Illinois property tax relief begins by culling nearly 7,000 local government units

Illinois’ overabundance of local government layers provides ample room to consolidate and save property taxes.

Illinois’ property tax task force will share its recommendations to reduce Illinois’ sky-high property taxes in less than a month. Cutting Illinois’ nation-leading number of government units should be in its crosshairs.

Consider: If Illinois did away with townships, a homeowner paying $6,000 in property taxes could save as much as $210 on his or her property tax bill.

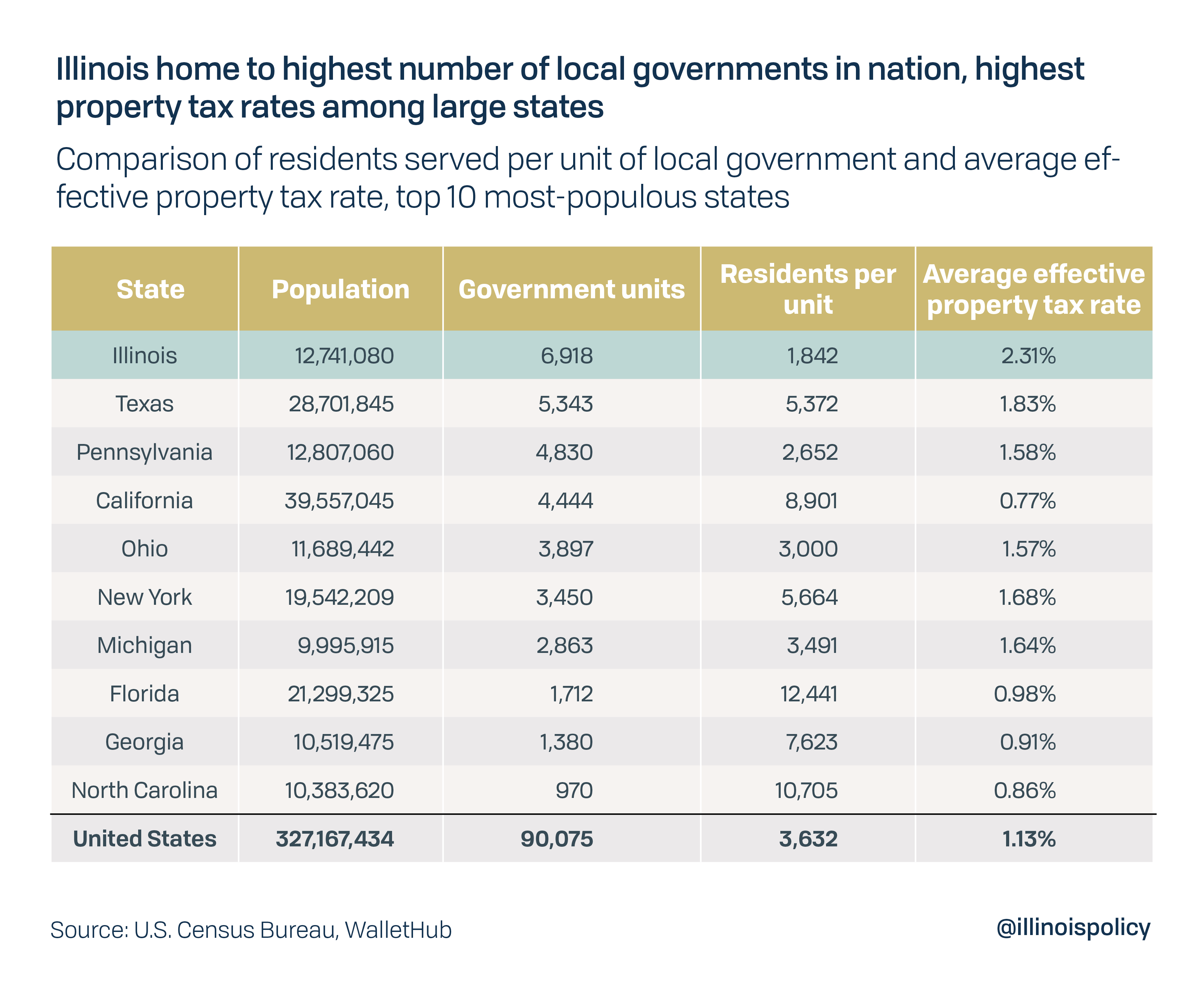

Illinois is home to nearly 7,000 units of local government, more than any other state in the nation and twice as much government per person as the nation’s average. Townships are one example of government units that have largely outlived their purpose. Illinois has more than 1,400 townships, which cost taxpayers outside of Cook County $574 million – or 3.5% of all downstate property tax collections – per year to deliver simple public services that cities or counties could just as easily deliver.

Illinoisans pay for each of layer of local government – cities, school districts, park districts, mosquito abatement districts and others – through their property taxes. With such a large number of government bodies to fund, it’s no wonder the average Illinois homeowner pays the highest effective property tax rate among large states and second-highest property taxes in the nation.

Many local government units in Illinois wastefully perform overlapping functions, and others provide services that could be more efficiently delivered by a larger government unit. Texas, a state with more than twice as many residents and five times the amount of land as Illinois, has almost 2,000 fewer layers of local bureaucracy than the Prairie State.

Long-term property tax relief can only come through constitutional public pension reform that ties future, unearned increases to the actual rate of inflation. Until that happens, state leaders could give taxpayers the tools to control how much local government they’re willing to pay for.

Consolidation is already happening and is cutting back on waste. For example, the city of Evanston and the now defunct Evanston Township shared the exact same borders. In 2014, voters agreed to dissolve the township, and the city assumed the township’s responsibilities that year. Evanston saved nearly $800,000 in the first year following the dissolution, in addition to seeing improvement in services.

In the spirit of other recent consolidation reforms, state lawmakers should make it easier for local taxpayers to trim layers of local government at the ballot box.