Act locally: Right-to-Work zones can spark IL comeback

For Illinois’ downstate communities that have felt the pain of out-migration and need to revitalize their industrial base, a local Right-to-Work ordinance can be their first step to a comeback.

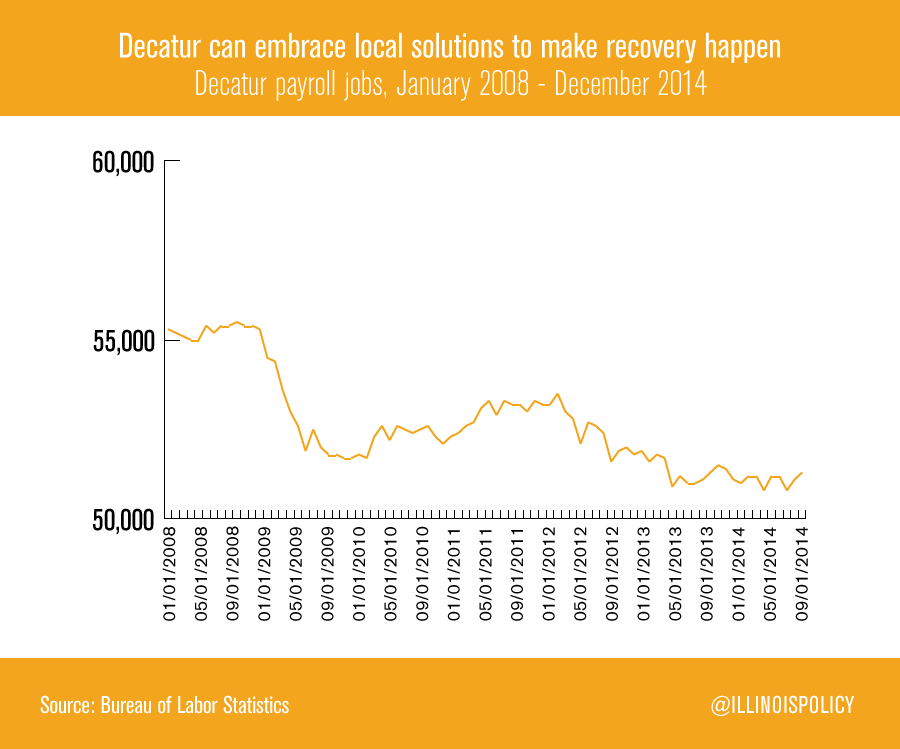

In his statements before a Decatur audience, Gov. Bruce Rauner highlighted the opportunity for local governments in Illinois to become “employee-empowerment zones” by adopting local regulations that promote job creation. Workers in these areas would be allowed to choose whether or not to join a union, an option they don’t currently enjoy.

Given there is no statewide legislation preventing localities from enacting Right-to-Work ordinances, county or municipal governments can pass an ordinance that protects workers from being forced to join a union or pay union dues as a condition of getting a job. Illinois’ local governments have especially strong muscles to flex on this issue, given the extraordinary “home rule” powers they are granted under the state constitution.

The local Right-to-Work movement kicked off in Kentucky, where five counties have already passed countywide Right-to-Work ordinances, with more counties on the way. Harry Berry, judge-executive of Hardin County said, “We think it will help economic growth and promote commerce in our community.” The Kentucky model provides a framework for Illinois localities to make the same reforms.

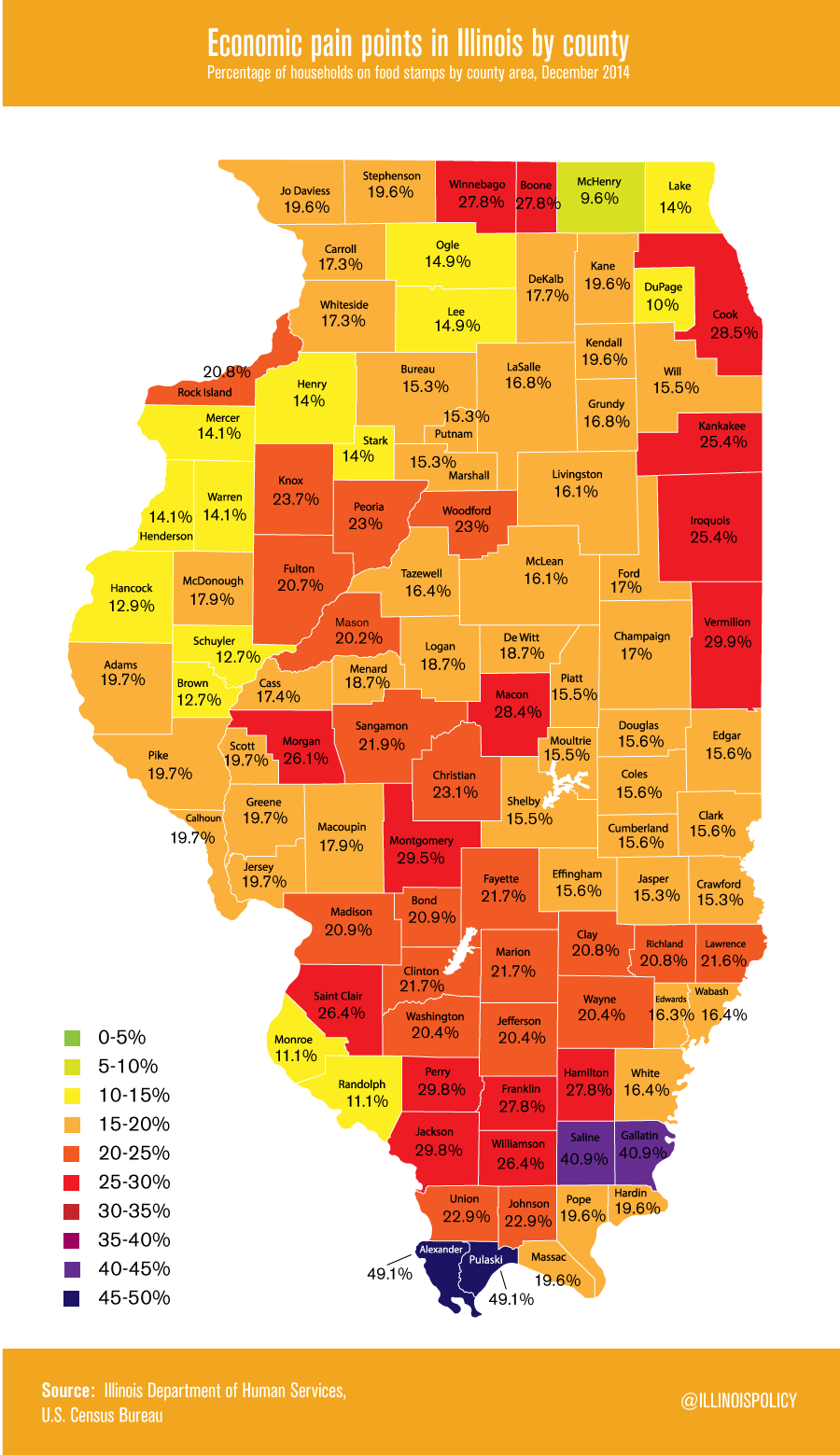

Such reform is one solution for Illinois communities that have been economically devastated by the out-migration of businesses and workers, and who have seen their tax base eroded as a result. Illinois’ dependency crisis also highlights the need for local solutions in communities that want to attract businesses. In a number of work-starved counties, more than a quarter of all households are dependent on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, commonly known as food stamps.

In addition, counties along Illinois’ borders, especially the border with Indiana, are vulnerable to losing businesses that can hop the border. Former Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels has highlighted the importance of Right-to-Work legislation, saying “A lot of companies that don’t really want to talk about it publicly are perfectly explicit about talking about it in private.” Daniels added that before Indiana became a Right-to-Work state, “almost the only time we would ever lose a competition for new jobs it was to a Right-to-Work [state].”

For Illinois’ downstate communities that have felt the pain of out-migration and need to revitalize their industrial base, a local Right-to-Work ordinance can be their first step to a comeback.

Rauner’s Decatur audience was more than familiar with the need to create opportunity. Decatur’s industrial base has suffered under statewide policies that make Illinois uncompetitive, and have left the city unable to recover the jobs it lost during the recession. In addition, 28.4 percent of Macon County households depend on food stamps, more evidence of Decatur’s need to embrace pro-opportunity policies.

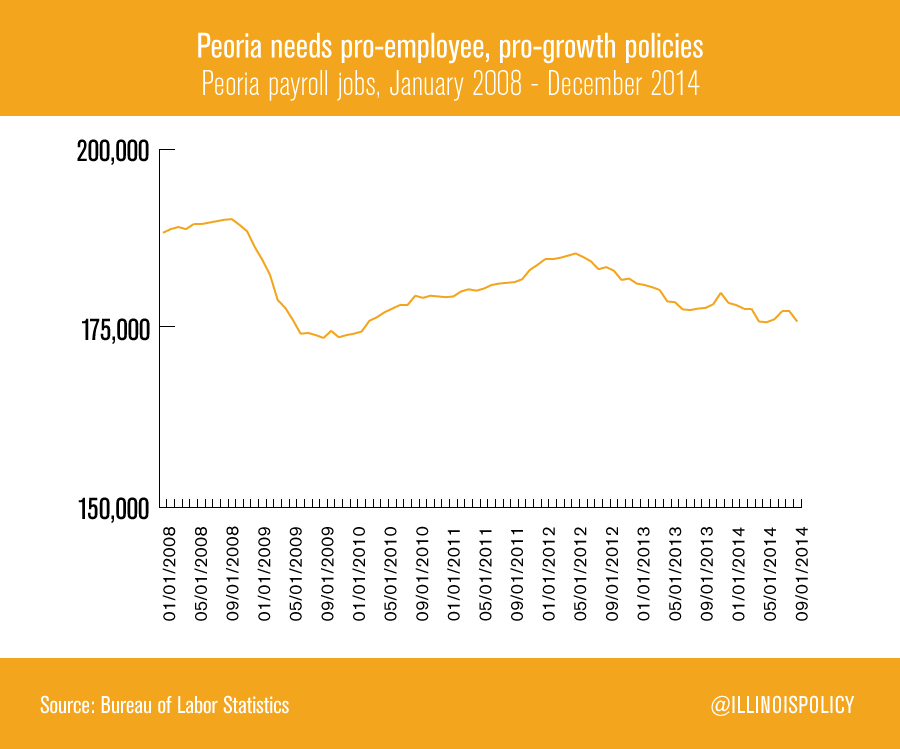

Peoria, Illinois, is another industrial powerhouse and is home to Caterpillar Inc., the state’s largest employer. However, regulatory and tax issues, such as workers’ compensation and forced unionization, have made Illinois uncompetitive with states like Indiana, which is a much more attractive location for Caterpillar to expand its manufacturing base. Peoria could use a Right-to-Work ordinance to encourage Caterpillar to create more jobs locally, and to kick-start a local jobs recovery that is slow in coming and still trending down.

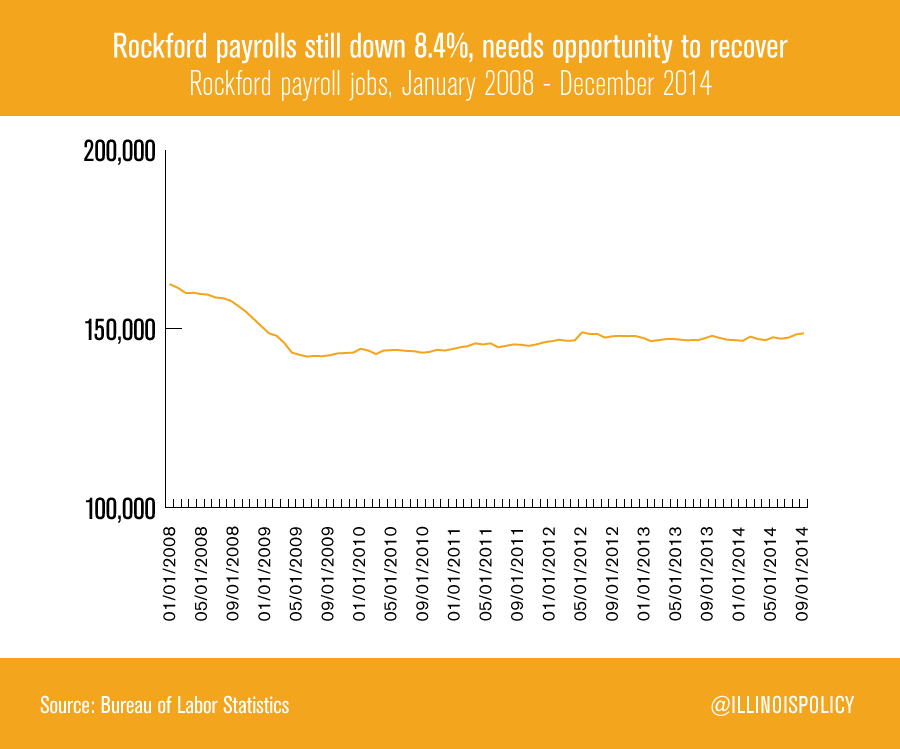

Rockford, Illinois, experienced a steep decline in jobs over the recession era from which the community has not recovered, combined with an alarming 27.8 percent of households on food stamps. Rockford also has to contend with nearby Wisconsin when it tries to attract and keep businesses. The city’s economy would be made much more competitive should Rockford choose to become a Right-to-Work zone.

The story of economic hardship is repeated across the state in communities large and small. With economic reform being held up for decades in the General Assembly, local communities should be ready to take matters into their own hands. Illinois’ comeback is going to take time, but it need not wait for a General Assembly unwilling to embrace pro-opportunity policies. Local areas can kick-start their comeback by fostering economic growth and embracing worker choice through the power of Right-to-Work zones.