As city of Springfield sees taxes rise, its population falls

With pension debt straining city finances, local politicians have insisted on turning to its declining population for more tax revenue.

Springfield city officials headed into this fiscal year hopeful new tax hikes would help repair the city’s broken finances. But they’ll need to rely on fewer people to pay up.

Springfield lost nearly 900 residents from July 2016 to July 2017, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Since 2010, Springfield has lost more than 1,700 residents, fueling Sangamon County’s population loss of over 1,300 residents countywide during that timeframe. A loss of residents means a loss of taxpayers, putting city officials in a budgetary bind intensified by growing pension costs.

Unfortunately for remaining Springfield taxpayers, City Council’s answer for budgetary shortfalls has been repeated hike taxes. The city’s fiscal year 2019 budget relied on an increase in its telecommunications tax and an expansion of its hotel-motel tax, while still facing a $4 million deficit. The city had also considered a 4 percent tax on natural gas, but it was unanimously voted down. Some city officials have flirted with the idea of a dine-in tax, but it has yet to be taken up for a vote.

This nickel-and-diming is on top of residents’ sky-high property taxes. According to ATTOM Data Solutions, a property data company, Springfield residents in 2017 paid an average effective property tax rate of 2.3 percent – nearly double the national average.

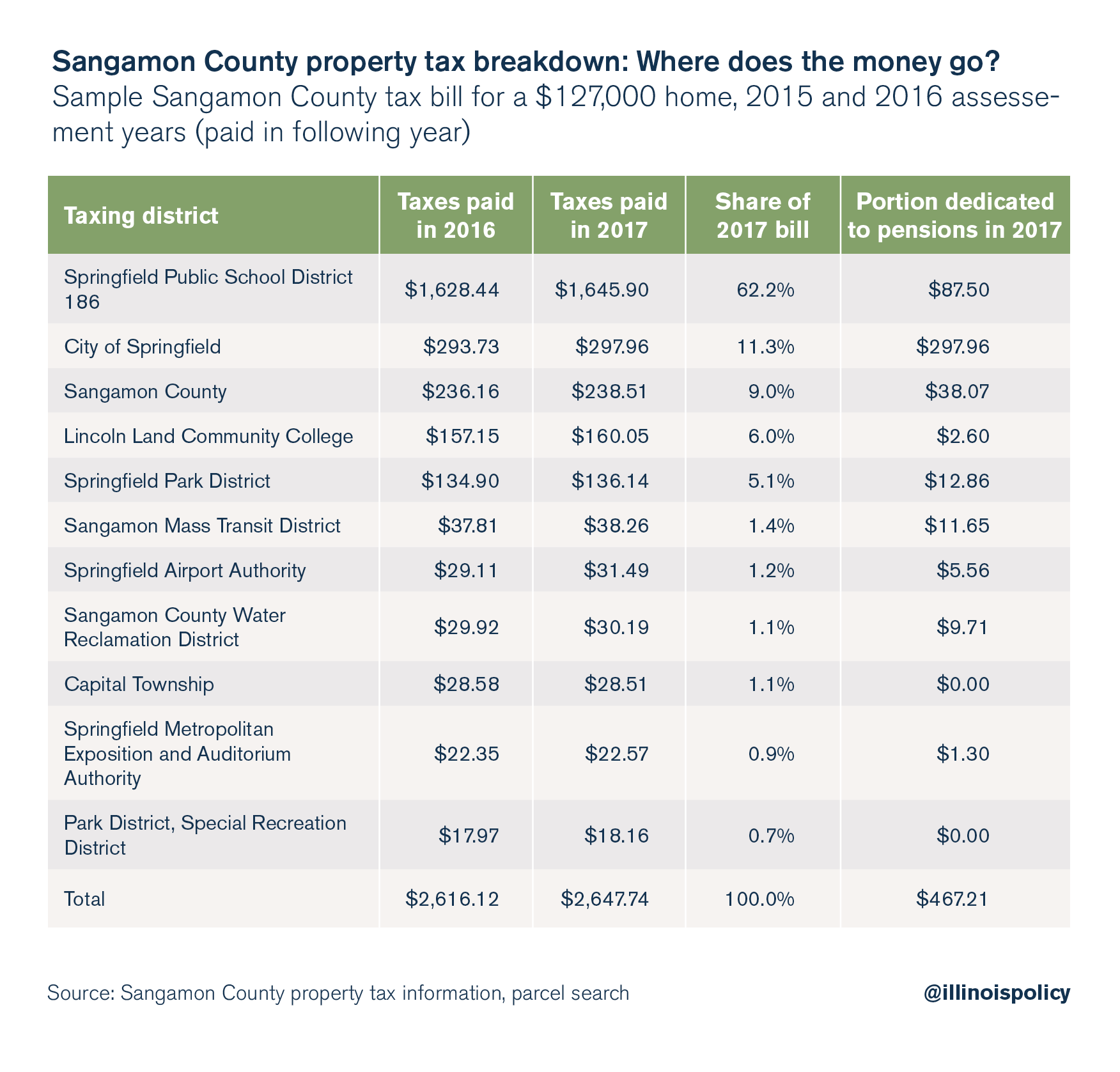

For the typical Springfield homeowner, those property tax dollars flow to 10 different units of local government. The property tax bill for a house in Springfield selling at about $127,000 – near the median home value – was more than $2,600 in 2017. More than 60 percent that property tax bill flowed to Springfield Public School District 186. In December, District 186 voted to raise its property tax levy by 3.3 percent for 2018, meaning residents’ property tax burden will only intensify. In 2017, nearly 18 percent of the typical Springfield homeowner’s property tax bill went to government workers’ pension funds, amounting to $467. And 100 percent of the amount paid to the city went toward government-worker pensions.

This growing property tax burden, and the continued insistence on new taxes, largely stems from the city’s troubled pension funds. In 2016, Moody’s Investor Service downgraded the city’s credit rating two notches, citing “considerable growth” in pension liabilities. In 2018, Moody’s again took note of Springfield’s pension woes, changing the city’s outlook from “stable” to “negative.”

In the face of a shrinking population, Springfield officials should turn away from tax hikes and instead look at spending reforms that bring the cost of government down to a level taxpayers can afford. Many of these reforms – including pension reform – will require action from state lawmakers.

Current residents aren’t likely to receive Springfield’s rising tax burden warmly, and local leaders should be wary of the fact that taxpayers always have the option to head for the exits.