Illinois now surrounded by Right-to-Work states

Missouri has become the 28th state to enact Right to Work, causing Illinois’ regional competitiveness to decline further.

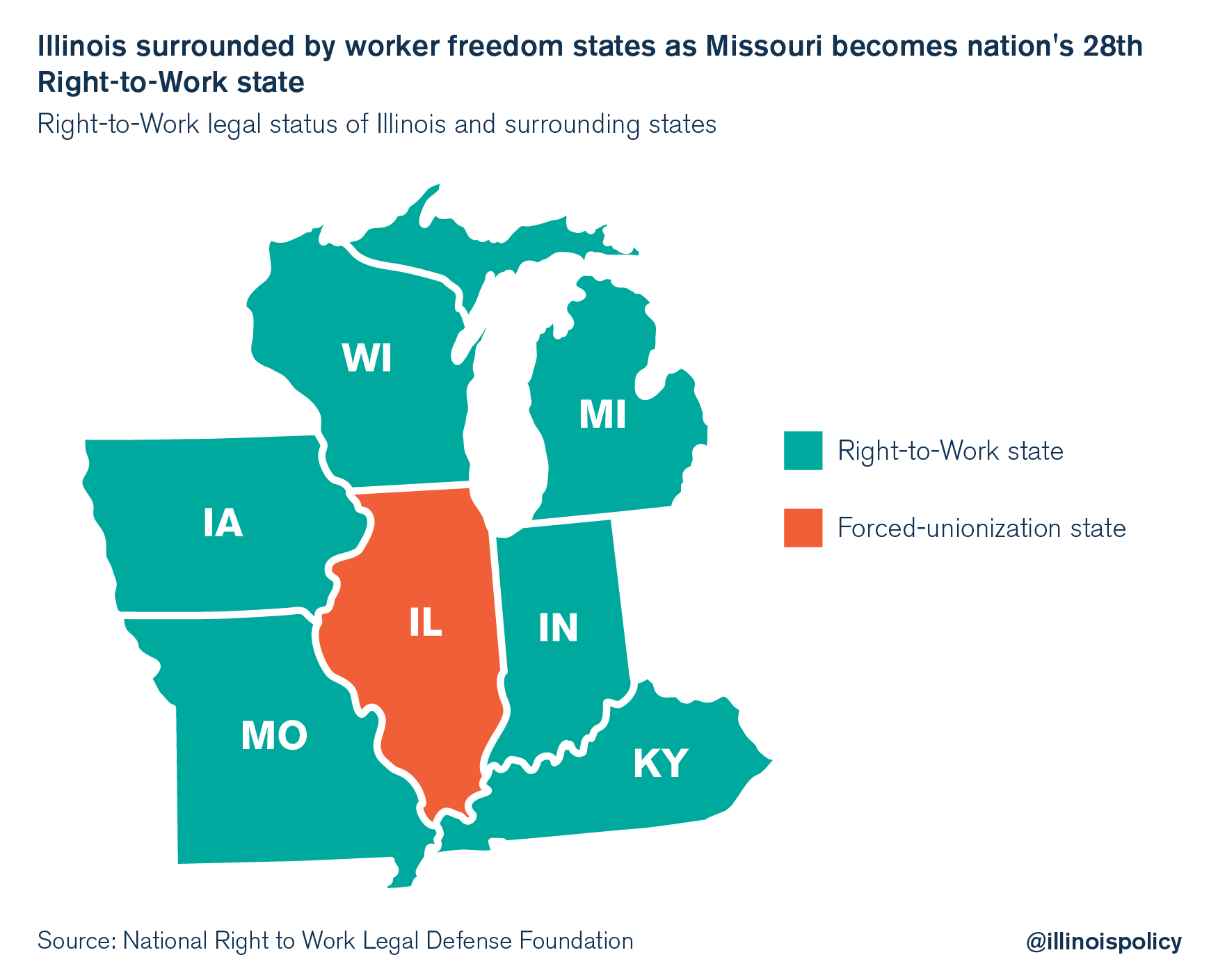

Missouri became the 28th Right-to-Work state in the U.S. as Gov. Eric Greitens signed Missouri’s Right-to-Work bill into law Feb. 6. Now, Missouri law protects a worker’s choice of whether to associate with a workplace union. Illinois is now the regional outlier, as its neighbors are all Right-to-Work states. The consequences of being left behind are playing out across Illinois, where job creation is stagnant and taxpayer costs associated with government unionization are soaring.

The Right-to-Work revolution began sweeping across the region five years ago, when then-Gov. Mitch Daniels signed Right to Work into law for Indiana. Prior to Indiana, the only Right-to-Work state in the region was Iowa, which enacted a Right-to-Work law in 1947. Indiana was soon followed by Michigan (2013), Wisconsin (2015), Kentucky (2017) and now Missouri.

Since 2012, states across the region have competed for middle-class jobs and industrial investment; Illinois, though, has made no improvements to its industrial regulations. Since the middle of 2012, Illinois has lost 20,500 manufacturing jobs, while Indiana has added 33,100. During this time Michigan has added 59,700; Wisconsin has added 16,400; Kentucky has added 16,800; and Missouri has added 6,700.

Illinois’ forced-unionization status has not helped protect union membership, either. The Bureau of Labor Statistics recently released a report on union membership by state. The report showed that in 2016, union membership fell by 35,000 in Illinois, compared with increases of 21,000 in Indiana, 3,000 in Kentucky, and 32,000 in Missouri. Michigan’s union membership decreased by 15,000, and Wisconsin’s fell by 4,000 over the past year. While union membership is declining in many places, Illinois’ experience shows that private-sector unions are especially unlikely to grow when industrial investment and demand for labor are weak.

Businesses certainly consider the Right-to-Work status of states when deciding on industrial expansions: Two-thirds of global chief financial officers surveyed by CNBC said a Right-to-Work law is either “important” or “very important” when they decide where to grow their businesses. This puts Illinois workers at a severe disadvantage for attracting job-creating investments. Over 1,100 businesses have black-listed Illinois because it is not a Right-to-Work state, according to Jim Schultz, the former director of the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity.

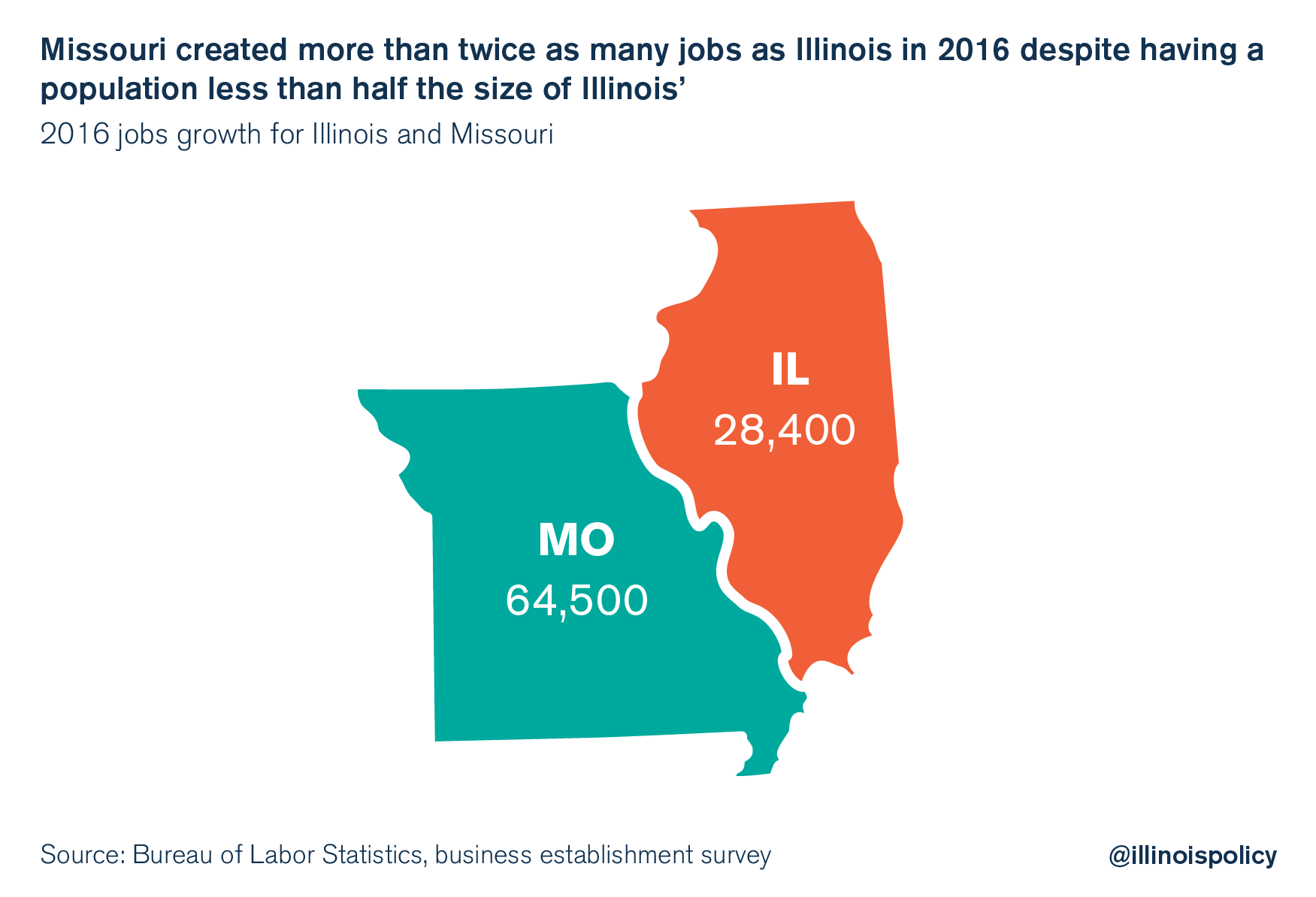

With Missouri’s new law, potential business investments that will lead to new blue-collar jobs are even less likely to end up in Illinois, and the trend is already working against the Land of Lincoln. In 2016, Missouri had one of the better jobs growth rates in the region, adding 64,500 jobs on the year. Illinois, on the other hand, gained just 28,400 jobs in 2016, the worst rate in the region.

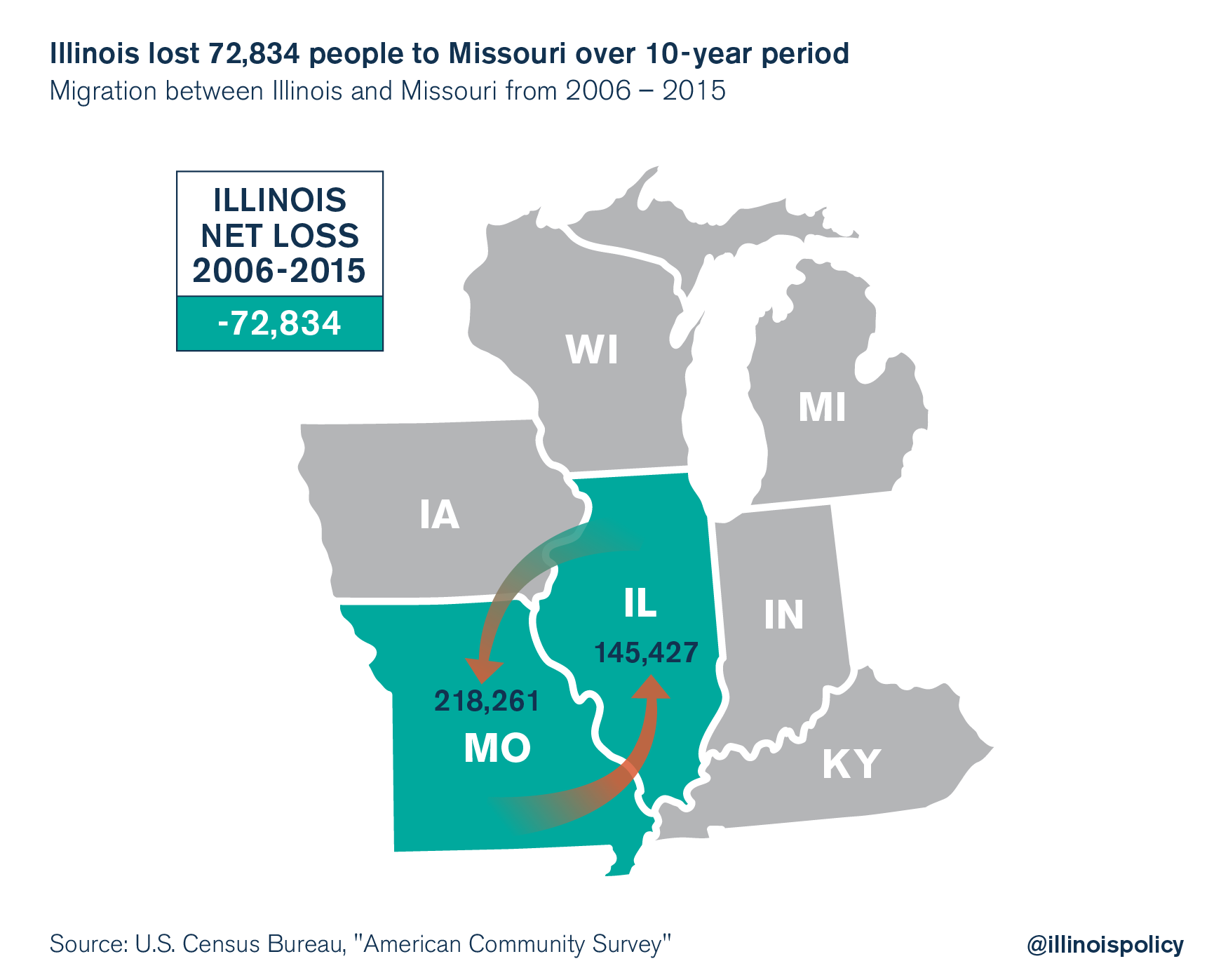

Illinoisans are likely to continue streaming across the Missouri border in search of more jobs and a lower cost of living. Over the past decade, nearly 220,000 Illinoisans have decamped for Missouri, while only 145,000 left Missouri for Illinois. The resulting loss of 73,000 people, on net, indicates that Illinoisans are voting with their feet to join the Show Me State. Missouri’s Right-to-Work law will likely make this trend worse for Illinois.

Illinois has become the regional outlier for labor law, and is now completely surrounded by Right-to-Work states. The state’s anachronistic labor law is hurting Illinois’ government finances and leaving its industrial economy stuck in the 20th century. Surrounding states, meanwhile, continue to make advances that will keep taxes low and job creation high. For policymakers, the choice is increasingly clear: Illinois can either enact reforms or continue watching its residents flee across the state’s borders for a net loss of more than 100,000 per year.