‘Evidence-based’ education funding doesn’t work, would cost Illinois taxpayers billions

An education-funding plan in the General Assembly is already proven to make unattainable goals at a high cost to taxpayers.

The Illinois General Assembly is ready to push forward an “evidence-based” funding program its supporters say will finally fix education and bring adequacy to education spending in Illinois. The spending program, which prescribes precisely how much Illinois should spend on everything from instructional materials to employee benefits, calls for an eventual $3.5 billion to $6 billion a year in additional taxpayer funding.

That’s a lot of money for a state that already spends far more per student on education than any other state in the Midwest and the 13th most in the nation. Illinois spends 40 percent more than Kentucky, 37 percent more than Indiana, 32 percent more than Missouri and 16 percent more than Wisconsin per student.

But more importantly, it’s a lot of money to spend on a program that doesn’t work.

The two creators of “evidenced-based” funding, professors Lawrence Picus of the University of Southern California and Allan Odden of the University of Wisconsin, have travelled across the country promising to dramatically improve student outcomes. In their pitch to the state of Washington, their evidence-based report “focused on identifying the resources needed by all schools to double student performance in the medium future.”

Those kind of claims – like doubling student performance – prompted Stanford University Professor Eric A. Hanushek to liken proponents of evidence-based funding with snake-oil salesmen. In “Confidence Men: Selling Adequacy, Making Millions,” Hanushek says “pity the poor states that actually implement the Picus and Odden plan. They are sure to be disappointed by the results, and most taxpayers (those who do not work for the schools) will be noticeably poorer.”

Reality bears that out. “Evidence-based” funding hasn’t worked.

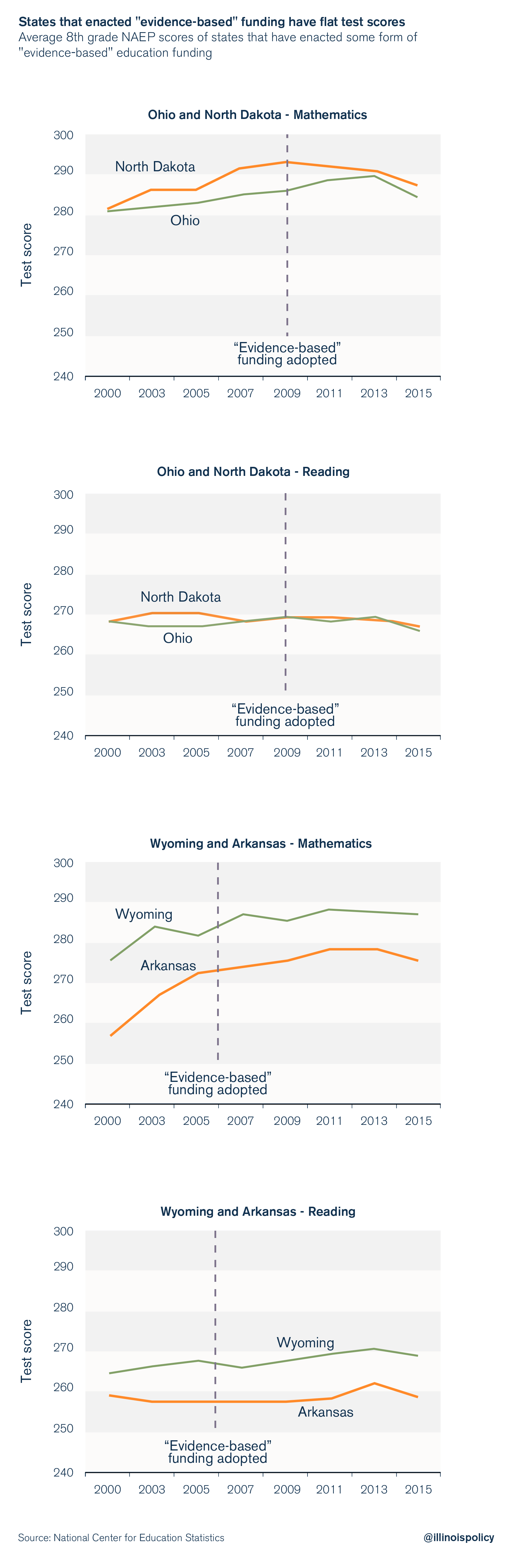

Ohio, North Dakota, Arkansas and Wyoming have all had “evidence-based” funding in place – some for up to a decade – and have collectively spent billions of additional dollars on select education programs.

In all those states, not only has student achievement on NAEP tests failed to grow at the rate the “evidence-based” funding model promises, but achievement has been virtually flat.

Proponents of “evidence-based” funding have cherry picked studies that have in some instances demonstrated improvements to student achievement – and have declared them all perfectly attainable.

Hanushek says Picus and Odden “provide ‘scientific evidence’ to support the claim that a specific set of policies can shift average student performance upward by three to six standard deviations, an extraordinary gain.” Later Hanushek says, “This, of course, is the stuff of science fiction novels, not research-based school policies.”

For comparison, Hanushek says one full standard deviation “is roughly equal to the average difference in test score performance between a 4th grader and an 8th grader,” which is a dramatic improvement by itself.

Claiming that specific spending can improve student performance by at least triple that, as “evidence-based” funding does, is an unrealistic end.

Common-sense solutions to education finance

The “evidence-based” funding model and its extravagant promises of student achievement is just an excuse to spend more.

As Hanushek told the Institute: “We know that focusing on input requirements for schools is a bad idea. If we want efficient and productive schools, we have to focus on the outcomes of schools and students.”

Lawmakers should apply a healthy dose of skepticism and reject the latest expensive formula promising to fix education. Increasing inputs – the funds Illinois spends on education annually – by billions is not the automatic solution to the education crisis.

Instead, making sure more of the money Illinois already spends on education actually makes it to students, as well as improving how that money is spent, is the key to improving education in Illinois.

Lawmakers can enact several common-sense reforms right now – highlighted in our report on education finance – that would ensure funding reaches Illinois students – all without demanding more from struggling taxpayers who already pay the highest property taxes in the nation.

Lawmakers would do well to start with freeing up the billions of education dollars consumed in pensions, the state’s nearly 900 school districts and the executive pay for those bureaucracies.

Until then, lawmakers shouldn’t hit up taxpayers for more. Instead, they should focus on getting better outcomes with what Illinois, the biggest education spender in the Midwest, already puts into education.