Border war: In Quad Cities, Illinois shrinks as Iowa grows

The Quad Cities are a case study in how the Land of Lincoln is lagging behind its neighbors.

The Quad Cities region, stretching across the Illinois-Iowa border, is a prime example of Illinois’ failure to keep up with neighboring states.

Government data show the Land of Lincoln’s side of the Mississippi River – which includes the cities of Rock Island, Moline and East Moline – is struggling to keep up with the Iowa side, which includes Davenport and Bettendorf.

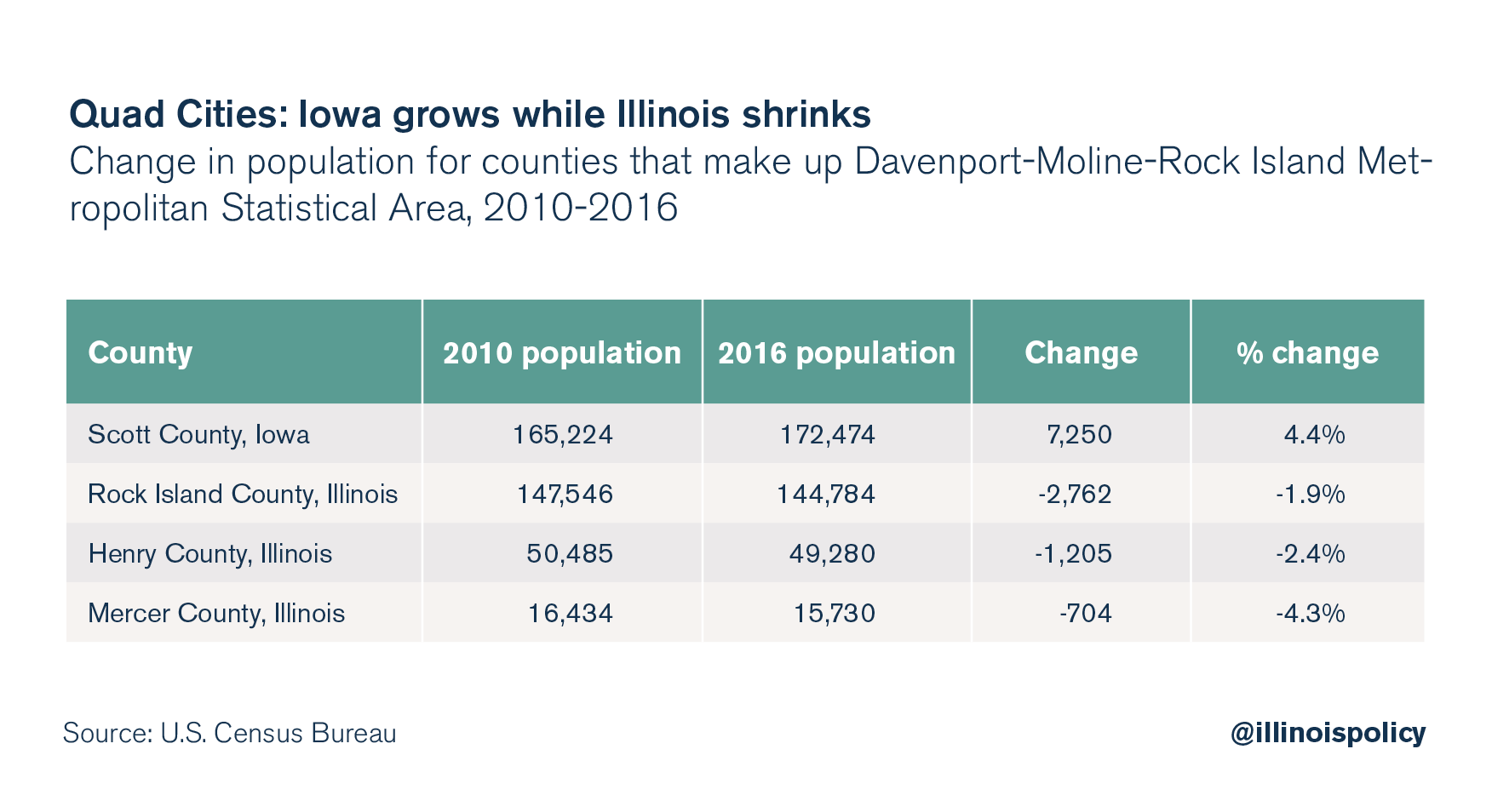

The Quad Cities make up what’s called the Davenport-Moline-Rock Island Metropolitan Statistical Area, which stretches across three counties in Illinois: Rock Island, Henry and Mercer. The Iowa side is concentrated in one county: Scott.

From 2010 to 2016, the most recent year of available data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the divergence is clear.

Rock Island County’s population shrank by nearly 2,800 people over that time, a 1.9 percent drop. Henry County fared even worse, losing more than 1,200 people, a 2.4 percent decline. Mercer County shrank by about 700 people, or a 4.3 percent decline.

But Scott County grew by more than 7,200 people, an increase of 4.4 percent.

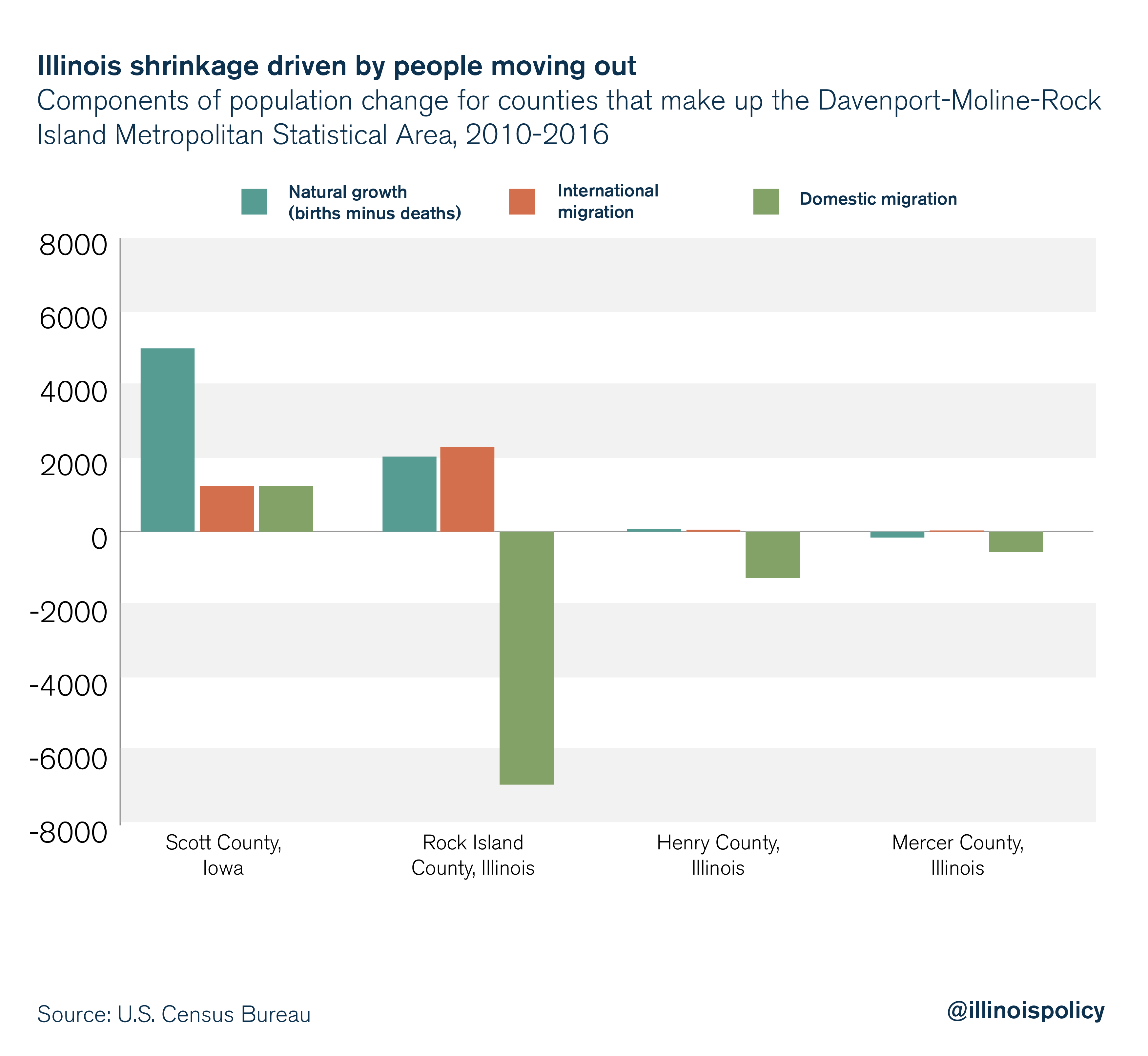

So what’s driving shrinkage on the Illinois side? People moving out. Mercer (losing a net of 564 residents), Henry (-1,244) and Rock Island (-6,891) counties all saw more people move out to other counties than move in from other counties.

At the same time, Scott County enjoyed an influx of 1,244 residents on net from other counties, as well as nearly 5,000 residents due to natural growth (births minus deaths). Rock Island County enjoyed modest natural growth, but that was completely wiped out due to outmigration.

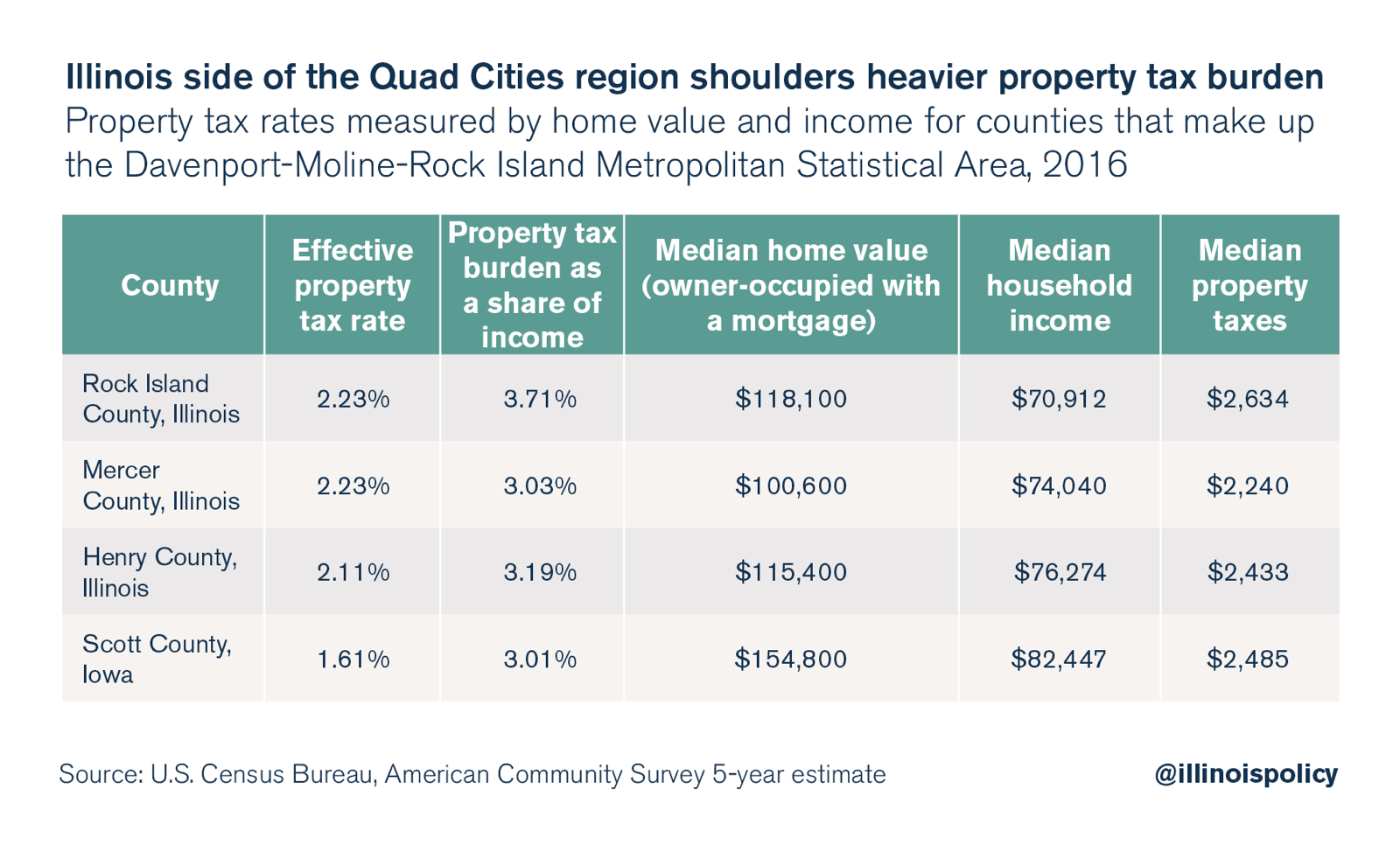

One policy choice that puts the Illinois side of the border at a disadvantage is residents’ high property tax burden. The difference between Rock Island County and Scott County is particularly stark, when looking at the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

While the median home value in Scott County is 31 percent higher than the median home value in Rock Island County, the median property tax bill is 6 percent lower. Measured as a share of residents’ income, Rock Island County’s property tax burden is 39 percent higher than Scott County’s.

Unfortunately, efforts to address the cost-drivers of those bills have too often been “hijacked” by those opposed to reform. In Henry County, for example, calls to study potential cost-saving measures among the dozens of different local governments across the county have been muzzled repeatedly.

And the Illinois General Assembly has been unwilling to tackle a number of substantial, much-needed reforms to reduce property tax bills.

Meanwhile, the Hawkeye State is moving ahead with reforms to poach more Illinoisans. For example, Iowa changed its rules for government union collective bargaining in 2017. This will help Iowa control taxpayer costs and keep down their property tax burden, while Illinois property taxes continue to spin out of control.

Until Springfield takes smart steps toward making the Land of Lincoln more attractive for families and businesses, Illinoisans shouldn’t expect to win out against neighboring states.