Chicago students receive more state funding than the average Illinois student

Chicago Public Schools CEO Forrest Claypool has claimed that Chicago students are discriminated against under the state's education funding formula. But the numbers show the opposite: Chicago has received more than its fair share of education funding from the state.

Chicago Public Schools, or CPS, CEO Forrest Claypool is trying to guilt the state of Illinois into a massive bailout of the broke school district. To do this, he’s using divisive rhetoric, even implying that the state’s education funding system is racist.

The problem with Claypool’s argument is that his numbers don’t add up.

Claypool claims that CPS only receives 15 percent of total state aid, even though it has 20 percent of the state’s total student enrollment. He also says that state education funding for Chicago has declined over the past several years.

Claypool’s solution is to demand a 20-20 “fair share” of state funding: If Chicago has 20 percent of Illinois’ students, then it should get 20 percent of the state’s funding.

But even a cursory look at the data over the last decade shows that rather than suffering discrimination, Chicago has received more than its fair share of education funding from the state – and then some.

Claypool’s claims are all part of an attempt to deflect blame from Chicago officials who have spent decades mismanaging CPS’ finances. CPS is nearing complete financial collapse. The district is currently saddled with multiyear billion-dollar deficits, a junk credit rating, and a pension plan that’s only half-funded. These drastic outcomes are the result of the district:

- Spending more than $1.2 billion on teacher pension pickups over the last decade

- Enacting pension holidays, which diverted almost $3 billion intended to fund pensions towards school salaries instead

- Hiking teacher salaries by 80 percent since 1998, resulting in Chicago teachers receiving the highest lifetime salaries in the nation compared with the largest school districts in the U.S.

- Allowing accrued teacher pension benefits to grow by 400 percent since 1987

In short, CPS officials need a scapegoat for the mess they’ve created – so they’re blaming the state for their self-inflicted woes.

But Chicagoans and Illinoisans across the state should not buy in to CPS officials’ deceptions.

The truth is, state spending on CPS has consistently grown over the past decade and a half. And under Claypool’s own metrics, Chicago has been a winner in terms of state funding. Over the last 10 years, when all state spending on education, including state contributions to pensions, is totaled, Chicago received more in state funding than it would have received under Claypool’s methodology.

The state’s education funding formula, which is used to redistribute local property taxes to school districts across the state based on need, has unfairly benefited Chicago at the expense of other districts for years.

Claypool has ignored these facts and perpetuated four myths about the state’s funding of CPS.

Myth No. 1: The state’s education funding formulas consistently shortchange CPS students. According to Claypool, “Our kids are being discriminated against in a radical, radical way. That is a type of system you would expect to see in Mississippi in 1896, not a great state like Illinois.”

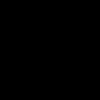

Fact: State education funding formulas (excluding pensions) have overwhelmingly favored CPS over the past decade.

The General State Aid, or GSA, program is the state’s largest single education appropriation for K-12 education. GSA distributes state money to local districts through funding formulas designed to grant more dollars to poor districts that don’t have the local funding necessary to educate students on their own.

The funding formulas that distribute state education funding – including GSA and categorical grants such as those for special education and transportation, but excluding state teacher pension contributions – have consistently favored CPS.

CPS has received more than 25 percent of the state’s education funding formulas over the last decade, despite the district’s share of total state enrollment hovering around 19 percent.

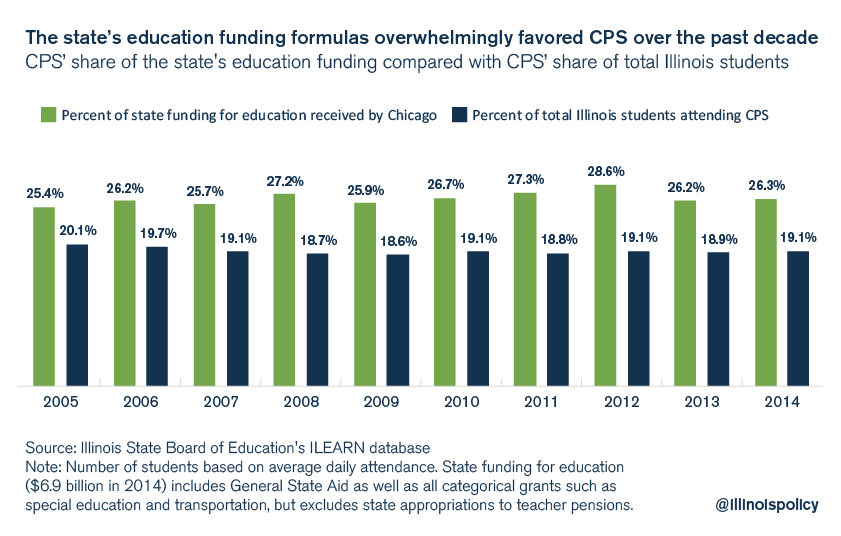

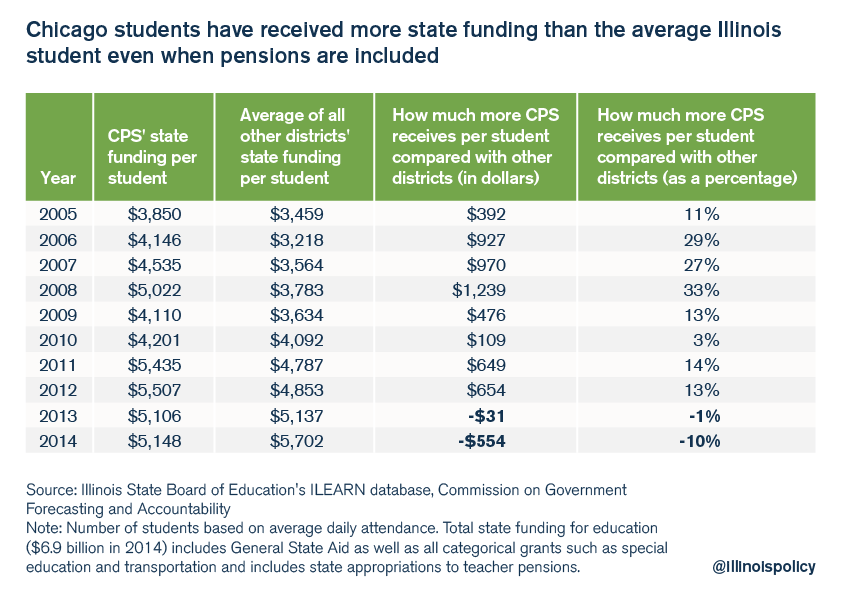

And when measured in dollar terms, CPS has consistently received more state money per student than the average Illinois district.

According to the Illinois State Board of Education’s ILEARN database, Illinois’ state government distributed nearly $7 billion from state income taxes in 2014, excluding pension contributions, to supplement local spending on education. On average, the state doled out nearly $3,414 per student in districts other than Chicago in 2014.

At $5,148 per student, CPS received far more state funding.

Over the past decade, CPS received an average of $1,630 more funding per student yearly when compared with districts across the rest of the state. Depending on the year, Chicago received anywhere from 35 to 69 percent more state funds per student.

Myth No. 2: Chicago’s low-income students are not getting the state support they deserve. According to Claypool, “90 percent of CPS’ students are from low-income families. … Yet, because of the broken school funding formula, these kids are not getting the resources they need.”

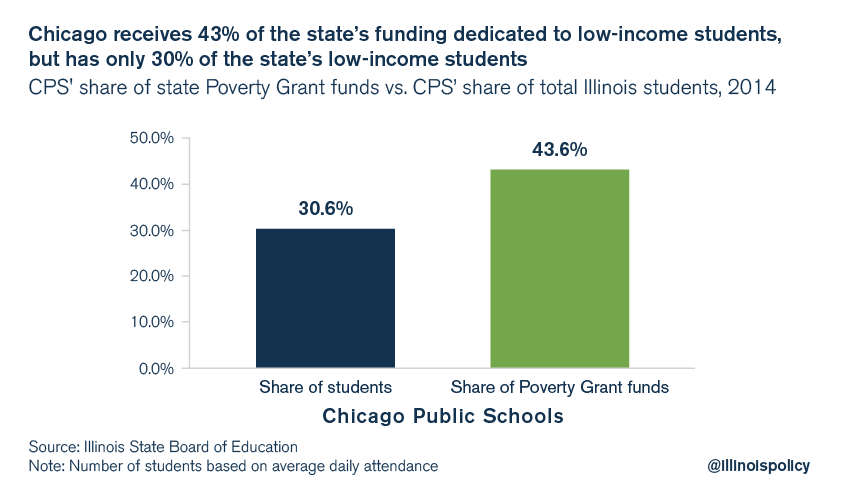

Fact: CPS receives more than 43 percent of the $1.9 billion dedicated to low-income students statewide, yet CPS has only 30 percent of the state’s low-income student population.

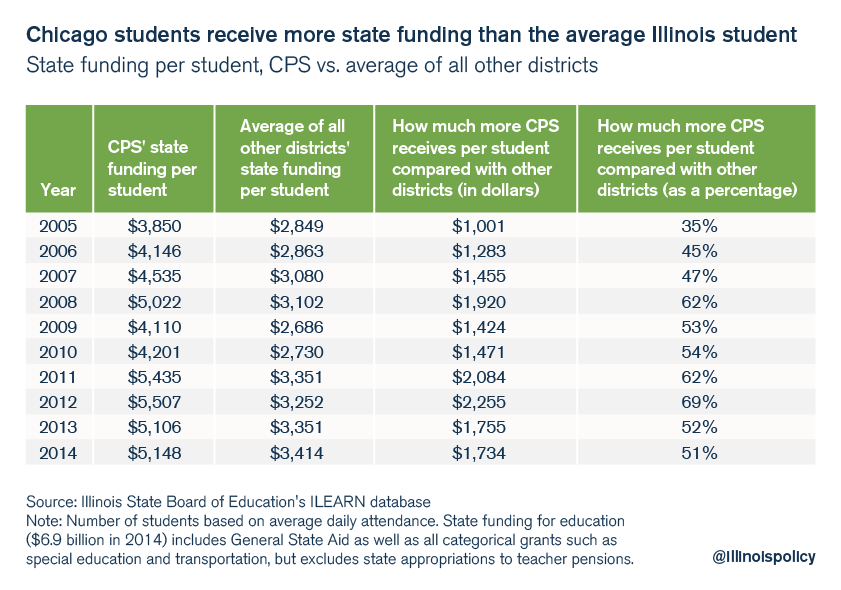

More than a quarter of the state’s $6.96 billion education budget distributed via state funding formulas is paid out through the state’s Poverty Grant. These grants are allocated based not only on the number of low-income students in each district, but also on the share of each district’s student population that is low-income. The larger the share of low-income students a district has, the more per-student funding a district receives.

CPS, whose student population is 92 percent low income, benefits heavily from the Poverty Grant. In fact, CPS receives more per-student funding for low-income students than 95 percent of the school districts in Illinois.

CPS received $2,571 per student in Poverty Grants in 2014, nearly the maximum amount any district can receive.

Only 38 of the 859 total districts across the state receive more funding per low-income student than CPS. Those districts include cities such as East St. Louis, Chicago Heights and Harvey – cities with student populations that are deemed 100 percent low-income.

In percentage terms, Chicago receives 43 percent of the entire $1.9 billion Poverty Grant funding even though it only has 30 percent of the state’s low-income students. The rest of Illinois’ school districts are left with little more than half of all Poverty Grant funding, even though those districts have nearly 7 in 10 of the state’s low-income kids.

Myth No. 3: When state pension contributions are included, CPS kids are left with less than their fair share of state funding. According to Claypool, “No teacher I know wants to make a choice between funding their classrooms or their retirement. Unfortunately, this is the choice our state’s broken system has forced CPS to make.”

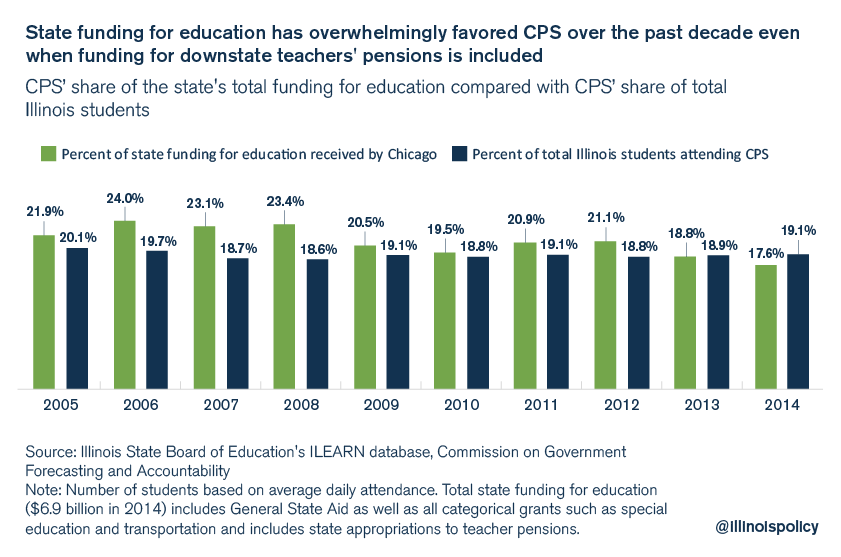

Fact: Over the past decade, the state has consistently given CPS more than its fair share of funding – even when state pension contributions are taken into account.

Even when state teacher pension contributions for districts outside of Chicago are taken into account, CPS has consistently received a disproportionate share of total state funding. Though CPS’ student count has remained around 19 percent of total state student attendance for the last decade, CPS has frequently received more than 20 percent of total state funding for education.

Only in the past year, as state contributions to the downstate teachers’ pension fund have grown dramatically, has Chicago’s share of funding fallen measurably below its share of state student attendance.

Overall, the state has proportionally spent more dollars on CPS students than on students in other districts. At the peak in 2008, CPS received $1,239 more state dollars for each of its students than other districts received for theirs.

On average during that decade, a CPS student received $483 more state dollars a year than his or her peer in another district, even when pensions were added in.

In all, over the past decade, CPS received more than $1.4 billion in additional state funding when compared with a system in which state funding is granted in proportion to a district’s share of the statewide student population (i.e., Claypool’s “20-20 funding” plan).

Myth No. 4: State funding for CPS has declined over the past five years. According to Claypool, “On average, school districts across our state have seen a 40 percent increase in total state education funding over the past seven years. How about Chicago? We’ve suffered a 10 percent reduction.”

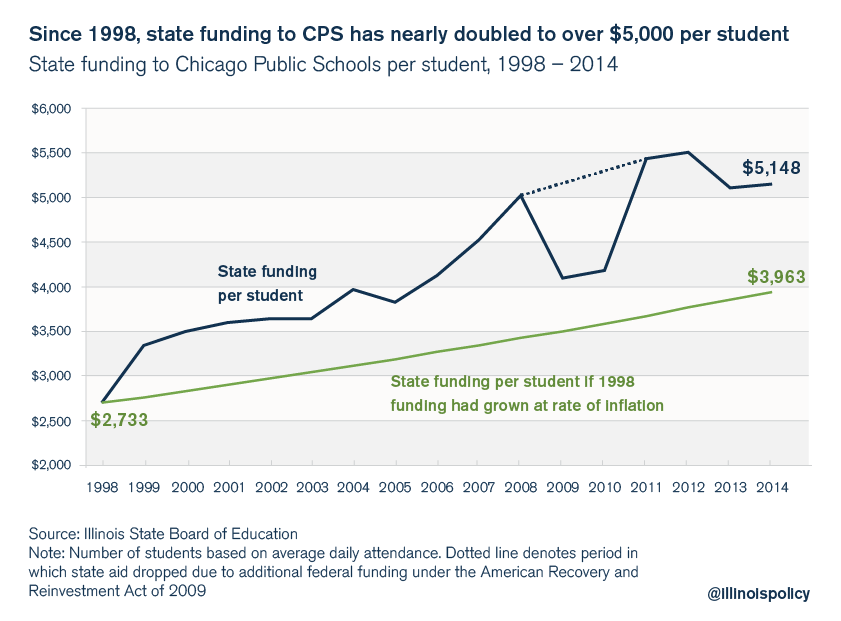

Fact: State education funding for CPS has nearly doubled over the past 15 years.

Claypool’s claim that state spending on Chicago schools has been declining since 2009 paints a false picture of how much state funding has been going to Chicago students. While state funding per student has declined slightly from its peak in 2012, overall state appropriations to CPS have grown significantly over the last decade and a half.

State funding to CPS has grown by over 1.5 times the rate of inflation since 1998. In 2014, a CPS student got $2,400 more in state money than that student would have received in 1998, an 88 percent increase.

In addition, Claypool continues to ignore the fact that both state and local taxpayers have given more than enough to CPS to properly fund Chicago student educations. CPS’ total annual revenues, including federal, state and local funds, have increased to more than $15,000 per student in 2014 from just over $8,000 in 1998.

Claypool’s misguided 20-20 funding idea

Claypool’s claims about how the state’s education funding formulas discriminate against Chicago are baseless. In fact, CPS has actually benefited greatly from the state’s education appropriations.

But there is more wrong with Claypool’s claims than just his math. His demand – that the state give CPS funding that’s proportional to the district’s share of the statewide student population – is also misguided.

The GSA’s current funding formula is designed to grant more state education dollars to poor districts that don’t have the local funding necessary to educate students on their own. This additional state funding overwhelmingly finds its way to poorer districts.

If the state were to grant funding based on Claypool’s 20-20 idea – that Chicago receive state funding equal to its share of the state’s total student population – then the wealthiest districts in the state would also receive funding equal to their share of the student population. That would result in an increase in state funding for wealthy districts and would strip Illinois’ poorest districts of core state education funds.

Fixing education funding through pension reform

CPS officials are doing their best to blame the state for the district’s current financial crisis. Claypool blames inadequate state aid as the main reason why the district is faltering and has demanded state bailouts in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

But the truth is CPS’ financial troubles are not due to a lack of state funding. Instead, district officials are responsible for the mishandling of CPS finances – through pension pickups, pension holidays and overgenerous salary increases for teachers.

If CPS wants to return to solid financial footing, a state bailout is not the answer. A bailout wouldn’t only be unfair to other school districts and state taxpayers, it would also allow CPS officials to ignore the necessary reforms needed to structurally fix CPS.

However, state and city officials’ other proposal – to reform the state’s education funding formula – won’t solve the fundamental problems in Illinois education, either.

While there are some reforms to the funding formula that can and must be enacted, none of them will matter as long as pensions keep crowding out state funding for classrooms.

2014 revealed the extent of the pension problem when the state contributed hundreds of millions of extra dollars to downstate teachers’ pensions. That was the first year that Chicago’s share of state funding fell measurably below its share of state student attendance. However, while Chicago received fewer classroom dollars as a percent of total state education spending, so did every other district in Illinois.

Pensions are wreaking havoc on state funding for classrooms. Fifty percent of all state education dollars now go toward teachers’ retirement costs. That’s eating into state spending that should go into the funding formula, the Poverty Grant program and other categorical grants such as special education.

That’s bad news for CPS, which is actually a winner when it comes to the state’s funding formulas. As long as more and more state education dollars are appropriated to downstate teacher pensions instead of the education funding formulas, Chicago, and every other school district, loses out on additional state funding.

If Claypool and other CPS officials really want more education funding from the state, their focus should be on promoting comprehensive pension reform at both the Chicago and state levels.

Fortunately, there are several pension reforms that Claypool and others can demand that would ease the pension crisis and send more state education dollars flowing to Chicago. For starters, Illinois can move new downstate and Chicago teachers into 401(k)-style plans, grant existing teachers the option to opt in to self-managed retirement accounts and end the practice of teacher pension pickups statewide.

In addition, lawmakers can better align state education spending going forward by enacting the following reforms:

- Eliminate the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law and Tax Increment Financing subsidies from the state’s education funding formula

- Stop offering education block grants to CPS for special education, transportation, etc.

- Require downstate districts to pay for the annual pension costs of their retired teachers

- End teacher pension pickups by banning the practice statewide

- The state and CPS should begin steadily paying down their enormous pension debts

Enacting these reforms will go a long way toward fixing the state’s education funding problems and the pension crisis.