Without pension reform, progressive income tax amendment guarantees tax hikes on Illinois’ middle class

The current progressive income tax proposal would fail to pay down the state's unfunded liability while damaging Illinois' economy.

On May 20, Democrats in the Illinois House Revenue & Finance Committee approved Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s prized progressive tax constitutional amendment. While the Senate had previously passed a new income tax structure – already different from the governor’s original proposal – the House Committee also passed the amendment without putting in income tax rates.

Pritzker and other proponents of replacing Illinois’ flat income tax with a progressive tax have claimed the switch would allow the state to fund its skyrocketing pension obligations, pay off its bill backlog, spend more on education and social services, enable property tax relief and more.

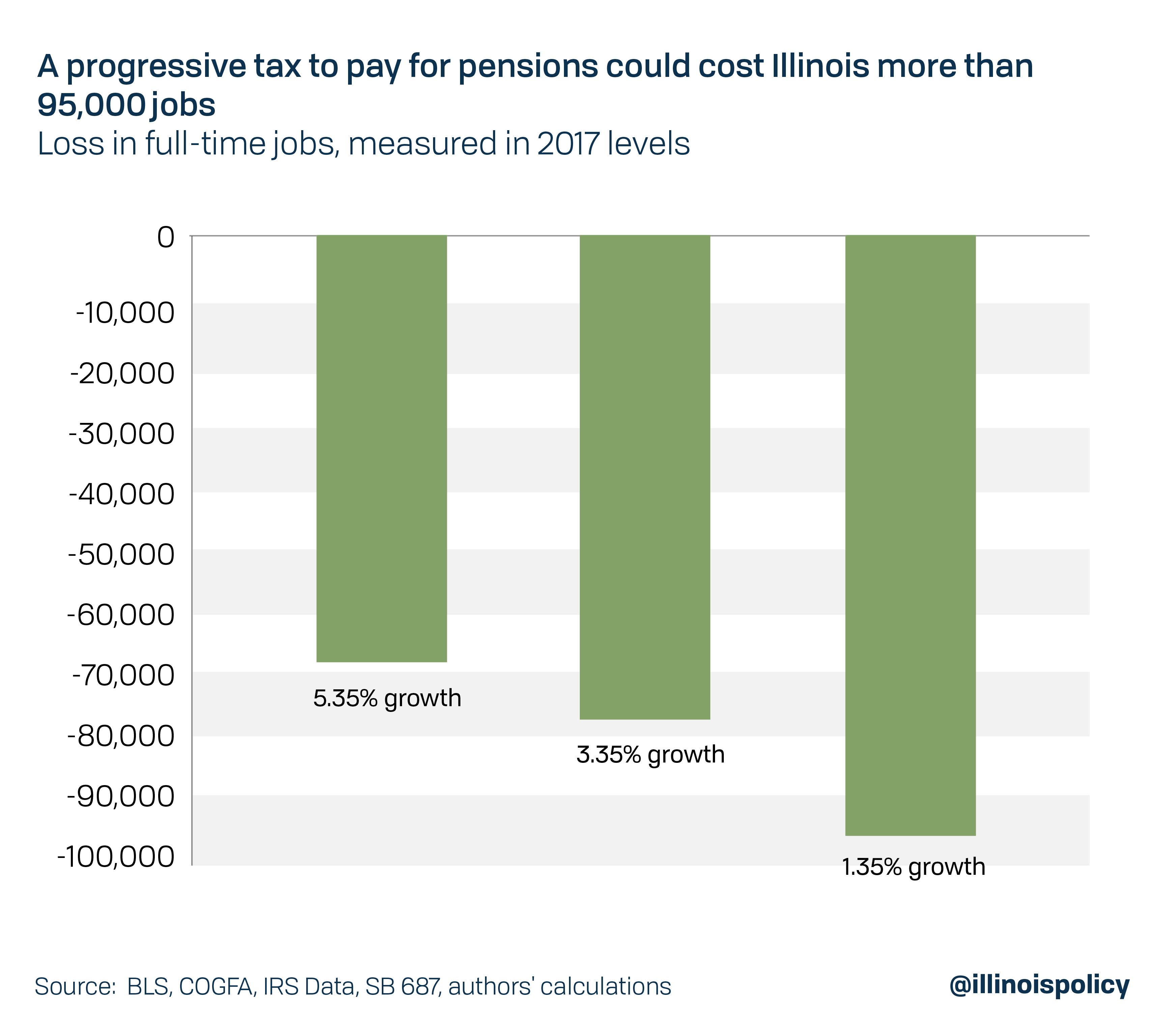

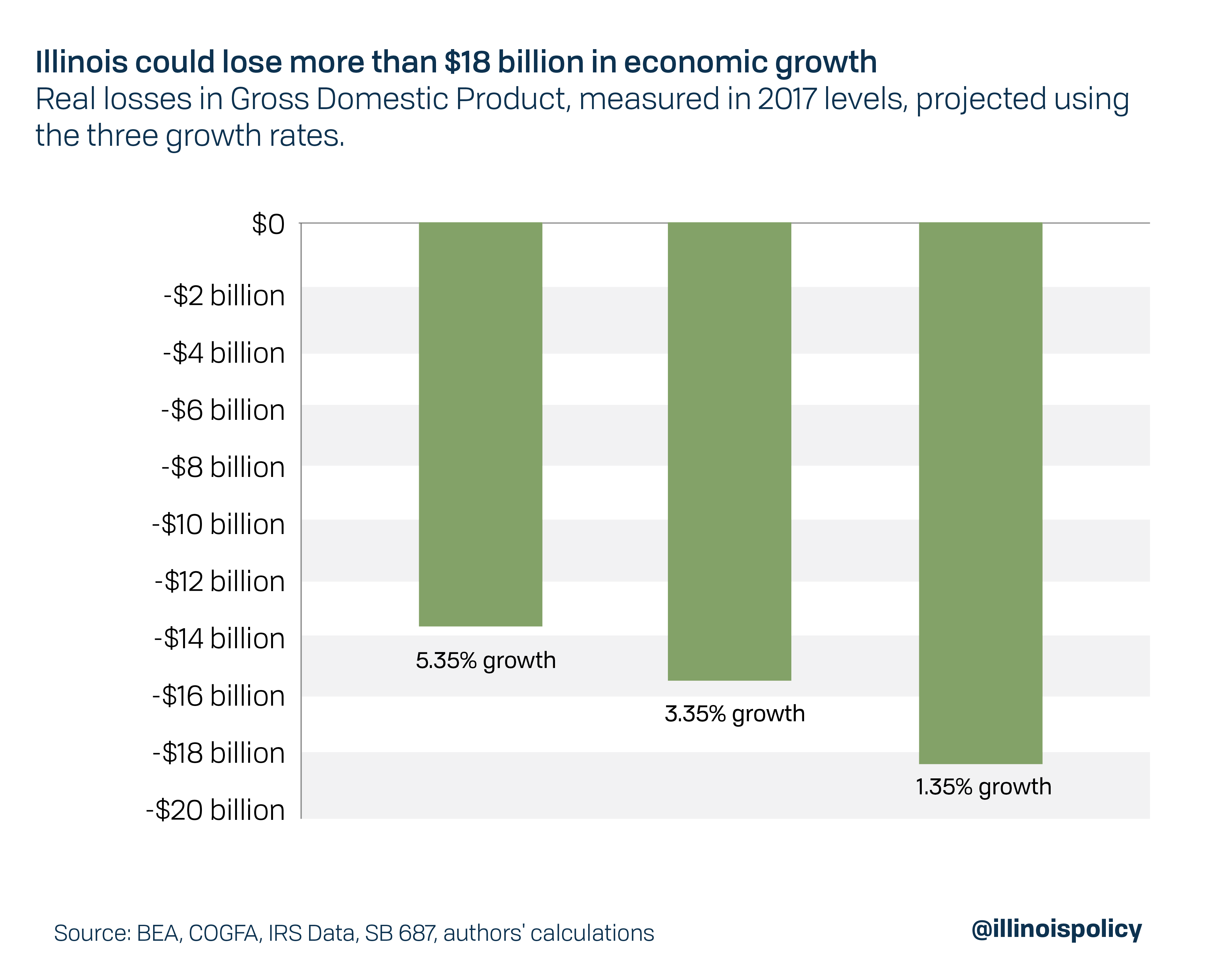

But progressive tax proponents need to face that without pension reform, Illinois’ crushing public employee retirement debt will consume every new dollar generated with a progressive tax – and will require further tax hikes to fully pay off pension debt, as Pritzker has advocated. Illinois could lose up to 95,000 jobs and the economy could suffer up to $18 billion in economic impact were it to try to use a progressive tax to pay off the state’s unfunded pension liability within 40 years, a new Illinois Policy Institute study shows.

Current progressive tax proposals

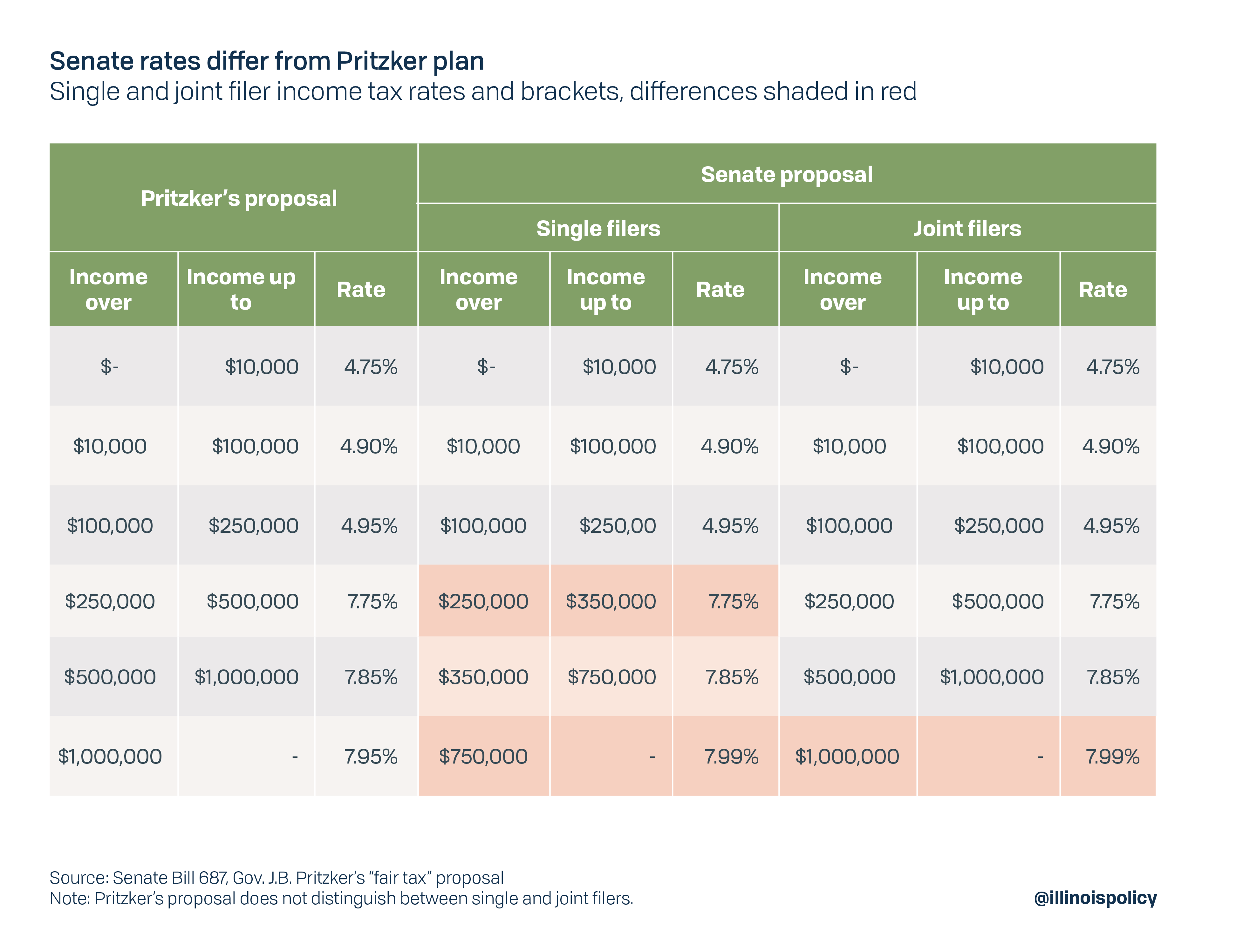

While Pritzker has been campaigning for months on his own proposal, the rates and brackets passed out of the Senate are different from the governor’s. Pritzker’s proposal levied a 7.95% flat rate on the highest income bracket while the plan passed out of the Senate features a 7.99% flat rate on the highest income bracket. That top bracket also now kicks in at a lower level for single filers: $750,000 instead of $1 million.

The state’s corporate income tax rate would also be bumped up to 7.99% from 7%. Pritzker’s plan hiked the corporate income tax to 7.95%.

Of all the things Pritzker and other proponents have promised the progressive income tax would do, the most significant is addressing the state’s pension crisis. Currently, Illinois’ five state-run pension systems officially report $137 billion in unfunded liabilities, though Moody’s Investors Service has estimated the number stands at $232 billion. Despite the state spending more on pensions each year, these unfunded liabilities continue to grow.

Although many independent groups as well as mayors and municipal leaders have called for reforms to Illinois’ unsustainable pension system, Pritzker has thus far rejected those ideas. Instead, he’s called for a graduated income tax and other tax hikes to cover the rising debt.

While Illinois taxpayers might expect the graduated income tax to pay for public services such as education, the reality is the state’s sky-high pension debt ensures any future revenue increase mostly will go to pensions.

Credit ratings agencies have noted the promise of a progressive income tax that pays for pensions, but have also pointed out that “[a] positive outcome for the state’s credit standing would require that the new system yield substantial net new revenue, without material damage to the economy, and that the new revenue be largely allocated to addressing the state’s retirement benefit liabilities on a recurring basis. A negative outcome – characterized by growing economic challenges and scant progress addressing pension funding needs – is also possible.

Thus, according to credit rating agencies, a progressive income tax would only improve Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation credit rating if it resulted in a huge influx of revenue that goes almost exclusively to pensions. It must do so without harming the state’s economy. This would be a nearly impossible feat.

Can the Senate’s plan pay for pensions?

The Illinois Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability estimated the state’s unfunded liability at $136.8 billion at the end of fiscal year 2019. Similar to Haasl, Mattoon and Walstrum’s (2018) study presented at a pensions forum at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the Illinois Policy Institute’s analysis assumes that all additional progressive tax revenue – revenue above what the current flat income tax would have brought in – would go directly to pay for pension debt.

This exercise assumes the state will be able to accurately predict the normal cost of servicing state pensions. They have historically failed to do so, leading to further growth in unfunded liabilities.

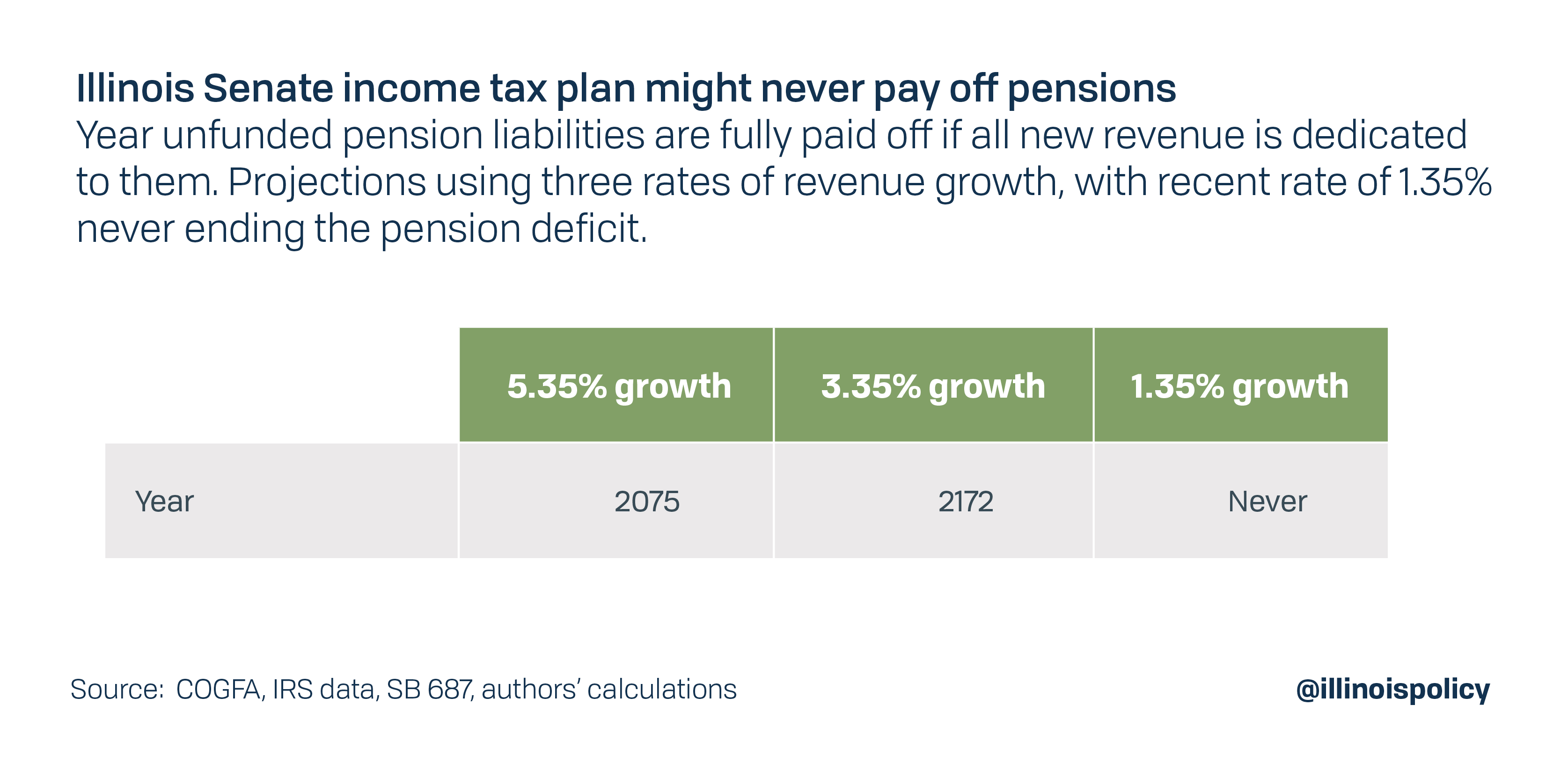

If annual income tax revenue growth caused by secular income growth matches the state’s recent experience, the progressive income tax rates passed by the Senate will fail to pay off the state’s pension debt – ever.

In order for the Senate’s current plan to fully pay for pensions, the annual increase in tax revenue caused by increases in the tax base would have to remain at 5.35% annual growth – nearly 400% higher than the most recent 5-year compound annual growth rate of 1.35%. For the Senate plan to work, the tax base would need to grow at the 5.35% rate for a 54-year period (see appendix).

In a scenario where secular income growth causes income tax revenues to grow at 3.35% annually – 250% faster than the recent 1.35% rate – it would take the state 151 years to pay down the unfunded pension liability. Obviously, these benefits will have to be paid out before then, and avoiding further credit downgrades would require even more resources being diverted to pension debt..

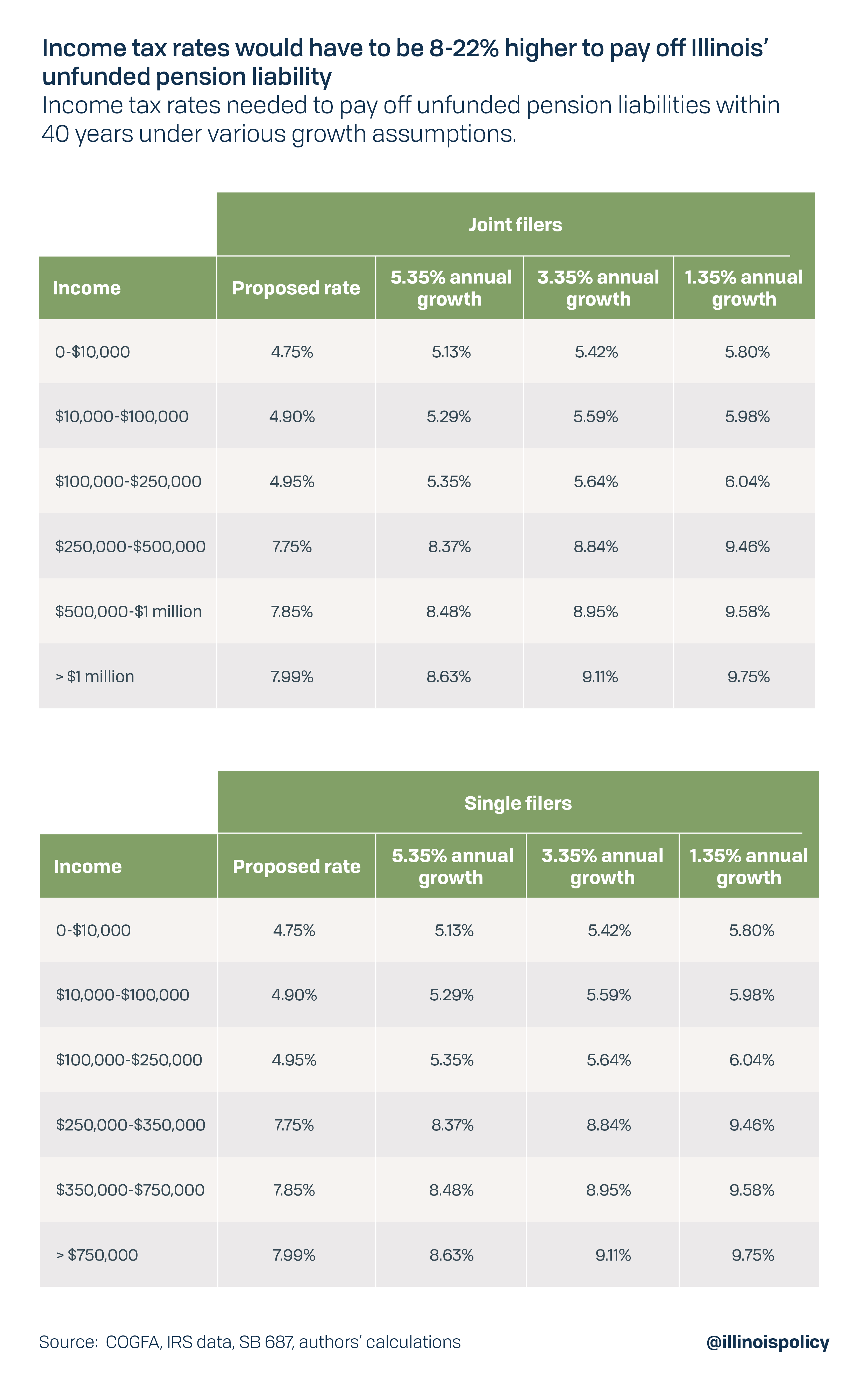

The Haasl, Mattoon and Walstrum study referenced above suggested the state could pay for these costs on a 40-year timeline with a statewide property tax – an even more unpopular proposal. Using the same 40-year timeline, and maintaining the same income brackets as the Senate’s proposal, income tax rates would have to be much higher to pay down the state’s unfunded pension liability (see appendix).

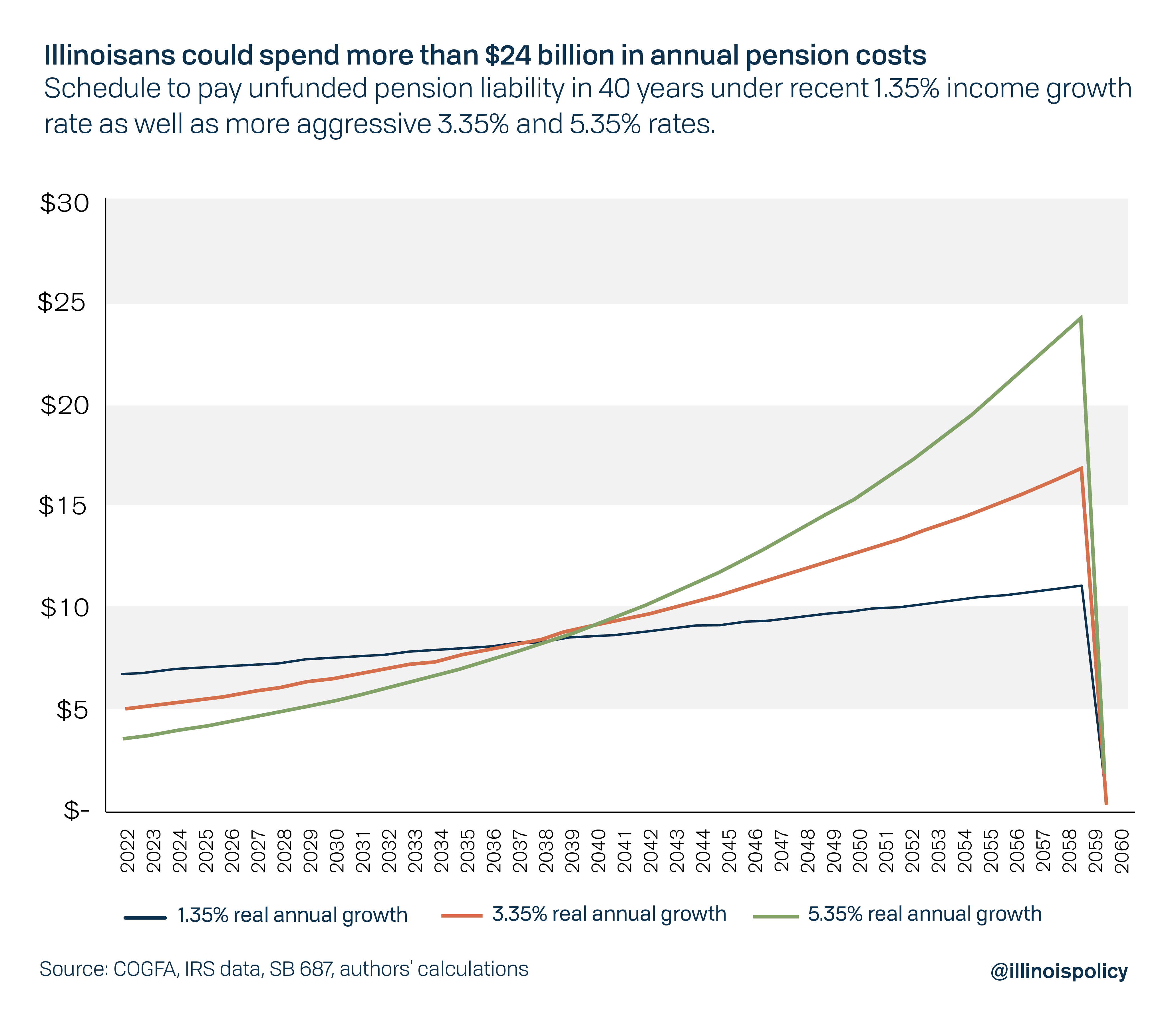

Even using the most generous assumption regarding natural growth in Illinois’ income tax revenue, income tax rates would have to be raised on everyone – from 8% to 22% higher than the rates in the Senate’s proposal – in order to pay down the unfunded pension liability within the next 40 years (see appendix). Again, this assumes every dime of additional revenue goes to pensions and would require much higher tax rates than currently proposed.

The lower the growth in revenues is, the higher income tax rates will have to be in order to pay down the pension debt. Therefore, under the lowest growth assumption, tax rates are the highest and bring in the most additional revenue in the first year, though the faster growth assumptions eventually generate more revenue.

Effects on the economy

Moody’s second, and perhaps most important requirement, for a progressive tax that pays for pensions while avoiding a credit downgrade is that the new tax doesn’t inflict material damage on the economy. Unfortunately, the tax increase necessary to eliminate the state’s pension debt would crush Illinois’ already weak economy.

When the Chicago Fed economists suggested a statewide property tax in May of 2018 to pay down pension debt, they claimed it would be the most fair, efficient and transparent option.

While property taxes may be one of the most “efficient” forms of taxation, this proposal illustrated the wide gap between Main Street and academia. At the time of the proposal, home prices in Illinois had yet to recover from their pre-recession peak and Illinois homes stayed on the market twice as long as the national average and came with some of the highest effective property tax rates in the nation – particularly in minority communities.

Yet as painful as a statewide property tax would be, a progressive income tax would be even more devastating to the economy.

Income tax increases have a negative effect on investment in human and physical capital (research and development, purchases of new machinery, or other equipment) that would otherwise improve labor productivity. This results in less income generation and lower living standards for everyone, and demonstrates why marginal tax rates should not increase with earning ability. (Diamond and Mirrlees, 1971; Gruber and Saez, 2002).

Following a long tradition in the economics literature, the Illinois Policy Institute estimated the potential effects of a progressive tax to pay for pensions through the lens of the neoclassical growth model – the most widely taught model of capital accumulation and long-run growth (see appendix).

The Institute’s research shows a progressive income tax plan with new revenue solely dedicated to paying down the unfunded pension liability could cost the state up to 95,000 full-time jobs. Even under the best-case scenario, the tax would still cost 56,000 full-time jobs.

The same goes for other effects of the tax hike on the economy. The tax hike could cost the state $14 billion-$18 billion worth of economic activity, with the lowest cost estimate derived from the smallest tax increase under the most generous growth assumption.

A better path forward

The large income tax collection necessary to pay for Illinois’ state pension debt would not satisfy Moody’s criteria of avoiding harm to the state’s economy. It would be even more economically disastrous than a statewide property tax.

The current proposal by the Illinois Senate would not produce enough revenue to pay off the state’s unfunded liabilities, even if all additional revenue were dedicated to pension debt.

Furthermore, while a significant income tax hike on everyone could potentially pay down the current pension debt within a reasonable time horizon, it would require higher tax rates than the current proposals, at a huge cost to the state’s economic future. Plus, that would require assuming that the state’s estimations of the debts are accurate; third-party estimates put the unfunded liability at nearly double what the state reports. An income tax hike big enough to truly satisfy the debt would wreak havoc on the state’s already fragile economy, resulting in further deterioration of the state’s credit rating.

Instead of doubling down on tax hikes, Pritzker and state lawmakers should look at structurally reforming Illinois’ pension system through an amendment to the state constitution’s pension clause. The Illinois Policy Institute shows how necessary, commonsense reforms can be achieved in “Budget Solutions 2020: A 5-year plan to balance Illinois’ budget, pay off debt and cut taxes.”

An amendment that protects pensioners’ already-earned benefits and allows for slower growth in future benefit accruals would help the state address its debt while protecting public employees’ retirements. It would also protect taxpayers, and any hope for the state’s economy.