Union membership decreases nationwide

Last week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its latest report on union membership in the United States, which covers 2013. The results showed that unions failed to gain members – a fact that will likely prove disappointing for union officials, who might have hoped to regain lost membership under a very pro-union president....

Last week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its latest report on union membership in the United States, which covers 2013. The results showed that unions failed to gain members – a fact that will likely prove disappointing for union officials, who might have hoped to regain lost membership under a very pro-union president.

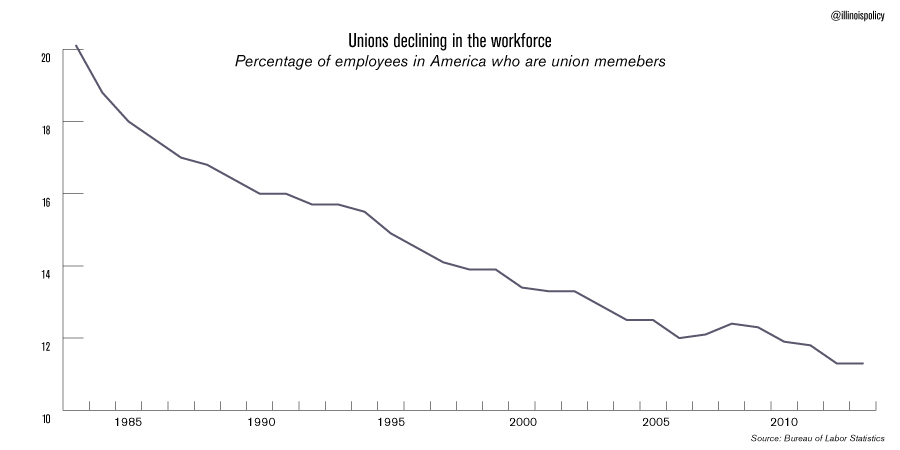

The long-term trend, going back to at least 1983, has been for unions to slowly but steadily lose members. Total union membership was 17.7 million in 1983, but declined to at 14.5 million at the end of 2013.

The decline of organized labor is even starker when expressed in terms of the percentage of the workforce that is made up of union members. Unions have lost members even while the workforce has grown. In 1983, union members made up 20.1 percent of the workforce. In 2013 that number had declined to 11.3 percent.

Organized labor did better in Illinois in 2013, gaining 50,000 members and bumping its percentage of the workforce up from 14.6 to 15.8. But that was not enough to offset union membership losses in other states, including union strongholds such as California (59,000 members lost) or Pennsylvania (33,000 members lost).

Nationally, the Obama administration has gone to great lengths to cater to unions. His first Secretary of Labor, Hilda Solis, thought of herself as the “humble servant” of organized labor, and did all she could to protect union officials. New financial reporting standards that were under consideration during the Bush administration were rejected, making it more difficult for union critics to monitor union trusts, verify union officials’ compensation, or prevent the theft of union funds. New rules even forced employers to reveal more about the attorneys who advised them on labor laws – a move the American Bar Association itself opposed.

All the efforts of the Obama administration have not been enough to overcome actions taken by a handful of states – Indiana and Michigan passed Right-to-Work laws, while Wisconsin rewrote its government labor law.

But the real problem is that union officials have squandered much of the goodwill that they had built up among the public. Since the 1930s approval ratings for unions have usually been well in the range of 60 percent, and 65 percent of Americans approved of organized labor in the late 1990s. But since then public support of unions has dropped noticeably, with a slim majority of 54 percent now expressing their approval in the 2013 Gallup poll.

The real reason unions are struggling to maintain members isn’t an excess of scrutiny, or even less favorable state laws. The real reason why the public’s opinion of unions has dropped is union officials who are out of touch with the values of the people of Illinois.

For instance, once people understand the story behind the Harris v. Quinn case – in which the Service Employees International Union tried to unionize parents who care for their disabled children – they quickly understand that the union has grossly overstepped its boundaries. Unions exist to protect employees, but people like Pam Harris aren’t employees even if they accept a stipend from a state Medicaid program. But American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees President Henry Bayer was shocked and appalled by parents fighting unionization. In a letter to the Chicago Tribune, Bayer condemned the other side’s “attitude of entitlement.”

In reality, it is Bayer who displayed the attitude of entitlement here – apparently he believes that whenever anyone receives help from the state, he is entitled to a cut of that money.

That sort of mindset, along with the record of workers losing jobs on account of ill-timed strikes and unaffordable union demands, explains why unions are having so much trouble maintaining their numbers. If union officials want to reverse this long-running trend, they should take a hard look in the mirror.