Senate President John Cullerton says Illinois doesn’t need a revenue estimate

Agreeing on how much money one has to spend is a basic first step of budgeting.

Imagine a family sitting down to plan their budget around the kitchen table. Instead of starting with their expected income and prioritizing within that limit, they create a list of all the things they would like to buy: a new Ferrari, dining out daily at their favorite restaurant and whatever else they can think of. Any spending that they cannot immediately afford can just be placed on a high-interest credit card.

Sound ridiculous? Unsustainable?

That’s exactly how Senate President John Cullerton wants to plan the Illinois budget this year. In fact, that’s how Illinois lawmakers have been creating budgets since 2014. Poor budgeting processes go a long way toward explaining why lawmakers haven’t passed a balanced budget since 2001, despite a constitutional requirement to do so.

Gov. Bruce Rauner and Republican leaders in the House and Senate have put pressure on Cullerton and House Speaker Mike Madigan to certify a revenue estimate as a starting point for budget negotiations. Cullerton responded, “I wouldn’t get hung up on that … that gets into somewhat of a gotcha game and a political fight.”

That’s wrong.

Both statutory law and the Illinois Constitution appear to require the adoption of a revenue estimate. It is impossible for the balanced budget requirement to work without one. Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan issued an informal opinion in 2014 that stated, “[T]he General Assembly’s appropriation authority is limited by its estimate of funds available, which serves as ‘a ceiling of revenues within which they must appropriate and beyond which they may not go.’”

Adopting a revenue estimate is a necessary starting point for budget negotiations. Unfortunately, even when the General Assembly has adopted an estimate, the underlying numbers are often unreliable.

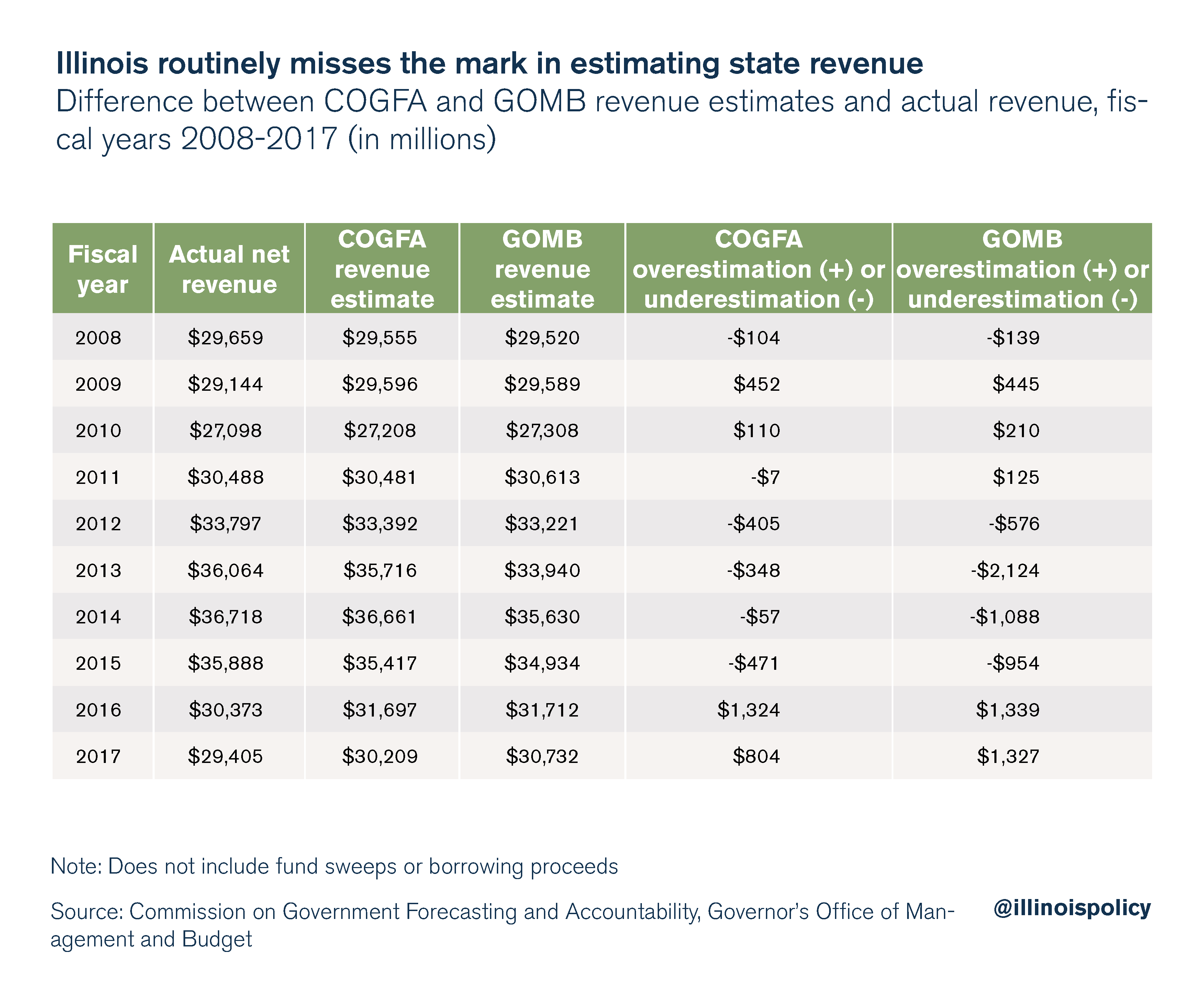

State law currently requires two separate entities to estimate revenue for the coming year. The executive estimate comes from the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, or GOMB, and is used by the governor in his annual budget proposal. A second estimate comes from the legislative Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, or COGFA. The General Assembly is then supposed to use these numbers to adopt its own official estimate for the budget process. Unfortunately, these two estimates rarely match either each other or the amount of revenue that actually ends up coming in.

Based on the standard for revenue projections used by the National Association of State Budget Officers – estimates within 0.5 percent of actual revenues are considered “on target” – COGFA revenue estimates have been accurate in only four of the last 10 years. GOMB estimates have been on target in only two of the last 10 years.

Even this standard is generous. “On target” in fiscal year 2010 meant an overestimation of $110 million dollars by COGFA, which is the size of the annual budgets of several entire executive agencies and boards. “On target” for fiscal year 2018 would allow for an error of roughly $189 million, according to the COGFA revenue estimate. That’s more than the entire proposed operating budget for the following agencies and offices:

- Office of the Governor ($4.7 million)

- Office of the Lieutenant Governor ($1.2 million)

- Office of Executive Inspector General ($7.7 million)

- State Board of Elections ($25.4 million)

- Department of Human Rights ($15.1 million)

- Department of Insurance ($48.7 million)

- Department of Labor ($12.8 million)

- Department of Military Affairs ($64.6 million)

If revenue comes in below projections, that means adding to the backlog of bills, which already stands at close to $6.9 billion as of May 9.

Ultimately, Illinois’ poor budgeting basics – exemplified by Cullerton’s remarks on adopting a revenue estimate – cause uncertainty. This uncertainty is a leading cause of Illinois’ poor credit rating.

While some starting point is certainly better than none, there’s an even better option for lawmakers than unreliable revenue estimates. Instead of continuing to play political games, voluntarily adopting a spending cap for this year’s budget would give lawmakers a reliable “magic number” around which to plan the budget.