The case for updating Illinois’ felony-theft laws

To make Illinois smarter on crime and save taxpayer dollars, theft laws must be kept up to date

Illinois’ prison population has tripled since 1978 for many reasons: growth in prison admissions, reduced sentencing credit, increased length of prison sentences and a high rate of recidivism.

Achieving Gov. Bruce Rauner’s goal of reducing Illinois’ prison population by 25 percent by 2025 and reining in prison costs will require structural reforms to Illinois’ criminal-justice system.

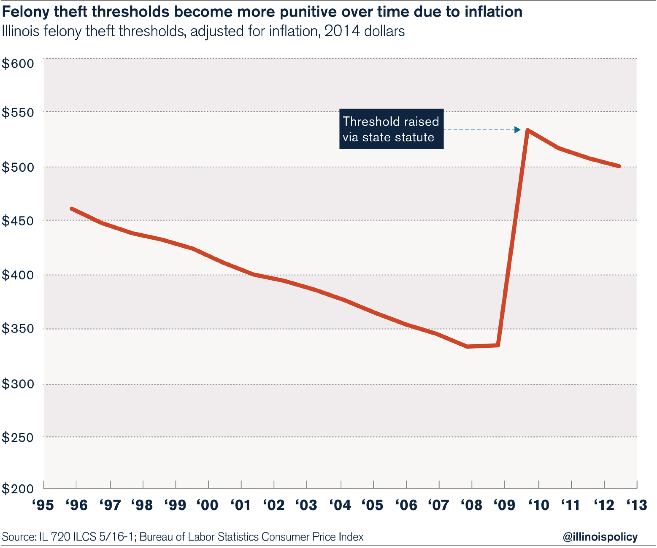

Updating felony-theft laws to ensure criminal penalties don’t become more punitive merely due to inflation is one commonsense reform that the state could institute.

For example, if someone was arrested for stealing a watch worth $250 in 1982, that person could have been charged with a Class A misdemeanor, and if convicted, could have spent up to a year in jail. Today, that same watch would be worth $618, and stealing it would be a Class 3 felony, punishable by two to five years in prison.

In Illinois, theft becomes a felony when the value of goods stolen is $500 or higher. In most states across the country, however, theft becomes a felony when the value of goods stolen is $1,000 or higher.

Because lawmakers have not regularly and sufficiently updated the relevant statutory provisions, Illinois’ felony-theft laws have become more punitive than originally intended by the General Assembly. Inflation causes this: As the value of money depreciates, the value of goods a person must steal in order to be classified as a felon continually drops. As a result, low-level offenders who might deserve misdemeanor convictions for their offenses get felony charges instead, increasing the cost of Illinois’ already overburdened prison system.

Of course, anyone who commits a property crime must be punished. But what is the most cost-effective way to punish these offenders? Parole or up to one year in jail makes more sense for low-level offenders than felony-level sentences, which cost Illinois over $38,000 per inmate a year.

Relying too much on prison sentences can also undermine justice for crime victims. An offender in prison isn’t working to reimburse his or her victim for the value of the stolen property. Instead, the victims pay, through tax dollars, to support the people who have wronged them. Restorative-justice programs, on the other hand, have been shown to improve victim satisfaction and save taxpayer dollars because they ensure property offenders work to pay back their victims – something that doesn’t happen when the wrongdoers are behind bars.

Updating theft penalties hasn’t led to an increase in crime in other states. Twelve states that raised their felony-theft thresholds to $1,000 or even higher saw declines in thefts. In Texas, for example, where the threshold was raised to $1,500 from $750 in 1993, thefts fell by 80,000 – even as the state added over 8 million new residents. And as of Sept. 1, Texas raised the felony-theft threshold again, to $2,500.

Keeping laws up-to-date is critical to saving taxpayer dollars and improving the effectiveness of Illinois’ criminal-justice system. Updating the state’s theft statute is one small step to take to make Illinois smarter on crime.