Lightfoot must pursue pension reform, reasonable labor contracts to fix Chicago’s budget

Persistent budget deficits, enormous and growing pension obligations, a high debt burden and labor contract negotiations all await Lori Lightfoot as she settles into office.

New Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot gets no honeymoon. Instead, she inherits daunting fiscal challenges without easy solutions.

Chicago’s structural budget deficit dates back to at least 2005. Outgoing Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration announced the fiscal year 2020 gap could be as high as $700 million, driven mostly by higher pension payments caused by poor investment performance in 2018 among the city’s pension funds.

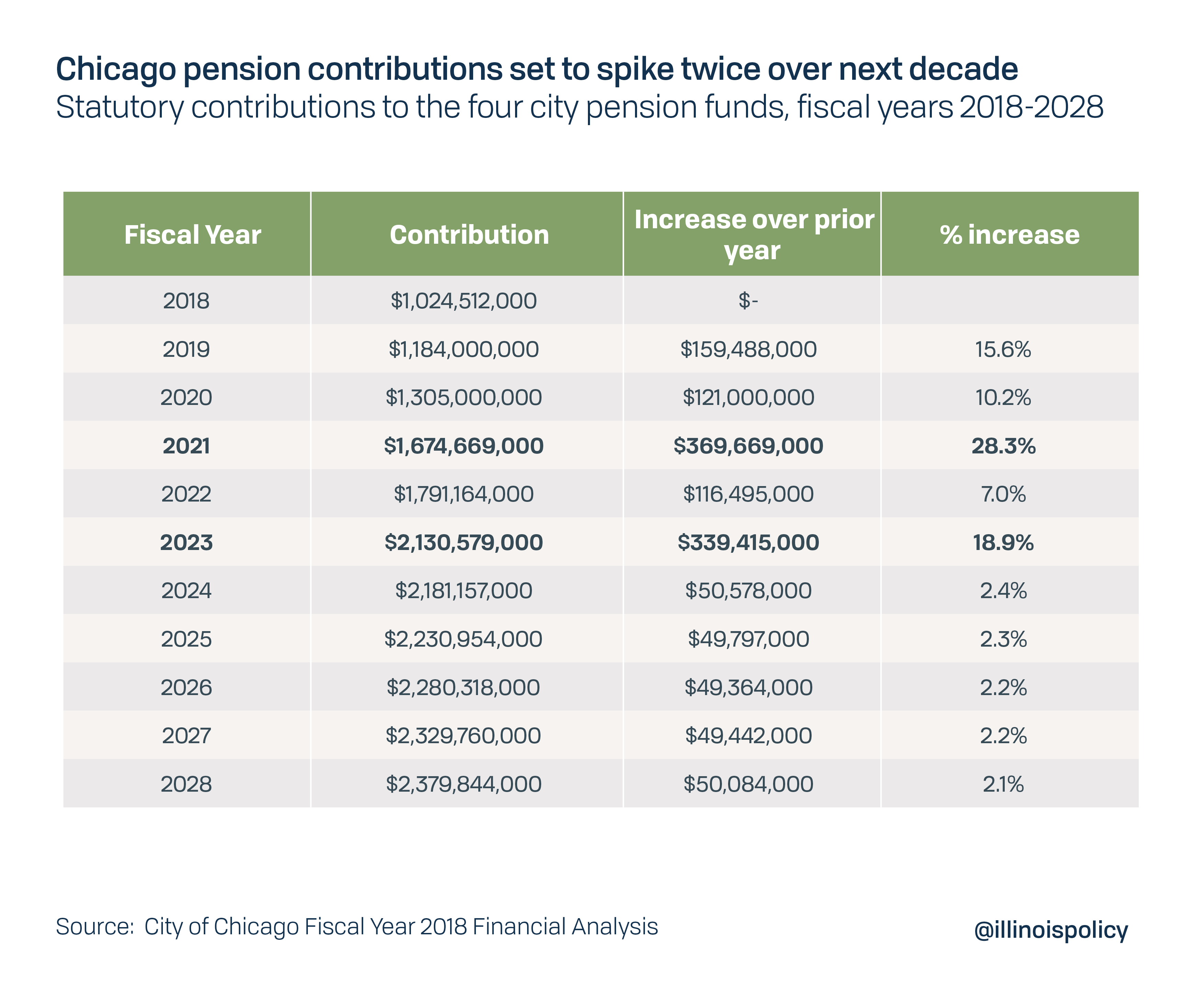

The pension pressure will continue during Lightfoot’s tenure: The city’s pension funds require rapidly increasing contributions during the next four years.

Also, Chicago’s bond debt totaled $9.6 billion at the end of fiscal year 2017, a 57% increase in 10 years. Moody’s Investors Service assigned a junk bond rating of Ba1 to that debt in July 2018.

Lightfoot should lead by putting the city on the path to fiscal stability – without resorting to tax hikes on a city with a shrinking population that has seen $864 million in tax hikes during Emanuel’s administration. Unfortunately, she already is telling taxpayers to expect more pain.

Instead, Lightfoot should call for the Illinois General Assembly to take up pension reform and should negotiate reasonable contracts that hold down the city’s labor costs. With pension reform and restraint in spending and taxing, the city could rebuild its finances, conserve money for basic services and keep more residents from leaving the city.

Chicago’s structural budget deficit must be solved

Lightfoot is starting the budget process for 2020, which will be tough given the city’s chronic structural deficit and skyrocketing pension costs.

Chicago’s structural budget deficit – caused by the city habitually spending more than it collects in revenues – reached a high of $655 million in 2011 and gradually came down to a projected $98 million for fiscal year 2019. That was just the city’s day-to-day operating deficit for basic services. The gap was projected to increase to $252 million in 2020, but that did not include an additional $276 million contribution to police and fire pension funds. As the Emanuel administration prepared to exit City Hall, they increased their estimate of the 2020 budget deficit to as much as $700 million because the pension funds suffered losses in 2018 rather than achieving the 7-percent investment target.

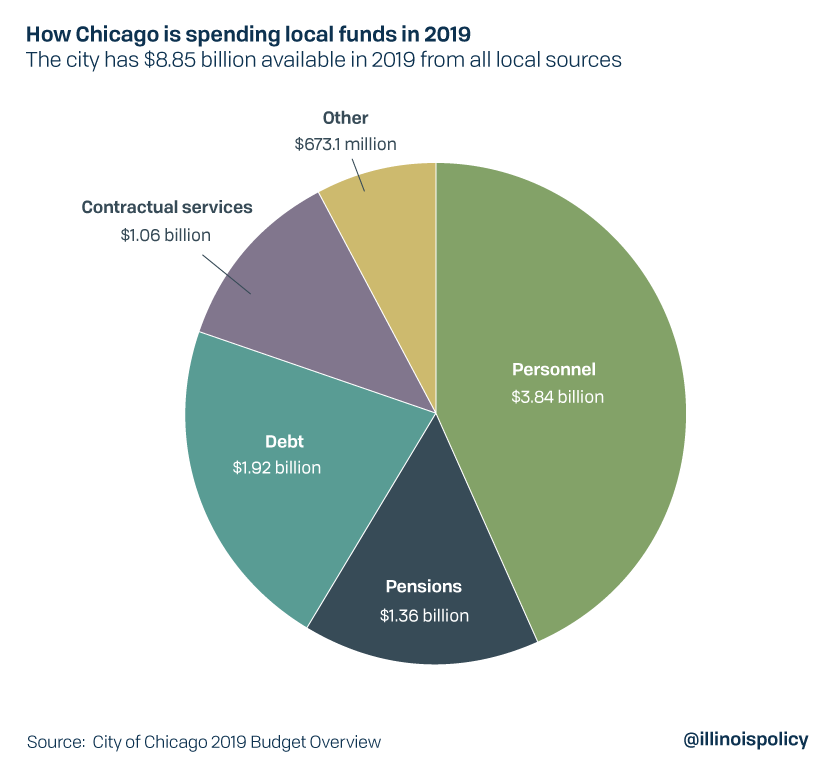

To cover the budget deficits in the past, the city has resorted to selling assets and using reserve funds. According to the 2019 Budget Overview, the last one prepared by the Emanuel administration, Chicago will have $8.9 billion – revenues from taxes, fees and fines, but excluding grant money – to spend this year.

These revenues will go to pay the city’s expenses. While personnel-related costs are the highest, a combined 37% of the city’s budget, including all of the city’s property tax revenues, will go to pensions and principal and interest payments on Chicago’s debt.

The 2019 Budget Overview presents a balanced budget by making assumptions that savings can be achieved in different ways, such as on equipment cost reductions, government reform and better fiscal management. However, experience shows the city consistently spends more than it receives regardless of what the budget states.

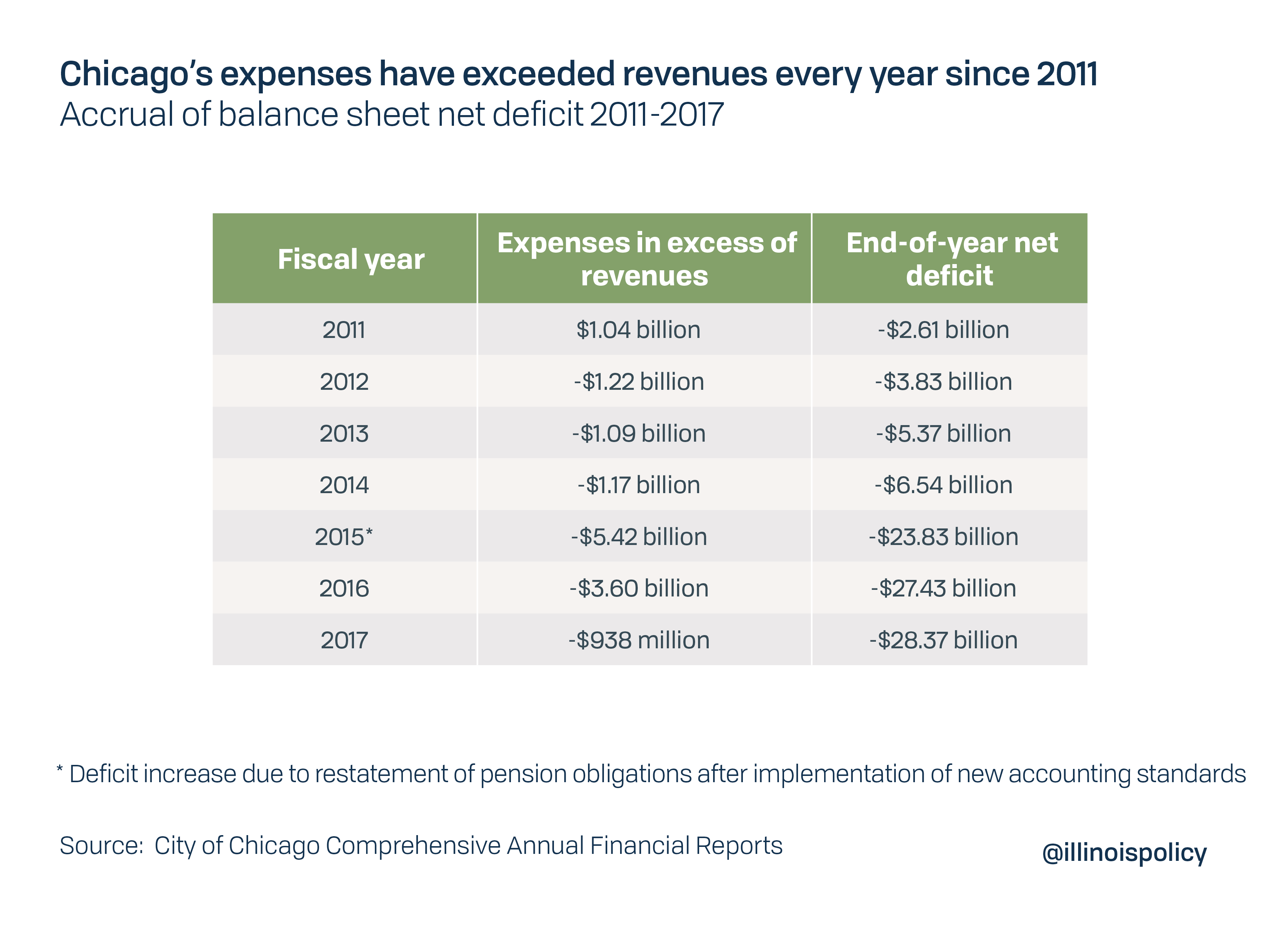

According to Chicago’s Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, or CAFR, for 2017, the most recent available, the city spent over $900 million more than its revenues in 2017. Since 2011, the city’s net deficit – the amount by which the city’s short- and long-term liabilities exceed its assets – has increased to over $28 billion.

In 2011, the net deficit was only $2.6 billion. Despite claims that the city has made progress by reducing the structural budget deficit since 2011, Chicago’s financial condition has deteriorated dramatically since then because the city spends more than it receives, and its long-term liabilities have grown because of higher pension obligations and debt.

Chicago taxpayers bear a high debt burden

Chicago taxpayers bear the highest total debt burden among the country’s 10 largest cities, an astounding $119,000 per taxpayer, according to Truth in Accounting. The group counts the city’s pension and other direct debt, such as general obligation bonds, as well as debt for other governmental units for which Chicago taxpayers are responsible, such as Cook County and the state of Illinois.

Of the governmental agencies in Chicago that are funded by taxpayer dollars, the largest is Chicago Public Schools, or CPS. For its fiscal year ended June 30, 2018, CPS brought in a little over $6.5 billion in revenue and spent just under $6.5 billion. CPS also took $2.9 billion in property taxes, more than twice what Chicago receives from its property tax levy.

CPS has pension and debt challenges as well. Over 21 percent of what was spent in fiscal 2018 went to pension and retirement benefits ($763 million) and debt service ($651 million). The Chicago Teachers Pension Fund was only 48% funded and had almost $12 billion in debt as of June 30, 2018.

A long-term plan for fiscal stability requires pension reform

Chicago’s budget problems can’t be solved without addressing the city’s pension crisis. The four pension funds the city controls have over $27 billion in debt and are only 26 percent funded. Lightfoot has suggested those figures may be even worse. Those funds are the Municipal Employees’ Annuity and Benefit Fund, the Laborers’ Annuity and Benefit Fund, the Policemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund and the Firemen’s Annuity and Benefit Fund. Required contributions to those pension funds are set to increase dramatically. This threatens to overwhelm the city’s budget and crowd out spending on critical city programs – without stopping the growth in total pension debt.

In the first year of the Lightfoot administration, the required pension contribution to the four city-controlled pension funds will increase by $121 million over the fiscal year 2019 amount, to top $1.3 billion. The increase in contributions will accelerate rapidly and reach over $2.1 billion in 2023, a roughly $1 billion increase from just four years earlier.

According to Chicago’s 2017 CAFR, pension payments absorb most of Chicago’s property tax levy, with the balance going to debt service. Property taxes were already increased by $543 million during the Emanuel administration. Nearly all of the $321 million in water and sewer tax increases and 911 fees passed since 2015 will go directly or indirectly to pensions as well.

That is why it is essential that Illinois pass a constitutional amendment that protects earned pension benefits but allows changes in future benefit accruals. As Emanuel did before leaving office, Lightfoot should endorse an amendment to the restrictive pension clause in the Illinois Constitution so the growth in future pension obligations can be curtailed. Consolidating Chicago’s pension funds with downstate funds could also generate significant savings. Fund consolidation could take advantage of economies of scale, eliminate duplicative administrative costs and create greater investment opportunities, according to the Civic Federation.

Lightfoot must negotiate labor contracts that Chicagoans can afford

As she faces a steep budget deficit, increasing required pension contributions and a shrinking city population to pay for it all, Lightfoot will need to hold firm in her negotiations on new collective bargaining agreements with the city’s unions.

Between 2007 and 2017, the Fraternal Order of Police, the Coalition of Unionized Public Employees, the Chicago Firefighters Union and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees received salary increases between 21 and 26 percent. The city simply does not have money for increases like those again.

Chicago has 44 union contracts, all of which expired in 2017. Contracts with the 34 trade unions, which represent 22 percent of the city’s workforce, have been renegotiated through the Coalition of Unionized Public Employees. The new contracts granted 2.1 percent annual pay increases, in line with economic realities, but did not do away with costly work rules and prevailing wage requirements.

As Lightfoot negotiates with police and firefighters, which represent 38.5 percent and 14.6 percent, respectively, of the city’s workforce and a majority of its personnel expenses, she should heed the advice of the Office of Inspector General, or OIG. The OIG identified characteristics of the contracts that should be reconsidered because they affect the city’s capacity to innovate and modernize its operations to deliver services more efficiently and transparently. These include:

- “Side letters,” amendments outside of the contracts that create ambiguity and undermine transparency. Some of these remain in effect after a contract has expired and can prevent efficient contract enforcement and administration. According to the OIG, there are 42 police and 51 firefighter side letters in their contracts.

- A lack of adequate “reopener provisions” that would allow the city to reopen contract negotiations in the event of a deterioration of the city’s finances during an economic downturn.

- “Duty availability pay” for which no specific purpose is stated in contracts but is understood to compensate police and fire personnel because they may be called to duty on their days off. Chicago paid over $56 million in duty availability pay in 2016.

- “Compensatory time buybacks” that permit police personnel to accumulate up to 200 hours of compensatory time annually in lieu of overtime during their careers and cash it in upon retirement. Chicago paid out almost $19 million in compensatory time buybacks between 2013 and 2017.

- “Holiday on furlough days,” also known as “Daley Days,” that consider fire personnel to have worked on a holiday if the holiday occurs during a vacation.

- Employees should bear more of their health care costs. Currently, health insurance premiums paid by city employees are capped at $2,228 annually regardless of salary. By contrast, the national average for employees at private sector firms with more than 200 employees is $4,917.

The fiscal path for Lightfoot is difficult but achievable

There are no easy or quick solutions to Chicago’s fiscal problems. It will take many years for the city to dig out from its pension and other debt obligations. But Mayor Lightfoot must show the leadership and courage necessary to take steps needed now to put the city on the path to fiscal stability.

The first step must be advocating for a state constitutional amendment to reform Chicago’s pension systems to protect earned benefits while slowing the growth in new pension obligations.

However, even if an amendment to the pension clause is passed by the General Assembly, it must be approved by Illinois voters in a general election. The earliest this could happen is 2020. Lightfoot need not wait for a full constitutional amendment to be passed to achieve savings. While urging the state legislature to pass the amendment, she could propose pension contributions based on new post-reform benefit formulas. If the amendment fails, required contributions would revert to those under the current formula.

As personnel-related expenses consume the largest portion of the city’s budget, it is imperative that Lightfoot insist in upcoming labor negotiations on pay raises that are in line with economic reality and affordable for Chicago taxpayers. She should also consider other ways to make city government more cost effective, such as requiring employees to pay a greater share of their health care costs and eliminating or limiting expensive provisions such as compensatory time buy-backs.

The full results of some of Lightfoot’s efforts may not be felt until after she leaves office, but she must resist the easy out of hike taxes and avoid focusing on short-term results. She needs to make tough choices and take the long view of the city’s fiscal situation, or Chicago faces a dim future.