What Illinois college students should know before meeting with Rauner, lawmakers

What’s making college unaffordable for Illinois students isn’t budget gridlock, it’s soaring administrative costs in higher education.

Student body presidents representing some of Illinois’ largest universities and colleges are calling for a meeting to discuss the state’s higher education crisis with Gov. Bruce Rauner and the state’s legislative leaders – House Speaker Michael Madigan, House Republican Leader Jim Durkin, Senate President John Cullerton and Senate Republican Leader Christine Radogno.

The students are concerned about how the state’s continued budget impasse will affect students and families.

But before students get an audience with Illinois’ governor and legislative leaders, they should know the real reason for costly tuition and financial uncertainty isn’t the continued gridlock: University and college officials across the state have hiked tuitions to pay for massive administrative hiring sprees, executive compensation and out-of-control pensions.

A combination of those actions has pushed tuitions beyond the reach of Illinois’ students.

Politicians have for decades been complicit in making college unaffordable for way too many students, but the student leaders representing more than 200,000 of their peers shouldn’t focus squarely on the General Assembly, and their goal shouldn’t be to ask for more money from the state. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. Colleges and universities should get less money from the state. This would force them to roll back the administrative bloat and executive salaries they pass on to students. Only then can tuitions come down to levels Illinois students can afford.

Here are some of the most important things students should know as they prepare for their meetings.

The problem: A majority of higher education dollars are used for growing administrative staffs and pension costs

Illinois’ college and university officials blame the state’s budget crisis for the mess in higher education.

But budget gridlock isn’t why Illinois’ higher education system is facing troubles. Instead, it’s the growing number of administrators and the ballooning costs associated with them that are making college unaffordable for too many of Illinois’ students, especially those with limited means.

Rather than using state-collected taxes to keep tuition low, Illinois colleges and universities have taken an influx of federal and state funding available to higher education over the past two decades and spent it on a massive increase in administrative positions and exorbitant executive compensation.

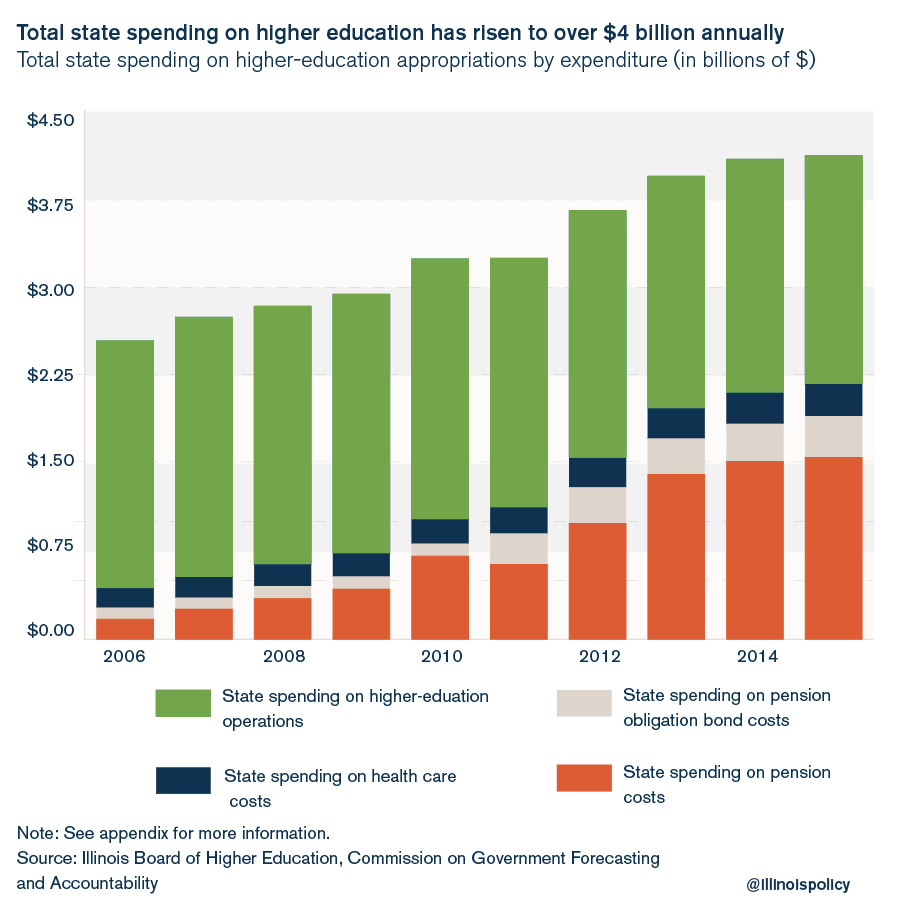

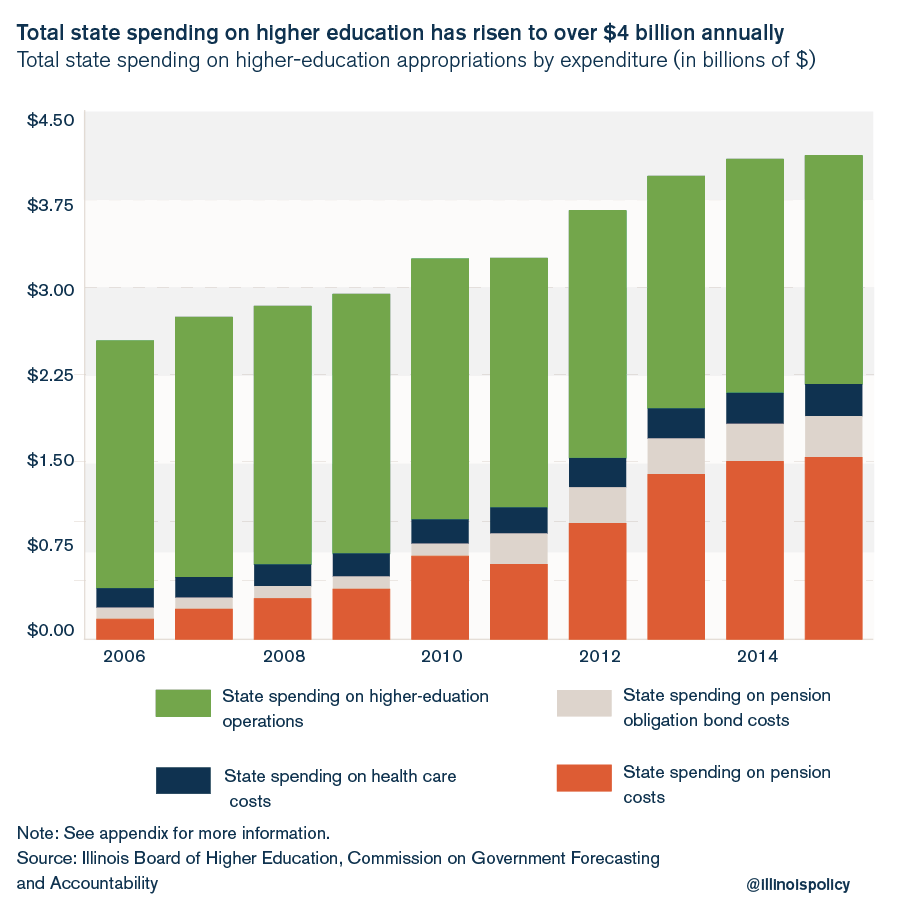

Illinois spends more money on administrative and retirement costs than on university operations. In fact, more than 50 percent of Illinois’ $4.1 billion budget for state universities is spent on retirement costs.

If this trend continues, students with the means will continue to leave Illinois for neighboring states’ colleges and universities, while lower-income students will increasingly be shut out.

More and more administrators

Over the past several decades, Illinois’ public colleges and universities have gone on an administrative hiring spree. They’ve grown the size of the higher education bureaucracy in Illinois while hiking tuition and spending state money to offset the cost.

According to the Illinois State Senate Democratic Caucus’ report, the rate at which colleges and universities across the nation are hiring administrators far outpaces the hiring of professors: “The disproportionate increase in the number of employees hired by colleges and universities to manage or administer people, programs and regulations has continued unabated in recent years, increasing 50 percent faster than the number of instructors between 2001 and 2011.”

Illinois has followed that pattern. The number of administrators in Illinois’ universities grew by nearly a third (31.1 percent) between 2004 and 2010. At the same time, faculty only increased 1.8 percent, and the number of students only grew 2.3 percent.

At community colleges in Illinois, the number of administrators grew 13.5 percent while the number of faculty and students grew 6.8 percent and 3.9 percent, respectively.

In 1975, the administrator-to-student ratio for higher education institutions nationally was one administrator for every 84 students.

By comparison, in Illinois that ratio was approximately 1-to-45 in 2011.

Growing administrative costs

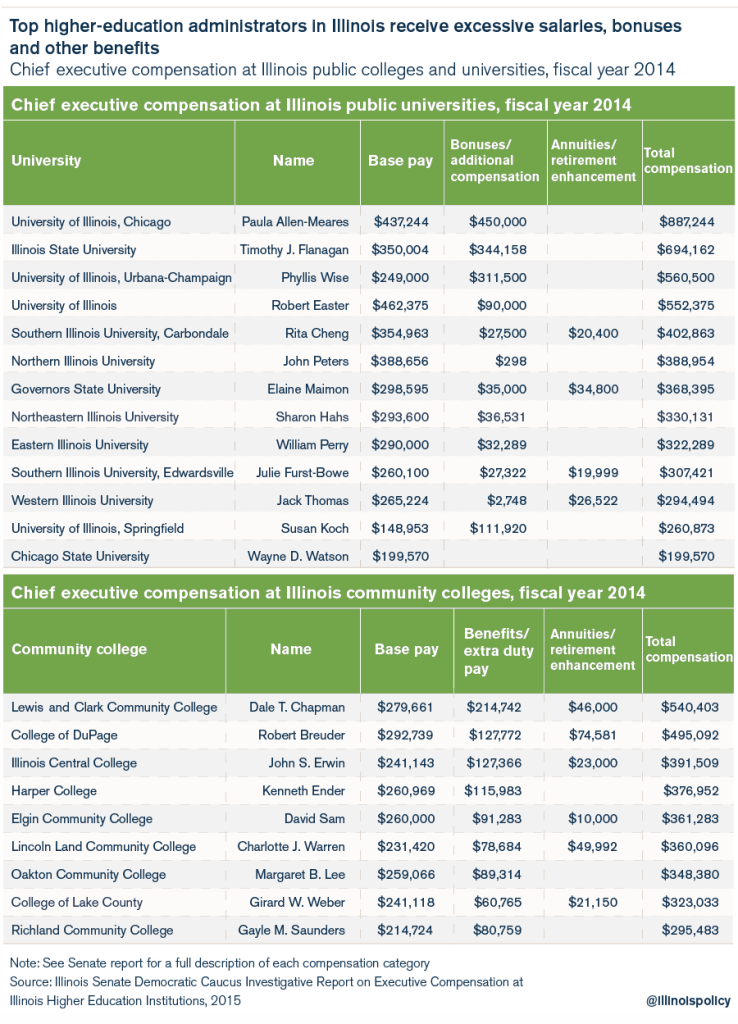

Not only have colleges and universities massively expanded their number of administrators, but they have also been paying those administrators exorbitant salaries. According to the Illinois Board of Higher Education, over half of Illinois’ 2,465 university administrators received a base salary of $100,000 or more in 2015. Ninety-five percent of the University of Illinois system’s top 126 administrators made $100,000 or more as a base salary.

Many top administrators also receive other perks such as housing allowances, cars, club memberships and generous bonuses that can cost universities hundreds of thousands of additional dollars per administrator.

The top-compensated administrator in 2014, the University of Illinois’ Chancellor Paula Allen-Meares, received much of her total compensation in the form of a bonus. Allen-Meares received a base salary of $437,244 and a bonus retention incentive of $450,000, bringing her annual compensation to $887,244.

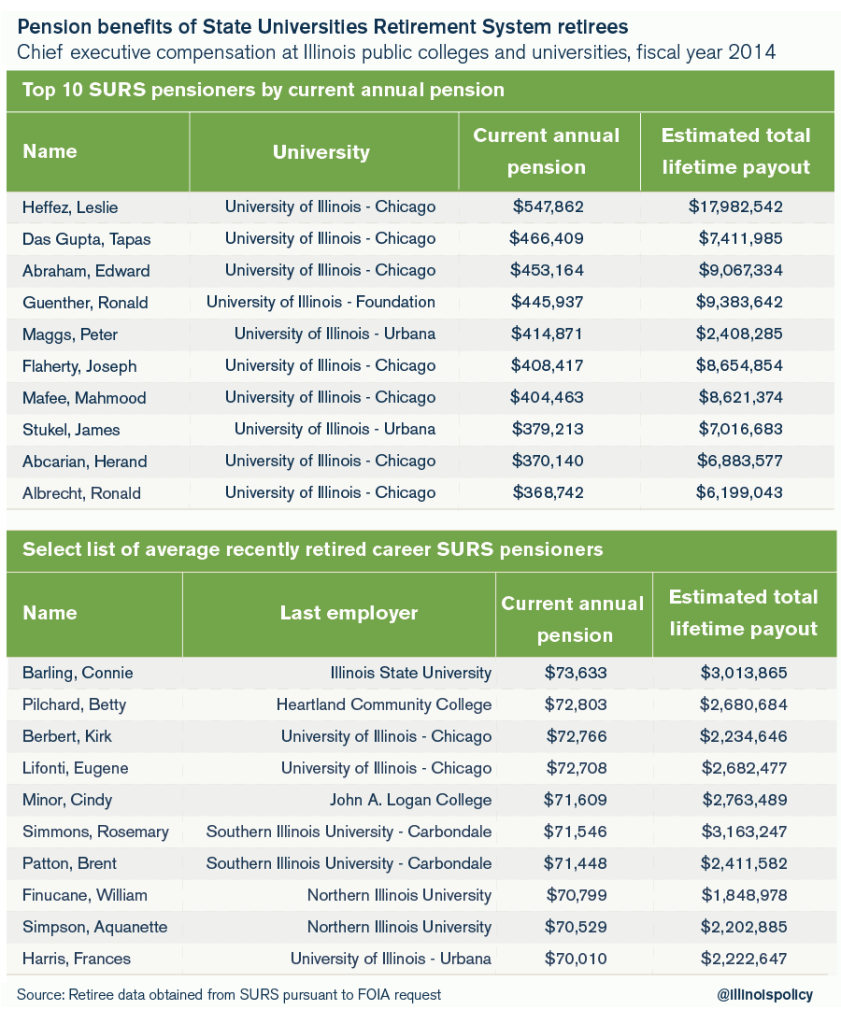

The enormous salaries university administrators and other employees receive not only increase expenses for colleges and universities, but directly contribute to the growing costs of university pension benefits for which state taxpayers are responsible.

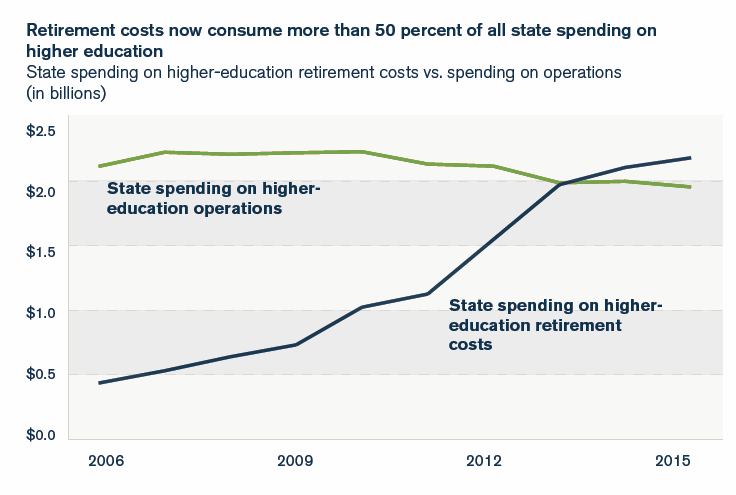

A decade ago, retirement costs made up only 20 percent of the state’s total higher education spending. Today, that figure has ballooned to 53 percent. As spending on retirement rose from 2006 to 2015, state spending on higher education operations fell by over $150 million. Higher education costs are out of control in many states, but Illinois adds an untenable pension crisis to the mix of too many administrators and too much budget bloat.

Because university retirees’ annual pension benefits are determined in part by their annual average salaries, large salary increases, coupled with generous pension rules, have boosted the retirement benefits of university employees far beyond what state taxpayers can afford.

Of the over 52,000 current State Universities Retirement System retirees:

- 50 percent retired in their 50s, many with full pension benefits.

- Almost half will see their annual pension benefits double over the course of their retirement, based on approximate life expectancies.

- Over 40 percent will receive more than $1 million in total retirement benefits, and over 7,400 (14 percent) will receive more than $2 million in benefits.

The retirement experience of an average, recently retired career university employee (retired since Jan. 1, 2013, with 30 years of service or more) demonstrates how the politician-granted benefits boost retirees’ pensions. For example, Betty Pilchard, a professor who retired from Heartland Community College in 2014 at age 58, received a starting annual pension benefit of $71,551.

By the time Pilchard reaches her approximate life expectancy of 84, her annual pension will have increased to $154,306 a year. This is because the 3 percent cost-of-living adjustment she receives every year causes her original $71,551 annual benefit to build upon itself, doubling Pilchard’s benefit in 25 years.

While administrator costs have skyrocketed, university officials have complained for years about the state’s lack of commitment to higher education, perpetuating a myth that the state’s appropriations have been in steady decline.

But state funding has increased by more than 60 percent over the last decade, growing to over $4.1 billion in 2015 from $2.5 billion in 2006. Unfortunately, a majority of that money has gone toward administrative salaries and retirement costs, not classroom instruction.

Tuition pays for too much administration

University officials have effectively shut the door for many of Illinois’ college-bound students through alarming tuition increases to pay for their growing executive salaries and benefits.

Faced with massive tuition hikes, students with the financial means choose to go to less expensive schools out of state while low-income families are stuck – unable to afford any college at all.

Overall enrollment for Chicago State University is down 25 percent from just last year. The 86 freshmen who registered in fall 2016 include both full-time and part-time students – smaller than the kindergarten classes at many Chicago public schools.

According to the Illinois Board of Higher Education, tuition has increased dramatically at Illinois’ public universities for more than a decade. Combined student tuition and fees grew anywhere from 74 to 112 percent between 2006 and 2016, depending on the university.

At the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the public university with the highest tuition and fee costs in the state, average tuition now costs $15,626 annually, up 80 percent since 2006.

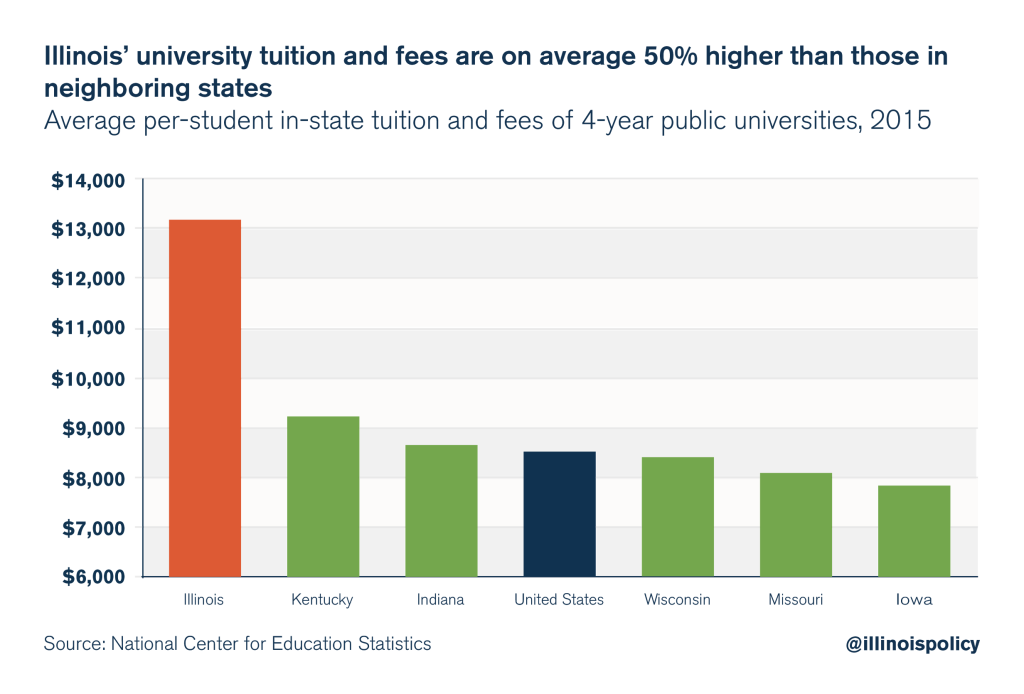

In fact, Illinois’ average in-state tuition and fees for four-year public universities is over $13,000. That’s 42 percent to 67 percent higher than the tuition in neighboring states.

Illinois universities should rely less on state funding because of the tuition they charge. But the opposite is true.

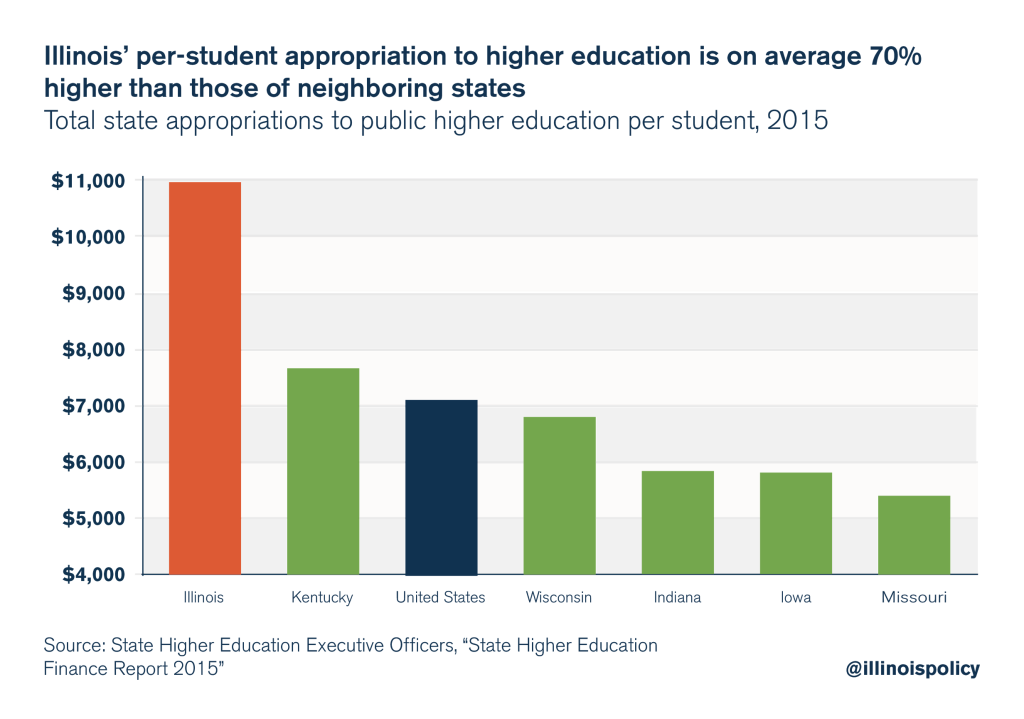

Illinois universities’ massive increase in administrative positions and exorbitant executive compensation over the past few decades has made higher education more reliant on state-provided dollars compared with universities in neighboring states.

The state of Illinois’ annual appropriation to higher education equals nearly $11,000 per student. That’s 70 percent higher than the average state-provided appropriations of Illinois’ neighbors.

So not only do Illinois universities charge the highest tuition in the region, they are also the most reliant on the state for financial support.

This double burden on Illinois families – high tuition paid by parents and students and high state support funded through taxes – cannot continue.

The solution: Prioritize students

Instead of letting Illinois’ higher education system deteriorate further, Illinois’ colleges and universities must first freeze and then begin to reduce the cost of tuition. They must reform their operational spending, reduce the cost of salaries, and eliminate administrative bloat – then pass the resulting savings on to students.

The state should reduce appropriations to colleges and universities by $500 million – the equivalent of approximately 10 percent of projected payroll costs in 2018. Until colleges and universities enact reforms, the destructive cycle of hiking tuition while relying increasingly on state subsidies will continue, making higher education less and less affordable for Illinois’ students and more and more expensive for state taxpayers.