The new AFSCME contract: a deal Illinois can’t afford

Gov. Pat Quinn managed to avoid a government worker strike, but that doesn’t spell success. There is still much that remains unknown about the terms of the tentative agreement that Illinois just reached with Council 31 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, but the main features that are emerging paint a...

Gov. Pat Quinn managed to avoid a government worker strike, but that doesn’t spell success. There is still much that remains unknown about the terms of the tentative agreement that Illinois just reached with Council 31 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, but the main features that are emerging paint a picture of a contract the state can’t afford.

Here’s what Quinn needed to deal with:

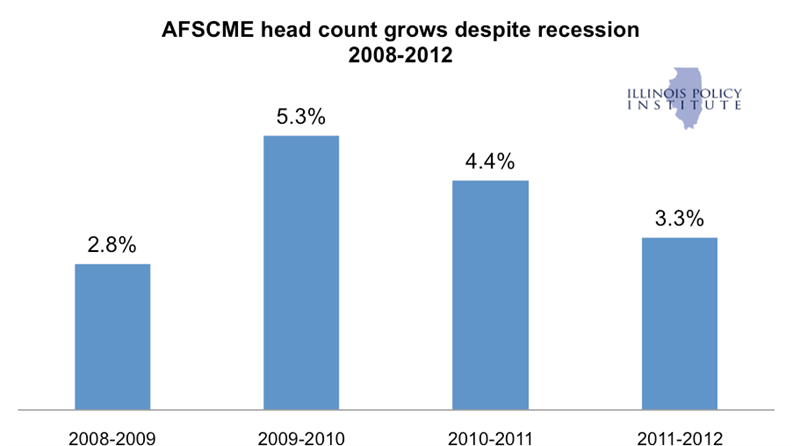

- Between 2008 and 2012 the AFSCME workforce expanded to 38,837 workers, an increase of 17 percent.

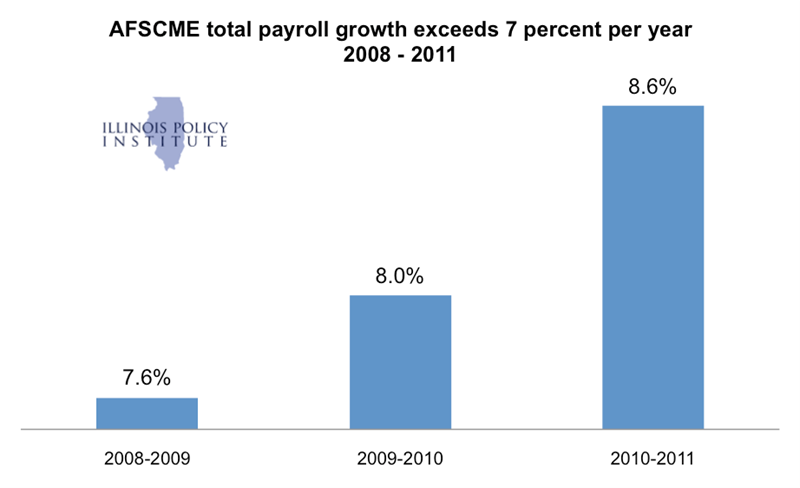

- Between 2008 and 2011, the overall annual cost of wages for these employees shot up by 26 percent, or nearly $500 million.

- At the same time, overall private sector employment slid – in 2012 there were still 220,000 fewer Illinoisans employed than there were in 2008.

Quinn failed to tackle these mounting challenges. For the state to spend so much more on government workers while its economy struggles is lunacy. This may be a hard truth for government workers and their supporters to accept, but the state really needed a contract that right-sized government worker compensation to a level that the public could afford, or at the very least held them steady and gave the economy a chance to recover.

Instead the governor agreed to reinstate an across-the-board increase, originally scheduled for 2012. Quinn originally said Illinois could not afford these. If the state couldn’t afford them then it certainly can’t afford them now. Quinn also agreed to further across-the-board pay increases of 1.5 to 2 percent for 2014 and 2015.

But that’s only the beginning. These pay increases will be on top of automatic “step” increases that state employees receive every year. Depending on job classification and seniority level, these step increases range from 2.7 to 5.5 percent per year. These are hidden raises that are seldom mentioned in news accounts of collective bargaining, but they have a definite effect on the cost of state government.

At the start of negotiations Quinn supposedly wanted to freeze the steps and even move employees down a step or two – in effect cutting wages. But collective bargaining is done in secret, so taxpayers can’t know for sure. But if AFSCME officials are to be believed, Quinn was still pushing for a hard freeze up until last week – no raises, no steps.

What happened to change the governor’s mind? The union apparently will allow Quinn to charge retired state employees for part of the cost of their health insurance. (Free retiree health insurance, which state government retirees have had up to now, is almost unheard of in the private sector.) Under state law this is a change that the governor should have been able to make on his own, but AFSCME was in a position to punish the governor if he did by making outrageous wage demands on pain of strike. Which is essentially what they did, one suspects; the pay raises were very likely ransom that the governor paid to get control over retiree health insurance costs.

Having retirees contribute to the cost of their health insurance could save the state more than $400 million dollars per year, a respectable sum; but we don’t know what the governor will be able to do without provoking AFSCME’s wrath, or if the governor will make the most of it. Even with the most optimistic assumptions this will not provide enough savings relief. Illinois is behind by more than $9 billion on payments to vendors and in a more than $200 billion hole in terms of unfunded pension liabilities. Further savings, not tradeoffs, were in order.

The state needed bold leadership and a new contract that brought state employee compensation in line with what the state can afford. Instead it got a contract with pay raises that will inevitably drive up the cost of government. (That includes higher pension costs, since pensions are based on wages.) The contract will increase the pressure for tax hikes in what is already a heavily taxed state.

One can argue about whether the problem was a politically weakened governor or a dysfunctional state bargaining law that gave AFSCME the power to shut down state government. But at least one of the two failed, and Illinoisans will pay the price for that failure.