Illinois state workers have options if they wish to opt out of a union

Illinois state workers can opt out of union membership to become fair share payers, but reforms such as Right to Work and Worker’s Choice would promote greater worker freedom and benefit the state.

With a potential Illinois state workers’ strike on the horizon, unionized workers need to know some keys facts: They cannot be forced to maintain union membership in order to keep their jobs. And if they are not members, the union cannot penalize them in any way if they choose to work during the strike.

But the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees’ potential strike over its contract negotiations with the state also marks a harsh reality: Illinois lags behind many other states in promoting worker freedom.

In Illinois, state workers who wish to opt out of union membership only have only two options. If they object to union membership on the basis of religious belief, they can opt out of membership. But such workers are still required to pay fees – equal to the amount of union membership fees – to a nonreligious charitable organization.

The only other option is to become a fair share payer. As fair share payers, workers still pay fees – up to 100 percent the amount of union dues – to the union. These fees are supposed to represent the worker’s “fair share” of what it costs the union to represent workers in negotiating with the state.

But this means fair share payers are still forced to pay money to a union they may not even support. Union representation is forced on them, whether they want that representation or not. They are forced to accept whatever contract the union negotiates. And if the worker has any kind of problem at work, he must utilize the union’s grievance process in order to address it with the employer.

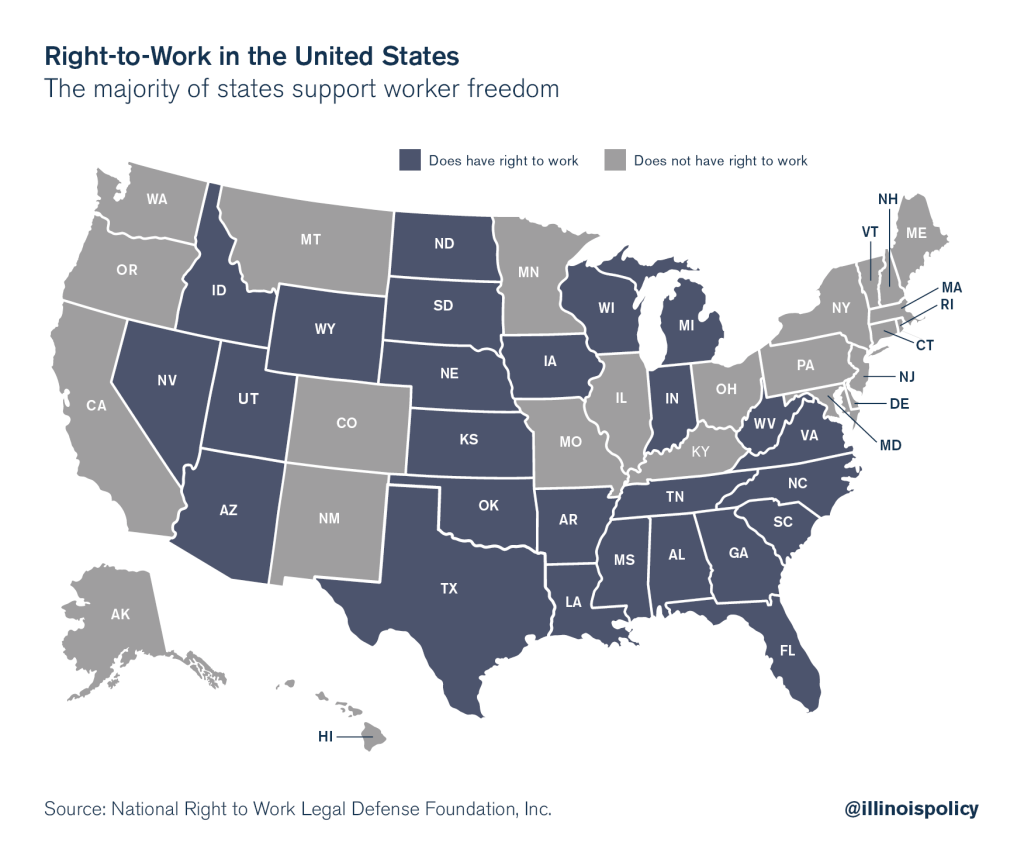

Workers in Illinois need more options. In more than half the states – including several of Illinois’ neighbors – workers have the freedom to opt out of union membership and out of paying union fees. Illinoisans, too, should have the freedom to decide with which groups they associate. They should have the right to choose whether to express support for a union by paying fees. No one should be forced to surrender First Amendment freedoms – freedom of association and freedom of speech – to keep a state job.

Illinois state workers could enjoy such freedoms – and the state could experience economic growth – if policymakers institute reforms such as Right to Work and Worker’s Choice.

Both options include benefits not only for workers, but also for taxpayers and even the unions themselves. Right to Work allows workers to opt out of union membership and fees, but the union still represents the workers. Worker’s Choice refers to a worker’s ability to opt out of union membership, union fees and union representation.

Right to Work allows workers to opt out of union membership and fees, but not out of union representation

The majority of states now have Right-to-Work laws, including several of Illinois’ neighbors. In Right-to-Work states, a worker can opt out of union membership

and opt out of financially supporting the union. No fair share fees are required.

Right to Work prohibits forcing workers to pay dues or fees to a union as a condition of keeping their jobs.

As with fair share payers, the union still represents workers who have opted out of union membership in a Right-to-Work state. But rather than paying fair share fees, these workers are not forced to pay any fees to the union. It is entirely up to the worker to decide whether he or she wants to join (and pay) the union.

Not only do Right-to-Work states better protect workers’ freedom, but a majority of Americans support Right-to-Work laws, and those laws have demonstrated positive economic results for states that have adopted such reforms.

In a 2014 Gallup poll, 71 percent of Americans polled stated they would vote for a Right-to-Work law, with just 22 percent stating they would vote against. The poll also found that 65 percent of Democrats and 74 percent of Republicans would vote for a Right-to-Work law.

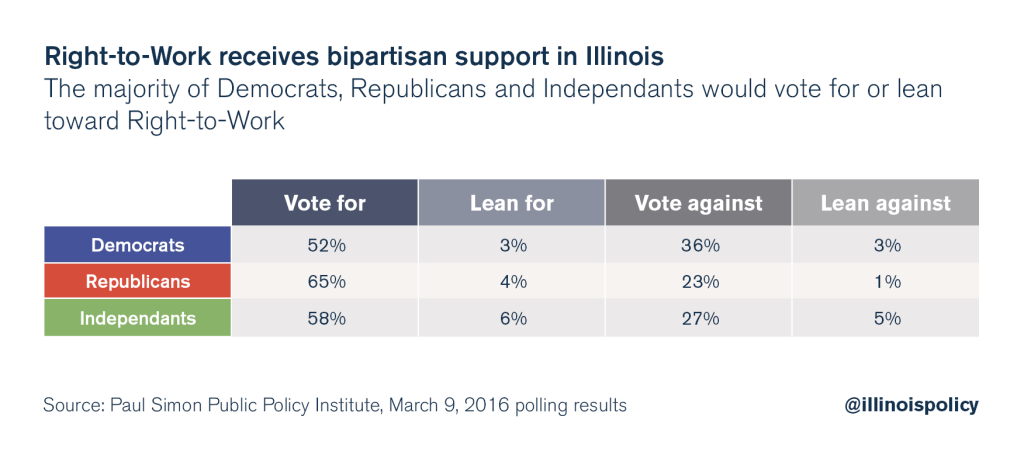

Likewise, a March, 9, 2016 Illinois-specific poll the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University conducted found 61 percent of Illinois voters would vote for, or lean toward voting for, a Right-to-Work law. And like the Gallup poll, the Paul Simon poll revealed support of Right-to-Work is bipartisan: 56 percent of Democrats and 69 percent of Republicans said they would vote for or lean toward supporting a Right-to-Work law.

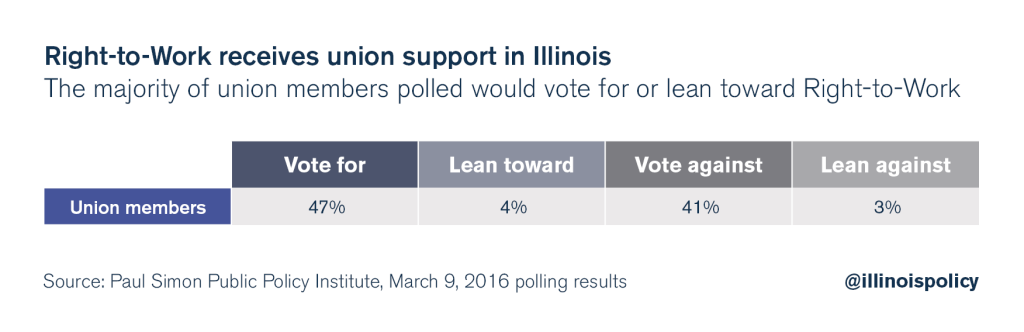

What’s more, 51 percent of union members in Illinois responded that they lean in favor of Right-to-Work laws.

And contrary to claims that Right-to-Work kills jobs and state economies, the evidence shows Right-to-Work states generate stronger economic growth – including among Illinois’ main competitors for business in the Midwest:

- Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics reveal average wages have increased in both Indiana and Michigan since those states enacted Right-to-Work laws in 2012.

- According to the U.S. Census Bureau, both Indiana and Michigan experienced population growth between July 2014 and July 2015. Illinois, on the other hand, was one of only seven states with population decline during that same time period.

- Forced-unionization states, including Illinois, lost1 million jobs between 2001 and 2011. Right-to-Work states, however, added 1.7 million jobs during this time – even as the Great Recession ravaged much of the country.

Not only does Right-to-Work strengthen state economies, but it can also strengthen unions. Union representation improves because unions must earn the dues of their members, rather than forcing members (or nonmembers) to pay no matter what.

Gary Casteel, secretary-treasurer for the United Auto Workers, said the following while he was in charge of organizing autoworkers in southern states:

“I’ve never understood [why] people think Right-to-Work hurts unions … To me, it helps them. You don’t have to belong if you don’t want to. So if I go to an organizing drive, I can tell these workers, ‘If you don’t like this arrangement, you don’t have to belong.’ Versus, ‘If we get 50 percent of you, then all of you have to belong, whether you like to or not.’ I don’t even like the way that sounds, because it’s a voluntary system, and if you don’t think the system’s earning its keep, then you don’t have to pay.”

But even in Right-to-Work states, the union still represents the worker in negotiations with the employer. That has caused some union supporters to criticize these workers for being “free riders.”

Ironically, unions – like AFSCME in Illinois – lobbied for the very laws giving them a monopoly to represent all workers. That monopoly requires unions to represent members and non-members alike.

So, contrary to union claims, these workers are actually “forced riders.” While they are not forced to pay fees to the union, they are still forced to accept union representation, regardless of whether they want that representation. And like fair share payers, they are forced to accept whatever contract the union negotiates.

Workers’ Choice allows workers to opt out of union membership, union fees and union representation

State workers should have the freedom to make decisions for themselves, including whether or not to join, pay or be represented by a union.

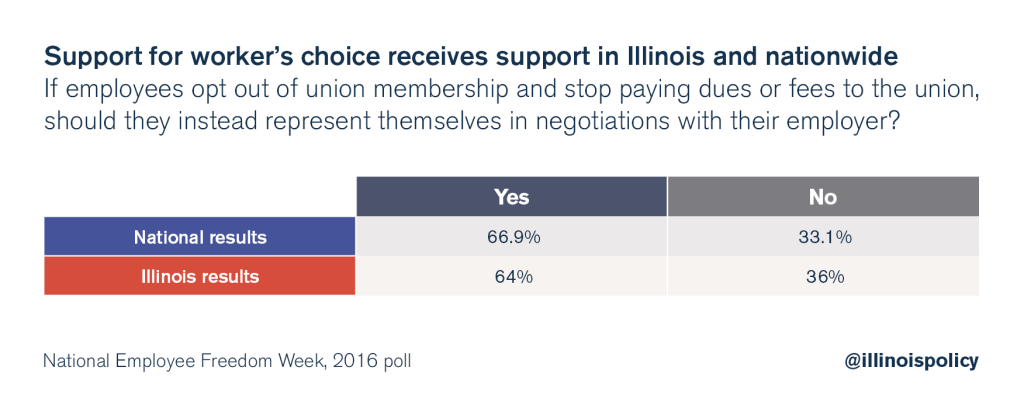

A 2016 poll the National Employee Freedom Week campaign conducted indicates almost one in four Americans – including 64 percent of Illinoisans – think that employees who opt out of union membership, including the payment of fees, should represent themselves in negotiations with their employer.

This sort of arrangement – when an employee opts out of union membership, union dues and union representation – is known as “Worker’s Choice.” No states have yet enacted Worker’s Choice.

Worker’s Choice provides workers with two options: 1) become a member and accept all of the applicable union requirements, or 2) opt out of union representation altogether.

In other words, workers have the choice to either be represented by a union (and pay union membership fees), or not. Workers have complete freedom to make that decision for themselves.

Like Right-to-Work, Worker’s Choice does not upset the relationship a union has with a public employer. The union will continue to bargain and negotiate for all member employees. Nothing would change in terms of the union’s negotiations with the state on behalf of its members. Its members would continue to have all rights guaranteed to them under union contracts.

As such, Worker’s Choice carries all of the same benefits that accompany Right-to-Work laws. But it includes an additional element of worker freedom: an individual employee would be able to opt out of the union and negotiate pay, benefits and working conditions for himself. This eliminates unions’ “free rider” arguments because unions no longer negotiate on behalf of workers who have opted out of the union. Unions in a Worker’s Choice state would only represent union members.

Both Right-to-Work and Worker’s Choice would provide more freedom to Illinois workers than is currently available to them under state law. Pursuing such reforms would not only benefit state workers, but it could also help boost a state economy that is in dire need of assistance.