Record sealing for Illinois ex-offenders offers a better shot at employment, second chance

An effective record-sealing policy can help nonviolent offenders find employment and stay away from crime.

Without a job, an ex-offender is likely to end up back behind bars. In fact, nearly 50 percent of ex-offenders return to prison within three years of release. But a study by the nonpartisan Urban Institute found that former offenders employed within two months of release were less likely to be incarcerated a year later.

One way to encourage ex-offender employment is to expand Illinois’ record-sealing law to allow most nonviolent offenders the chance to apply to have their criminal records sealed as soon as they successfully complete their prison sentences or parole. Today, a chance at a sealed record is incredibly limited, and offenders must wait years before they can even apply.

To be sure, criminal records can help employers assess the risk of hiring a job applicant. If someone was convicted of a crime in the past, an employer may think the applicant is likely to get in trouble in the future, or worse, pose a threat to colleagues or customers. Employers are right to be cautious in making hiring decisions.

On the other hand, criminal records punish people for past mistakes after they’ve completed their sentences and paid their debt to society. And as former offenders who find stable jobs are considerably less likely to return to crime, it’s in society’s interest to have as many former offenders as possible gainfully employed.

How can Illinois protect employers from risks, while encouraging employment among former offenders?

Expanding record sealing, which requires the consent of a judge, is one solution. This approach would allow Illinois to foster employment among former offenders while protecting public safety.

Record sealing restricts the ability to view a criminal record to law enforcement, employers in sensitive industries such as schools and financial institutions, and anyone with a court order allowing access to the record. It’s a more modest step than expungement, which completely clears a criminal record from someone’s history so that no one, including law enforcement and employers, can see it.

To seal his record, an offender has to petition the court where the state initially brought criminal charges. A judge reviews the application and considers factors such as the strength of the evidence supporting the conviction, the offender’s age and criminal and employment history, and the period of time between the crime and the petition for sealing. When the application is submitted, law enforcement – including the state’s attorney and the police agency that arrested the offender – are notified and given the chance to oppose the sealing if they think the offender poses a continuing risk to public safety.

The idea that former nonviolent offenders could limit viewing of their criminal records might worry some people. But sealing reform wouldn’t give anyone a pass for criminal behavior – anyone applying for sealing has already been punished through incarceration and probation or parole.

There are also safeguards in place to protect public safety. For example, financial-services firms need to know if prospective employees have committed any offenses related to fraud or embezzlement – and the law provides for banks to see this information, even if a record is sealed. Schools are another field of employment in which knowing someone’s background may be critical – and schools also have access to all criminal records, even if they are sealed. Additionally, a record can still be accessed through a court order if necessary.

Nationally, at least 18 other states besides Illinois permit sealing or expungement of misdemeanor or felony records for adults. New Hampshire, for example, allows nonviolent convictions to be annulled, but waiting times vary between one and 10 years, depending on the offense. Utah allows petitions for sealing felony records seven years after an offense, and Texas passed legislation in 2015 allowing first-time offenders to have their records sealed, as long as their offenses are nonviolent and nonsexual.

In fact, Illinois also has a limited sealing program, established by the Criminal Identification Act. But it’s limited to a few low-level Class 4 and Class 3 offenses – such as possession of cannabis and prostitution.

Illinois should improve its sealing program. Here are three reforms the state should make:

- First, lawmakers should expand eligibility to apply for record sealing to most nonviolent offenses below Class X, the most serious level of felony.

- Second, lawmakers should eliminate the time an ex-offender must wait to be eligible to apply for sealing. Since most relapse into crime happens in the first year after incarceration, it’s important that an offender have the chance to argue in front of a judge once his sentence has been completed – so he’ll be better positioned to find work as soon as possible.

- Third, the current law should be revised to presume that anyone with a nonviolent offense will be allowed to petition for record sealing unless the General Assembly chooses to specifically exclude that offense.

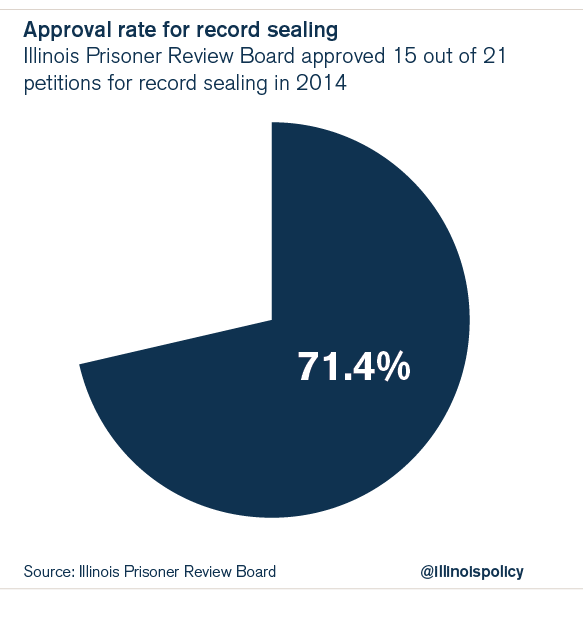

It’s not known exactly how many people in Illinois have sealed records today because data on sealing through the court system isn’t readily available. But some limited information regarding the frequency of sealing-petition approval does exist from the Illinois Prisoner Review Board, which can also issue certificates of sealing. In 2014, the review board received 21 petitions for sealing and granted 15, or 71.4 percent, of them.

Admittedly, only a small number of sealing petitions go through the review board. But the approval rate shows that a genuine vetting process occurs for sealing applications – not everyone who applies is successful.

Criminal records affect the employment prospects of a large part of the U.S. population. Over 65 million adults have a criminal record, according to the National Employment Law Project. Government’s ability to define someone by his past once he has already paid his debt to society should be limited. The careful expansion of sealing can help achieve this goal.