Chicagoans on the hook for $34B in debt from city’s 4 pension funds

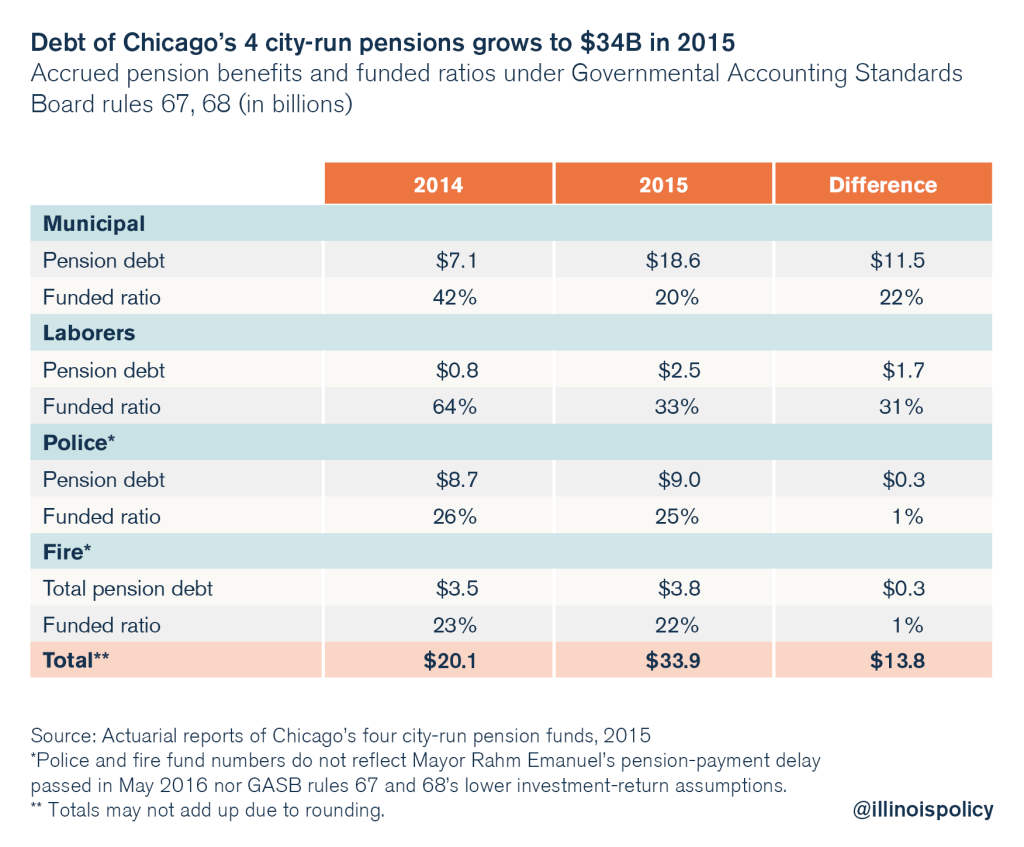

Chicago’s pension funds’ debt grew by two-thirds to $34 billion in 2015. That’s $33,000 of pension debt per Chicago household.

Chicago households reeling from massive hikes in property-tax bills and the specter of new utility-tax increases have yet another burden to bear – even higher pension debt from the city’s four pension funds.

According to the 2015 actuarial reports of Chicago’s police, fire, municipal and laborers pension funds, the city’s total pension debt grew by two-thirds in one year. Chicagoans are now on the hook for $34 billion in city-run pension debt – or $33,000 per city household. That doesn’t include billions in additional debt Chicagoans owe to Chicago Public Schools and Cook County pensions. It also doesn’t include long-term and government-worker health care debt owed by the city, its sister governments and Cook County.

Each of Chicago’s fire and municipal funds now has less than a quarter of the money needed to pay out future benefits. Chicago’s laborers pension system is now only 33 percent funded, down from 64 percent funded in 2014. And the police fund is only a quarter funded.

By any measure, all four of Chicago’s pension funds are insolvent.

Even worse for Chicagoans, the city’s $34 billion pension debt will be even larger when the police and fire funds properly report their numbers.

The police and fire pension funds’ 2015 numbers don’t reflect the pension “fix” approved by the General Assembly in May, which allows Chicago to extend the timeline of its payments to the police and fire pension funds. The 15-year payment delay just kicks the city’s pension costs down the road again, but at a cost to taxpayers of an additional $18.6 billion over the next 40 years.

Nor have the police and fire funds fully enacted new government accounting standards as the municipal and laborers pension funds have. Those new rules demand pension funds use more realistic assumptions when estimating how much money they will earn on their investments. The adoption of the new standards caused the municipal and laborers funds’ debt to double.

Assuming those new accounting standards affect the city’s police and fire funds similarly, Chicagoans will actually be on the hook for at least $44 billion in pension debt from the city’s four pension funds, or more than $43,000 per household.

Chicago is finally being forced to be more realistic about its pension debt, yet, due to the underestimated police and fire numbers, city residents still don’t know the full extent of the burden city-worker pensions are imposing on them. This shows just how divorced from reality Chicago’s pension funds still are.

One thing is clear: Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s go-to solution, higher and higher taxes, cannot solve the city’s pension crisis.

Chicagoans already face the highest tax burden in Illinois. Taking even more money from city taxpayers will result in more and more residents leaving the city – especially when Chicagoans know their dollars won’t go toward new and improved services, but rather to pay off old debt.

Only bold reform can stabilize Chicago’s finances, protect city taxpayers, make government-worker retirements secure, and restore confidence in the city’s future.

Bold reform means being honest about the true amount of the city’s pension debt and overhauling pensions to provide new workers with 401(k)-style retirement plans and optional 401(k) plans for current workers.

And it means stopping the out-of-control spending that has led to the city’s growing debt burden and paying down existing debts in a responsible manner.

That’s the path to bring the cost of city governance down to a level Chicago taxpayers can afford.