Pritzker’s accounting gimmicks can’t fix pension crisis, but real reform can

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker previously floated a pension plan that included pawning-off state assets, taking on more high-interest debt and reducing pension funding before walking back the plan amid criticism. Here’s a real solution.

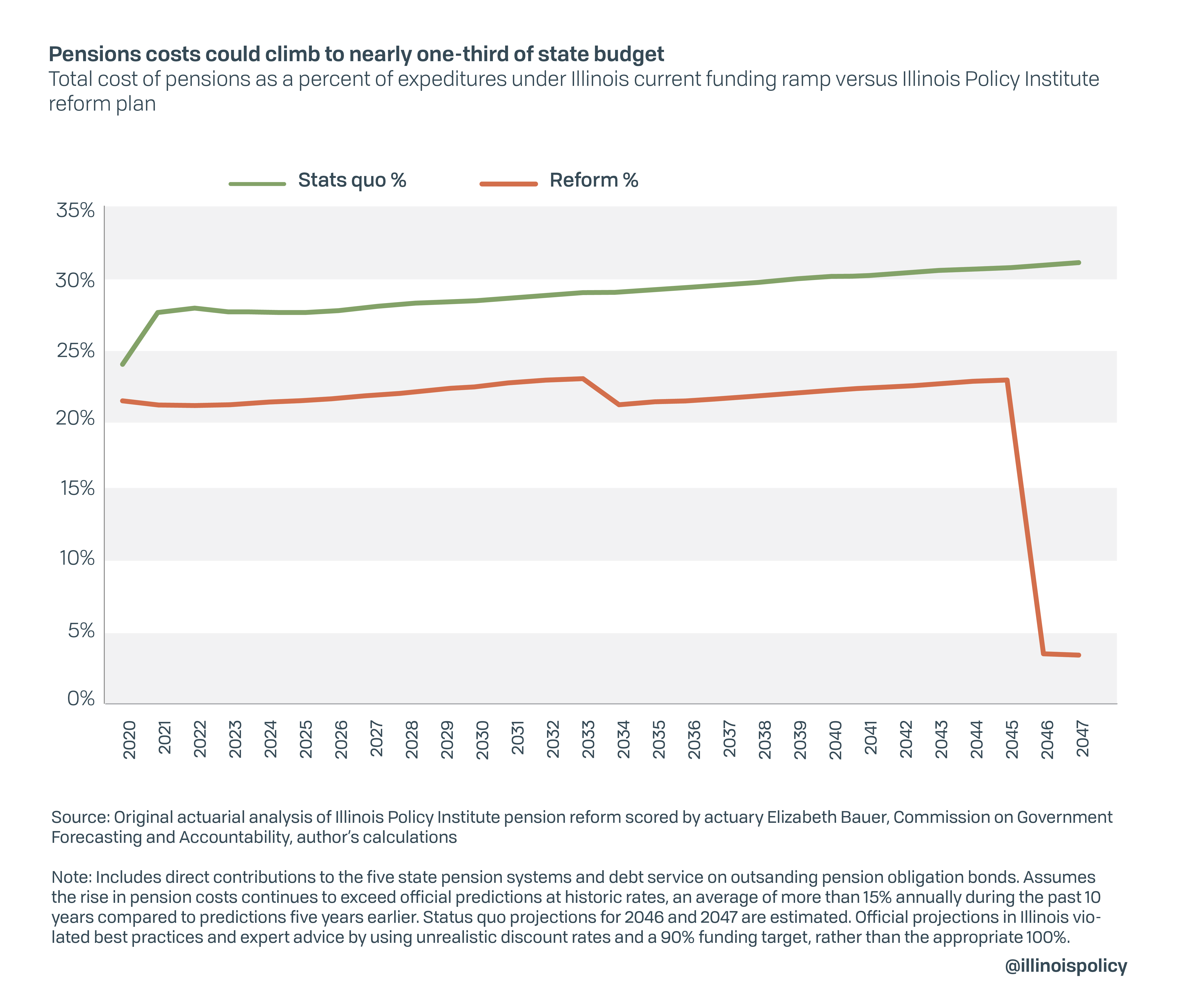

Pension costs consume more than 25% of Illinois’ budget annually, but have historically grown faster than official projections and are on track to grow to nearly 30% of the budget by the end of the decade.

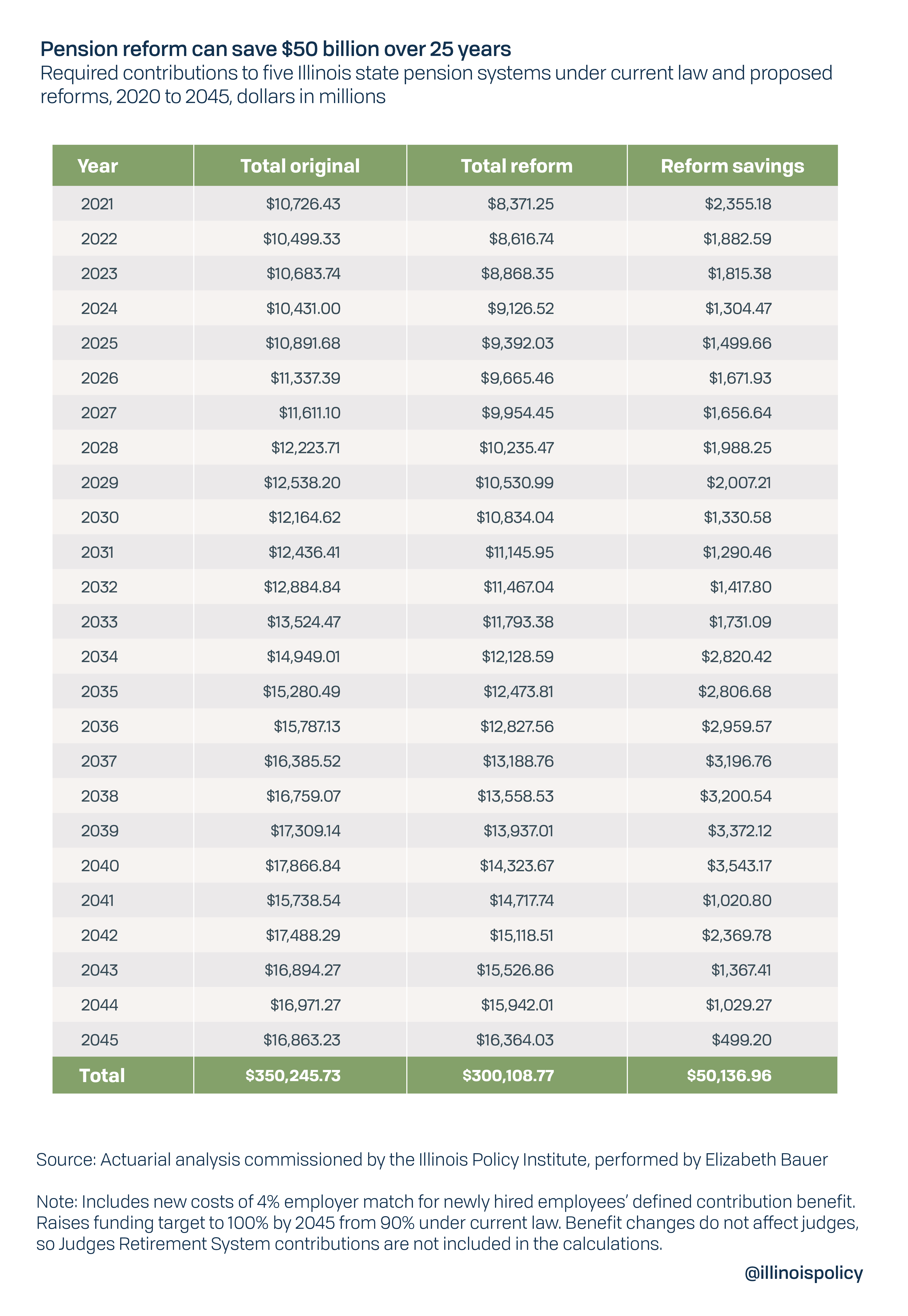

If instead Illinois enacts a constitutional amendment allowing reforms to slow the growth in future pension benefits – without taking away what retirees and current workers have already earned – it could result in an average of $2 billion in budgetary savings during the next 10 years. Savings from now until 2045 would be more than $50 billion. The following year pension costs would fall back to historic single-digit levels as a percent of the budget, because the debt would be fully eliminated.

These are results of an original actuarial analysis of the Illinois Policy Institute’s pension reform proposal, scored by pension expert and Forbes contributor Elizabeth Bauer, an actuary. The plan would raise retirement ages for workers under 45, replace 3% compounding post retirement increases with a measure pegged to inflation and cap the maximum pensionable salary for workers hired before 2011. “Tier 2” workers hired after 2011 already have a pensionable salary cap. The Institute’s reform plan would increase the cost-of-living adjustment for younger workers to full inflation from the current one-half of the consumer price index for urban areas.

Adopting this plan would mean billions more could be spent on debt relief and core government services that have been hollowed out by the rise in pension costs.

Last year Gov. J.B. Pritzker walked away from plans to sell off state assets, gamble with taxpayer money through risky pension bonds and underfund pensions by delaying payments. The $200 million he pledged from his progressive income tax plan represents just 5% of the additional $3.7 billion the tax would take from the economy.

Pritzker’s only remaining options are even larger tax hikes that hit the poor and working class, unwise accounting games or true structural pension reform that starts with a constitutional amendment. Only reform will allow Illinois to truly stabilize its long-running pension crisis.

Does Pritzker still have a plan for the pension crisis?

Illinois’ pension crisis is the worst in the nation, but it’s currently unclear whether Pritzker has a plan to tackle it. The lack of details about pension reform and other fiscal plans in the governor’s state of the state address was criticized by some financial experts.

In his first year in office, Pritzker’s administration had floated a five-point plan to help alleviate the financial pressure of pensions:

- Underfund pensions by extending the payment ramp, shorting pensions by nearly $900 million in the first year and costing the state as much as $105 billion more in the long run.

- Pawn off state property through “asset transfers” and depositing the proceeds into the pension funds.

- Gamble with taxpayer money by adding $2 billion more in risky pension bonds to Illinois’ current debt load.

- Dedicate $200 million from a “progressive income tax,” which voters have yet to approve, to pension funding. That is about 5% of the $3.7 billion more taxpayers would send to Springfield under the tax plan.

- Extend the partial, optional pension buyouts – available to recent retirees and inactive employees – so they are available until 2024 instead of 2021, despite the disappointing first year savings.

Only the last part of this proposal was enacted for Pritzker’s first budget. Pension buyouts saved just $13 million in the first year of implementation, about 3% of the projected $400 million savings. Extending the buyouts for three more years won’t come close to solving the state’s pension debt, which is estimated at $137 billion by the state and at $241 billion by Moody’s Investors Service.

Pritzker walked away from his plan to underfund pension contributions on the payment ramp amid heavy criticism from two major credit rating agencies and the teacher’s pension fund, among others. However, the governor claimed he was able to abandon the plan thanks to an “April Surprise” of $1.5 billion in higher revenue resulting from federal tax reform and faster than expected national economic growth.

The Illinois Department of Revenue raised its projections for income tax revenue by $800 million, almost exactly the amount Pritzker’s proposed budget banked from underfunding pensions. Illinois Comptroller Susana Mendoza cautioned that she could not “confirm nor deny” the unexpectedly higher estimate. Doubts about these projections are part of the reason the Illinois Policy Institute projected the fiscal year 2020 budget was out of balance by between $574 million and $1.3 billion, despite the governor’s claims of balance.

The administration also silently dropped plans for asset transfers and pension obligation bonds, with neither included in the fiscal year 2020 enacted budget. An expected report from a commission on asset transfers has yet to be released. Unfortunately, the governor has indicated that delays in payments on pension debt might still be on the table.

The truth is all of these accounting games cannot come close to solving the pension crisis or freeing up resources for government services and tax relief. As credit rating agency S&P Global Ratings put it, Illinois needs a “practical reduction in liabilities,” which means a reduction in the value of expected future pension benefits.

The only way left to accomplish that is with a constitutional amendment allowing for reductions in the growth of future, not-yet-earned pension benefits. A deeper dive into Pritzker’s original five-point plan shows the proposals range from ineffective to counterproductive.

1. Underfund pensions by extending payment ramp

Pritzker’s first budget proposed reducing pension contributions in the short term by extending the time the state has to pay down the debt to 2052 from 2045. This would have reduced pension funding by $878 million in the first year. However, because Pritzker would be reducing pension costs by simply paying in less, rather than reducing the ‘principle’ of the debt by slowing benefit growth, this would have cost the state roughly $105 billion more in the long run.

In fact, the state’s 90% funding target already violates actuarial best practices. States should seek to pay down 100% of their debt over a period of no more than 20 to 30 years. Any proposal that suggests “re-amortizing” pension debt or “flattening out payments” is nothing but a repetition of past mistakes.

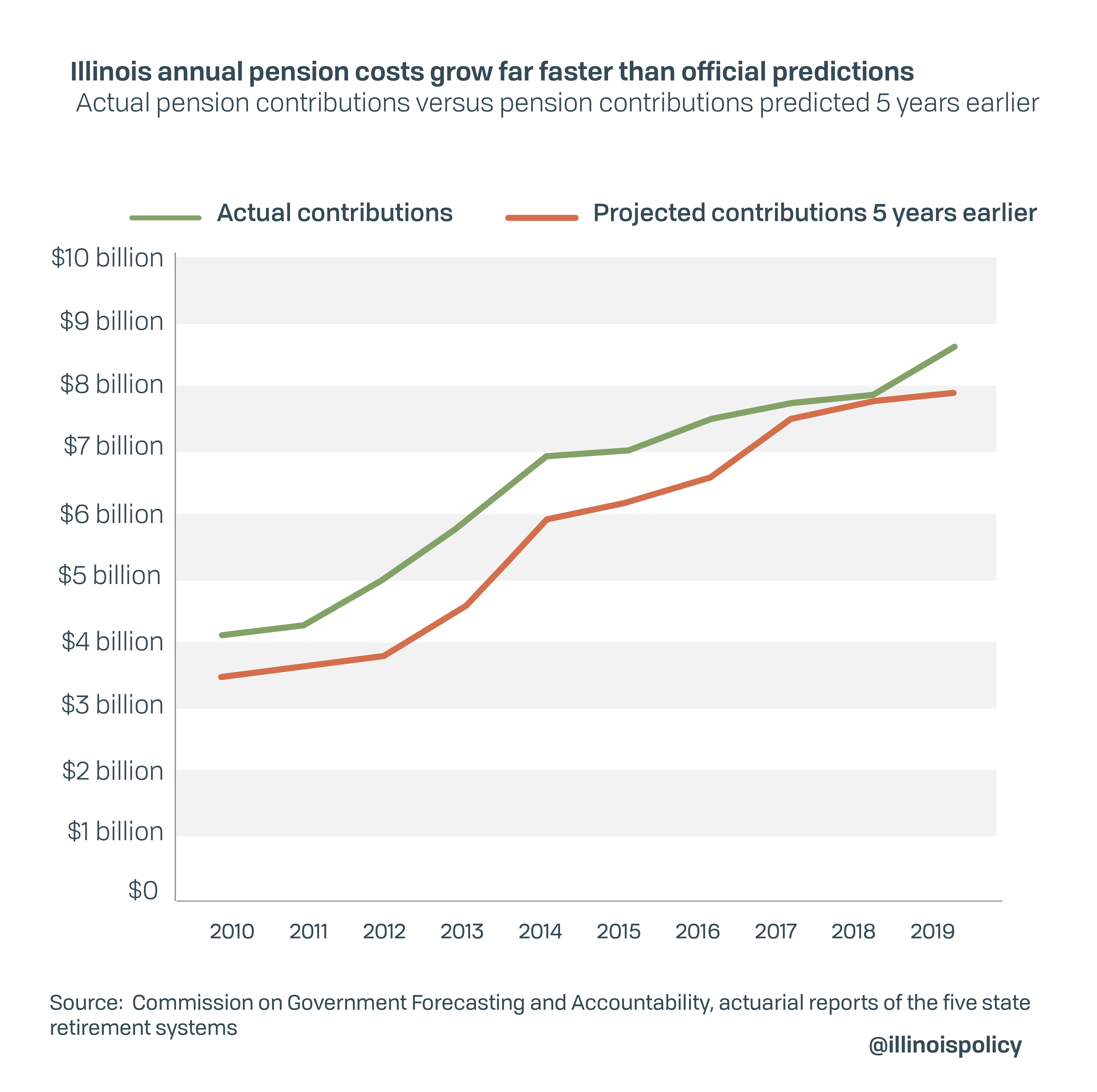

The state’s current unsound funding ramp helps explain why contributions have historically grown far faster than predicted 5-years prior. Pension costs have grown more than 15% faster than official projections over the last 10-years.

Delaying payments and underfunding pensions should not be on the table for any future Illinois budget. Continuing to pursue this proposal would likely mean Pritzker would be the first governor to see his state’s credit rating drop to “junk status.”

2. Pawn off state assets

Pritzker’s administration also suggested raising additional revenue for the pension systems by selling off unspecified state property.

Examples given to the media included “the sale or lease of unused office space” according to Crain’s Chicago Business. Pritzker’s administration never released any data demonstrating the state had a substantial surplus of any type of asset that could be sold to make a dent in the pension crisis.

In fact, Illinois’ net worth is currently negative $189.1 billion, meaning its debts far outweigh its assets. The majority of this imbalance is due to pensions and it’s highly unlikely the state has enough valuable excess assets to materially reduce unfunded pension liabilities.

3. Gamble with taxpayer money

Pension obligation bonds are a gamble with taxpayer money. Pritzker had proposed issuing bonds worth $2 billion.

In theory, pension obligation bonds can save money if the interest on the bonds is lower than the interest earned by the pension funds. This has rarely worked in practice. Citing a history of failure, credit ratings agency S&P Global Ratings considers the use of POBs to be a credit negative. Illinois has already sold nearly $17.5 billion worth of the bonds that will cost $31.3 billion to pay off through 2044.

The only time Illinois should even consider issuing additional pension obligation bonds would be after the enactment of constitutional pension reform. A real reduction in pension costs by reducing liabilities should significantly increase the state’s credit rating and thus lower the cost of borrowing.

Until then, pursuing this idea would be taking a bet which taxpayers are nearly guaranteed to lose.

4. Hike taxes and dedicate an insignificant amount to pensions

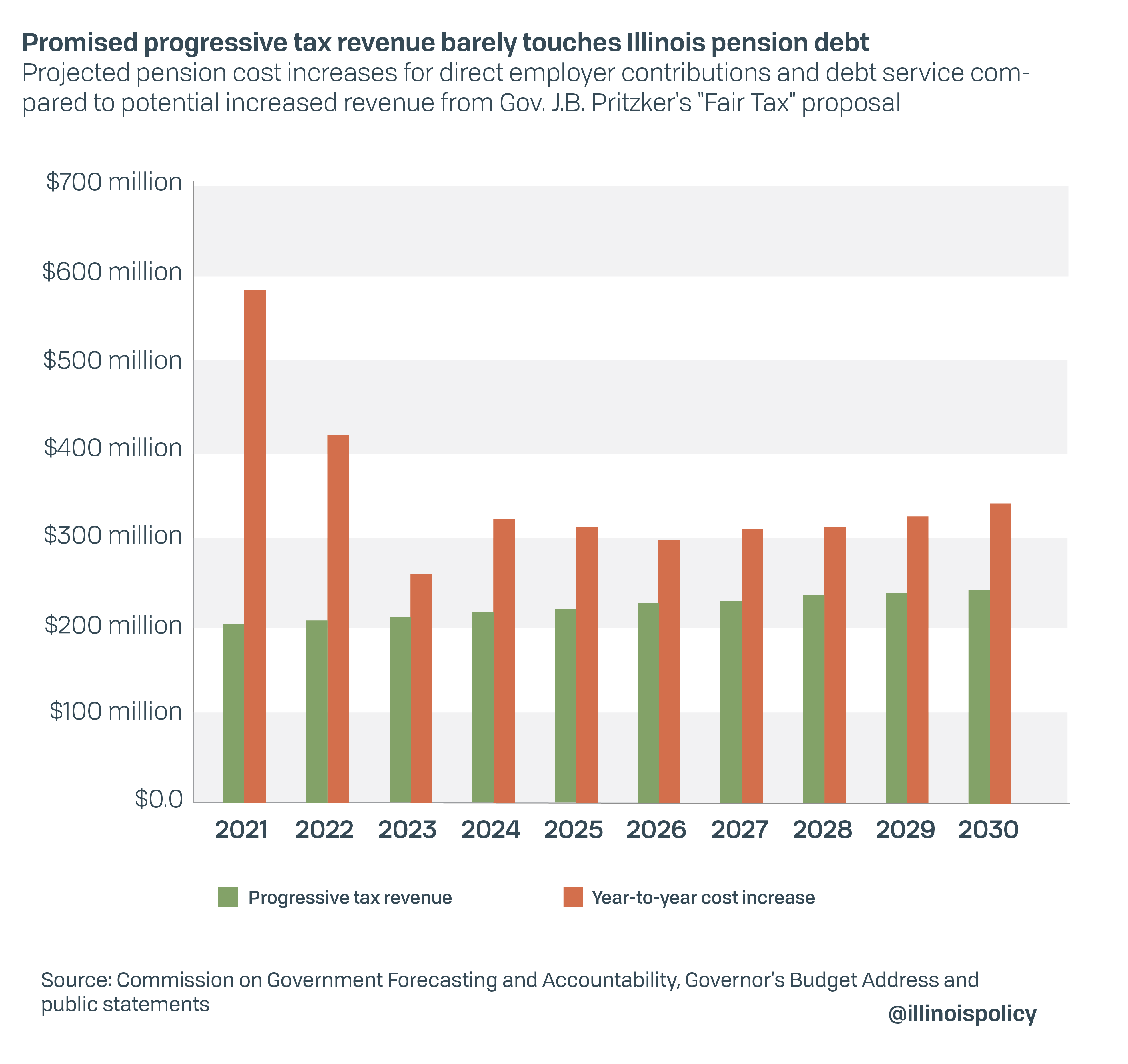

Specifically, Pritzker promised to earmark an additional $200 million for pensions from his progressive income tax plan, a little more than 5% of the expected $3.7 billion taxpayers would send to Springfield if voters approve the progressive tax Nov. 3.

This isn’t enough to even keep up with annual increases in the cost of pensions, which will be $577 million the first year the progressive tax could take effect.

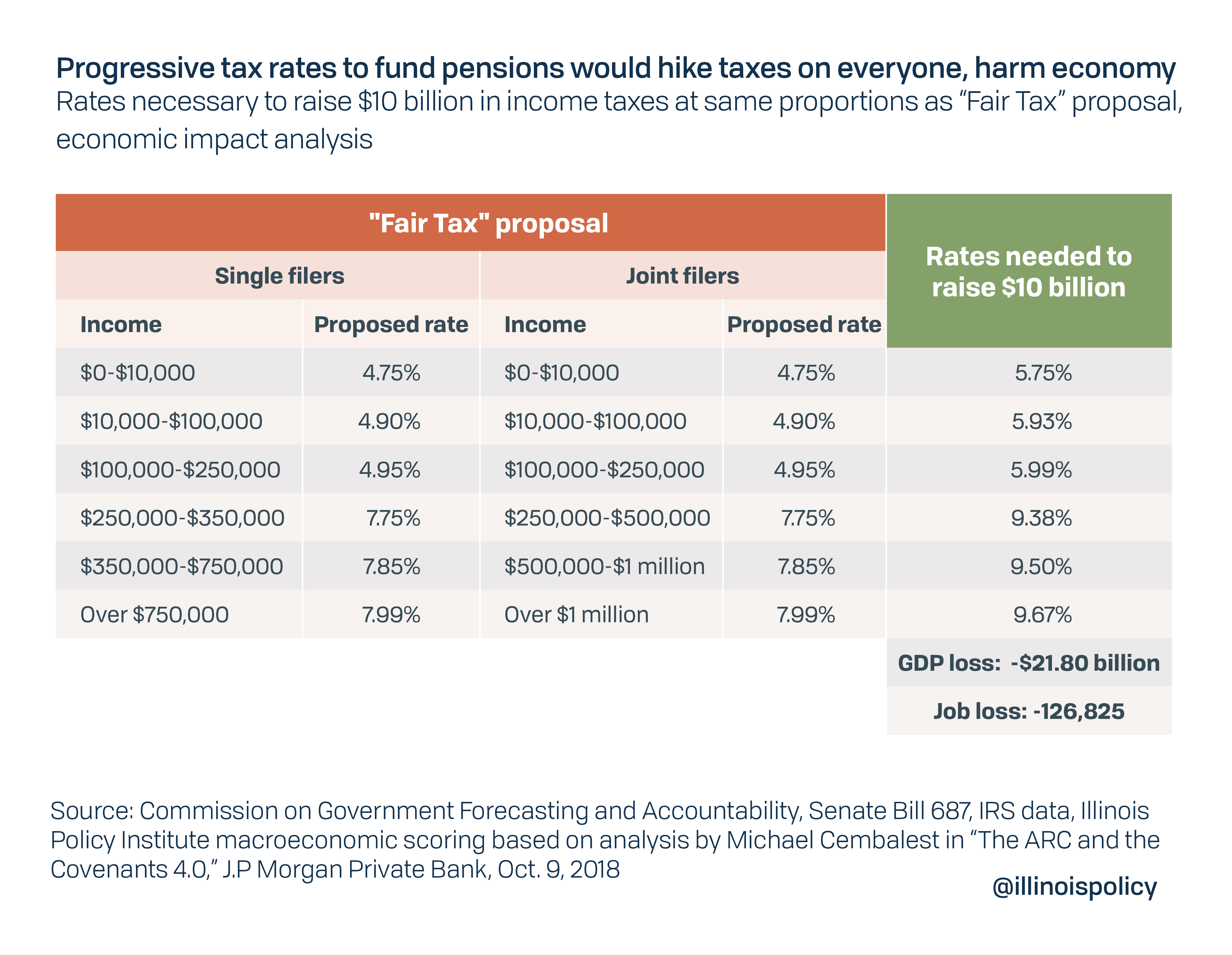

A progressive tax that would actually solve the pension crisis would have to raise taxes on everyone, including by about 20% on the poor and middle class.

The Illinois Policy Institute’s economic impact analysis is based on the research of a leading financial expert at J.P. Morgan who found Illinois would need to raise revenue equivalent to a 50% increase in the income tax to pay down retirement benefits at current levels. A progressive tax hike large enough to solve the problem could cost Illinois’ economy nearly 127,000 jobs and $21.8 billion in lost gross domestic product.

Simply put, tax hikes are not a viable solution to the pension crisis.

5. Extend partial, optional pension buyouts

The fiscal year 2019 budget created an optional pension buyout program for members of the pension system who are either recently retired or “inactives” – those who quit working for the state before retirement age but had already vested.

The Illinois Policy Institute warned that savings from these buyouts were “speculative and unlikely to materialize” when they were originally offered to employees until 2021. In the first year, the buyouts saved $13 million, just 3% of the projected $400 million savings.

Pritzker extended the program through 2024 in his first budget and has publicly claimed they can now save $25 billion, a statement rated “false” by PolitiFact. Pritzker’s administration admitted in audited statements to potential investors that it can’t promise any specific savings from the buyouts.

Constitutional pension reform is the only comprehensive solution left

The only sustainable way out of Illinois’ pension crisis – and its negative effects on taxpayers, residents in need, the economy and government finances – is to reduce pension liabilities with benefit reforms. As shown below, benefit reforms can solve the pension problem while protecting both taxpayers and government workers. The biggest obstacle to a brighter future for Illinois has been and remains the lack of political will to pursue meaningful reform.

The Illinois Policy Institute’s pension reform plan follows the bipartisan 2013 reforms as an example. Specific changes to benefits and plan structure would be as follows:

- Increase the funding target to 100% from 90% in accordance with actuarial best practices. The goal year for 100% funding would remain 2045.

- Gradually increase retirement ages for current workers under age 45 by a maximum of five years.

- Apply a pensionable salary cap of $100,000 that grows with inflation. Government workers could still earn more than $100,000, but their pensions could not be based on more than the cap. The cap would only apply to employees not currently receiving a retirement check.

- Replace Tier 1 retirees’ 3% compounding benefit increase with true cost-of-living adjustments tied to inflation. Annual increases would be simple, not compounding, and rise with the urban consumer price index as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Increase Tier 2 COLAs from half of inflation to full inflation. This would end the unfair subsidization of older workers by younger workers and could prevent a potential lawsuit.

- Implement COLA holidays to allow inflation to catch up to past benefit increases. If a worker has been retired for eight years or more, they would skip every other year for 16 years for a total of eight adjustment periods at 0%. If a retiree has been receiving benefits for seven years, they would skip one payment every other year for 14 years, and so on.

- Enroll all newly hired employees in a defined contribution personal retirement account with a 4% guaranteed employer match. This would ensure the state never gets into pension trouble again, as defined contribution systems are inherently less risky and more predictable. This would also provide state workers with a portable retirement benefit they could take with them from employer to employer, rather than being forced to stay with the state in order to maximize retirement benefits.

An original actuarial analysis commissioned by the Illinois Policy Institute shows how far these modest reforms can go to bring Illinois back from the brink. The analysis was performed by Elizabeth Bauer, a credentialed actuary who writes about pension policy for “Forbes” magazine. Bauer’s analysis showed that in the first year, this reform package would save nearly $2.4 billion for the state budget. From now until 2045, these reforms would save the state more than $50 billion in taxpayer contributions.

These savings are also achievable while preserving the core benefit for every worker and retiree. No retired person would see the size of their current check decrease and no current worker would see their currently promised monthly annuity shrink.

There is no fairer solution for both taxpayers and those relying on Illinois’ pension systems for their retirement security.