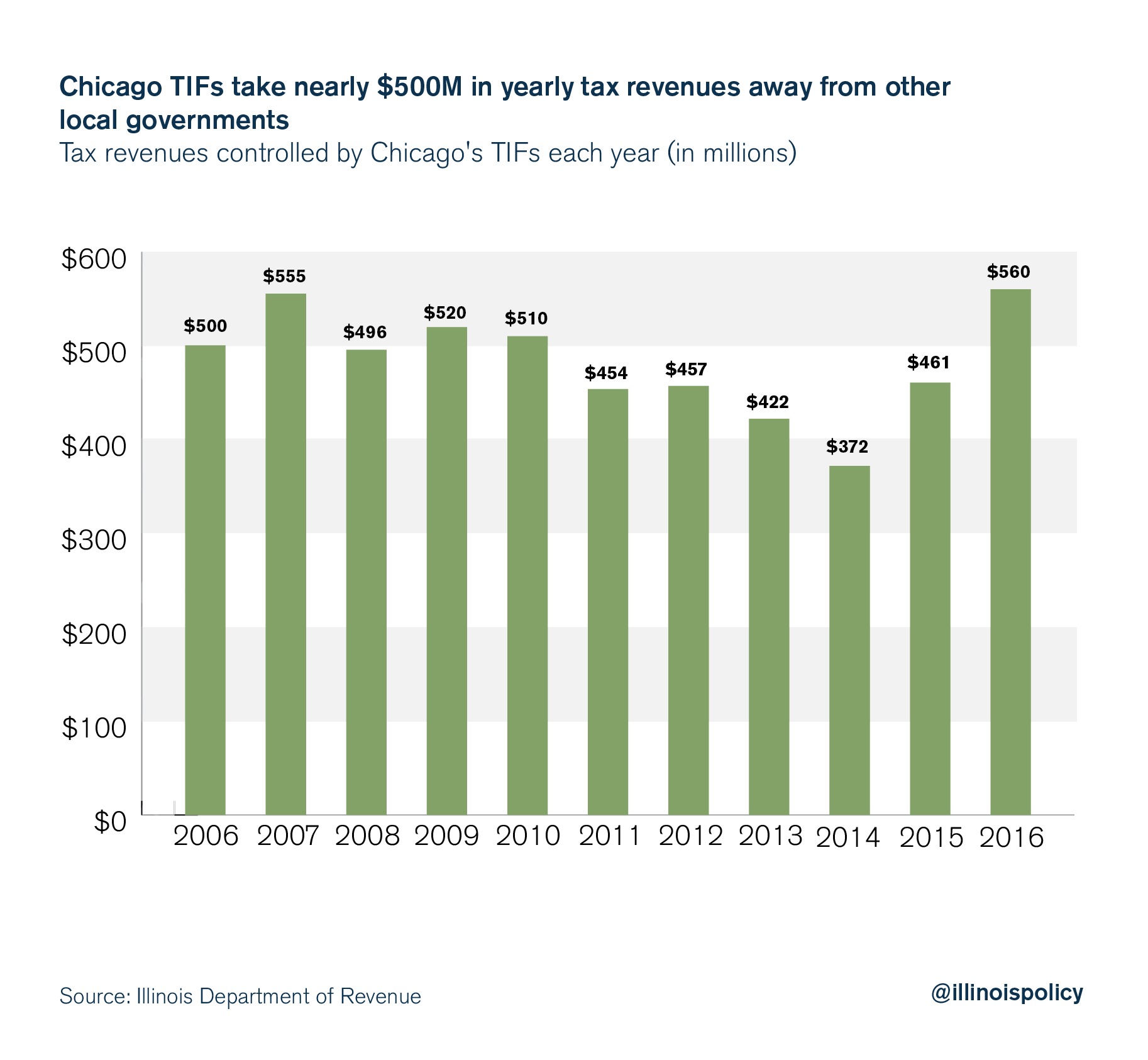

Chicago TIFs take nearly $500M in yearly tax revenues away from other local governments

Since 2006, Chicago Public Schools has been deprived of $2.5 billion in property tax revenue that has been diverted to Chicago TIF districts.

There are only a handful of policy issues in Chicago that draw the ire of all sides of the political spectrum. Tax increment financing, or TIF, is one of them.

TIF districts, the name given to special economic development zones, are controversial across the country. In Chicago, this system takes $500 million in taxpayer dollars that would otherwise be available to schools and parks and shifts them to a special fund controlled by Mayor Rahm Emanuel. The mayor doles out those funds to private developers to “incentivize” development in areas that are deemed blighted.

The Chicago Teachers Union has fought relentlessly to “free the funds” locked up in TIFs so Chicago Public Schools can access them. In an article in the Chicago Reader, Ben Joravsky described TIFs as a “shadow budget” forged behind closed doors. The Better Government Association and Crain’s Chicago Business recently exposed the shell games played with $55 million in TIF funds at Navy Pier, one of the city’s most popular tourist destinations.

And the Illinois Policy Institute opposes TIFs because they sap other local governments of property tax revenue. The relationship between Chicago Public Schools and TIFs is evidence of that.

TIFs need to go.

TIFs sap local governments

For too long TIFs have been supported under the premise they fight neighborhood blight – that economic development would not happen “but for” the creation of TIFs.

But to create TIFs and to ensure Emanuel has money to spur development, other local governments such as CPS have to do without the incremental property tax revenue generated within the designated development area for a period of 23 years.

Those rules have given Emanuel, and before him, Mayor Richard M. Daley, control over nearly $500 million in TIF tax revenues yearly over the past 11 years, for a total of more than $5.3 billion.

For CPS, which typically takes in just over 50 percent of the city’s property taxes, that’s meant more than $2.5 billion in foregone local tax revenues for its students over that same period.

To generate that kind of tax revenue annually, Chicago TIFs control about 10 percent of the city’s property value. That includes properties in the Loop such as LaSalle/Central and Randolph/Wells, areas that today are anything but blighted.

As recently as 2007, before the Great Recession, Chicago TIFs controlled more than $11 billion in property. In 2015, the most recent year available, Chicago had $6.6 billion of property value, or equalized assessed value, in TIFs, which equals roughly 10 percent of the city’s total $67 billion in equalized assessed value.

TIF properties also generate more revenues for development because they are not subject to property tax cap laws. The yearly property tax revenue for CPS, for example, can only grow by the lesser of inflation or 5 percent. But if those property values are part of the TIF, they are not subject to the property tax cap. And that means more money in TIF funds controlled by Chicago’s mayor.

Chicago Public Schools

Much of the recent controversy over TIFs has arisen as CPS has hurtled toward bankruptcy. The school district’s credit is junk-rated, its pension system is only half funded, and its borrowing costs have skyrocketed.

The conflict over TIFs has also come to a head as proponents of school funding reform demand fairness in the state funding formula, especially for lower-income children and areas with high concentrations of poverty.

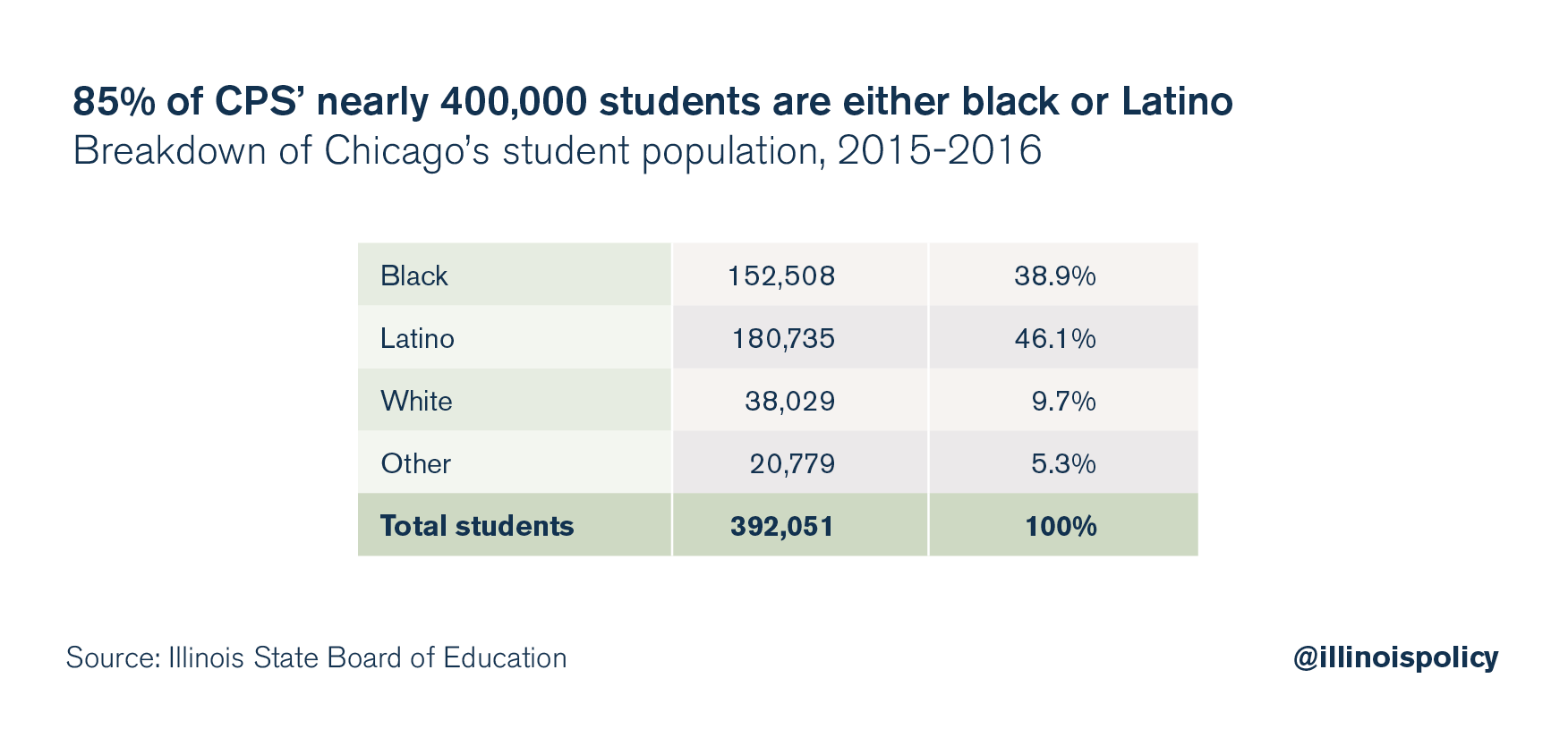

CPS, in particular, is affected by TIFs. Nearly 87 percent of CPS’ student population is included in the poverty count for school funding purposes, according to school district data.

Additionally, as 85 percent of CPS students are black or Latino, Chicago’s TIFs also have a disproportionate impact on funding for minority students.

The money TIFs siphon away from children and toward developers is in direct contradiction to the stated goals of Illinois’ education finance formulas.

The state education funding formula does attempt to compensate school districts subject to TIFs, but that ends up creating a shell game that ruins the original intent of the funding formula.

Providing subsidies to school districts subject to TIFs creates an uneven process that punishes districts without TIFs.

Ending TIFs

Proponents of TIFs continue to defend the practice and the oversized control by the mayor over billions in taxpayer funds.

But TIFs are controversial nationwide, and their benefits are suspect, at best.

The negative impact TIFs have on the budgets of other local governments is often ignored.

And the presumption that there would have been no growth or redevelopment without TIFs – the “but for” argument – is just that, a presumption. In fact, in many cases it’s likely that TIFs only shift development that would have happened in another area to the TIF district, leaving the city no better off.

In addition, there is nothing to prevent cities from spending the money on more normal budget items and other government entities. Chicago is particularly guilty of this. In years past the city has sent surplus TIF money to fund CPS projects. Why divert money away from CPS – and the traditional budgeting process – in the first place?

The TIF program also lends itself to picking winners and losers – and not just between connected developers. The fight over TIFs pits Chicago politicians against each other in disputes over who gets even small slices of the program’s funds. This is all to the advantage of Emanuel, who chooses which aldermen to shower with TIF-funded projects.

Chicago has a notorious history of corruption. Allowing a slush fund that’s not subject to the same transparency as funds in the regular budget is begging for a mess. Which is exactly what Chicago is in.

TIFs are simply too easy to manipulate. Their benefits are too dubious. And they deprive Chicago students of education funding.

It’s time to end TIFs.