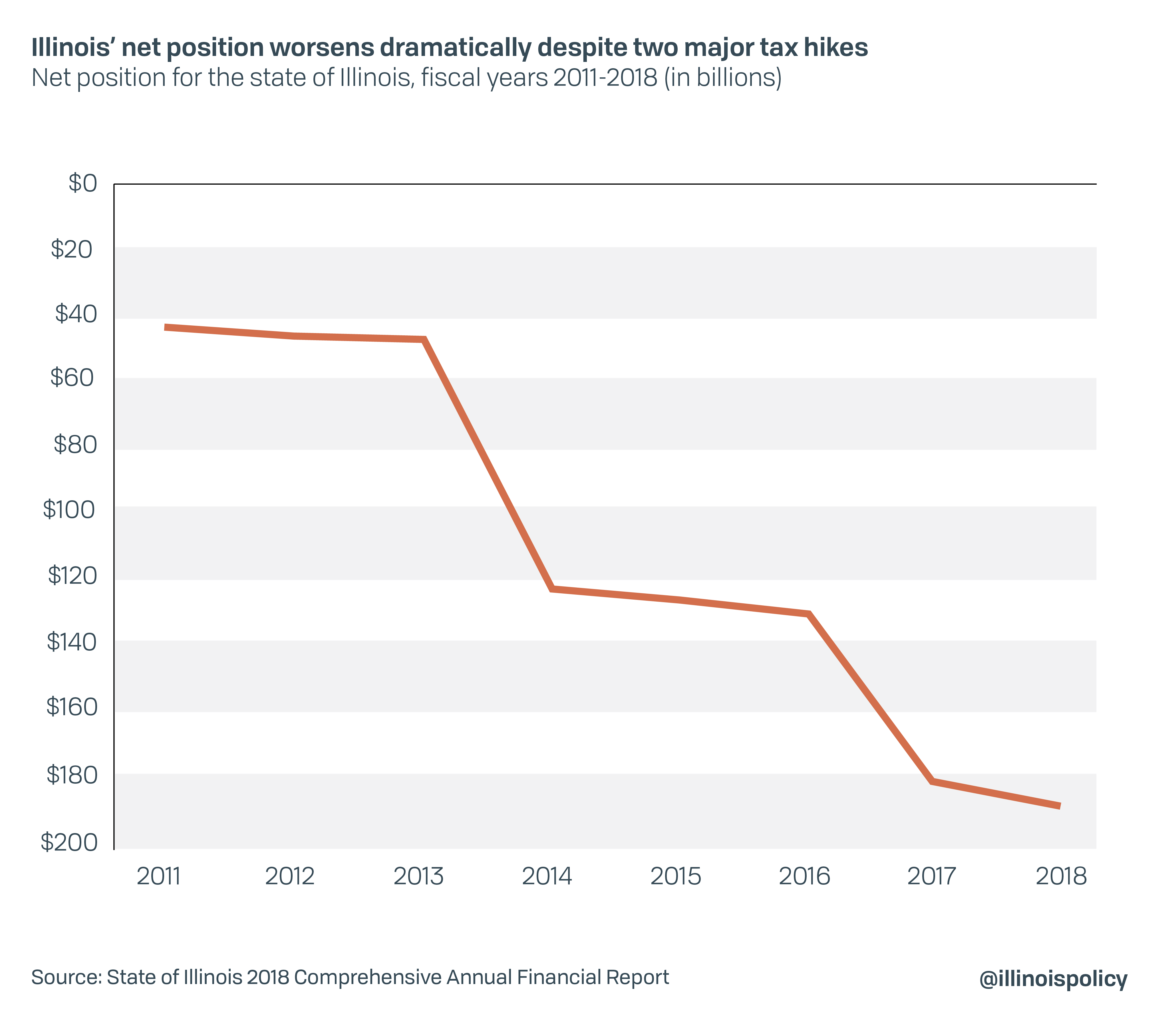

From 2011 to 2018, Illinois’ net debt quadrupled to nearly $190 billion despite a major income tax hike that brought in $37.4 billion in additional revenue from fiscal year 2011 to 2017 and was made permanent thereafter.

Illinois’ history of hiking taxes to pay down debt also helps explain why its economy was faltering even before COVID-19 shut down many businesses, with net job losses in 2019 despite a growing national economy.

Illinois must structurally reform its largest spending drivers, starting with a constitutional amendment to allow pension reform, if it is to have any chance of avoiding junk status, default and bankruptcy. A recent report from the Illinois Policy Institute lays out three commonsense ideas to stabilize finances by reducing debt burdens and spending growth.

By adopting significant financial reforms as soon as possible, elected leaders can shield taxpayers from the prospect of a total financial collapse in state government.