8 things to know about Chicago’s pension-reform law

A Cook County judge is scheduled to rule on the constitutionality of Chicago's pension-reform law on July 24. No matter what the outcome is, the pension overhaul will eventually end up in the Illinois Supreme Court. But the ruling may give a clue as to whether or not the city’s reforms will ultimately be upheld.

Chicago is facing billions in pension debt that threatens to bring city government to its knees. Chicago households are each stuck with $33,500 in pension shortfalls from the four city-run pension systems and other overlapping governments, including Cook County, which add up to more than $34 billion. The city’s budget is under tremendous strain from deficits of up to $1 billion next year – due in large part to a huge increase in required police and fire pension payments.

Chicago’s ability to pay down its pension debt is in a precarious situation, as a Cook County judge is scheduled to rule July 24 on the constitutionality of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s 2014 pension-reform overhaul for municipal workers and laborers’, which was signed into law by former Gov. Pat Quinn.

The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, the Municipal Employees Society of Chicago and other groups challenged the law after its passage, and it has been stuck in the courts ever since.

No matter what the Cook County judge decides, the mayor’s pension-reform law will eventually end up in the Illinois Supreme Court. But the ruling may give a clue as to whether or not the city’s reforms will ultimately be upheld.

The Illinois Supreme Court has already struck down the state’s own reform effort, Senate Bill 1, declaring that pension benefits cannot be “diminished or impaired,” which sets the precedent that Chicago’s pension-reform law will not stand.

However, Emanuel has constantly argued that his reform effort is different and will ultimately be found constitutional.

Here are eight important details of Chicago’s pension-reform law:

1. It affects only half of the city’s workers

The law applies to city employees who are members of the municipal and laborers’ pension funds. The city’s fire and police pension systems, as well as the sister-government pension systems that include teachers, park and transit workers, are not included.

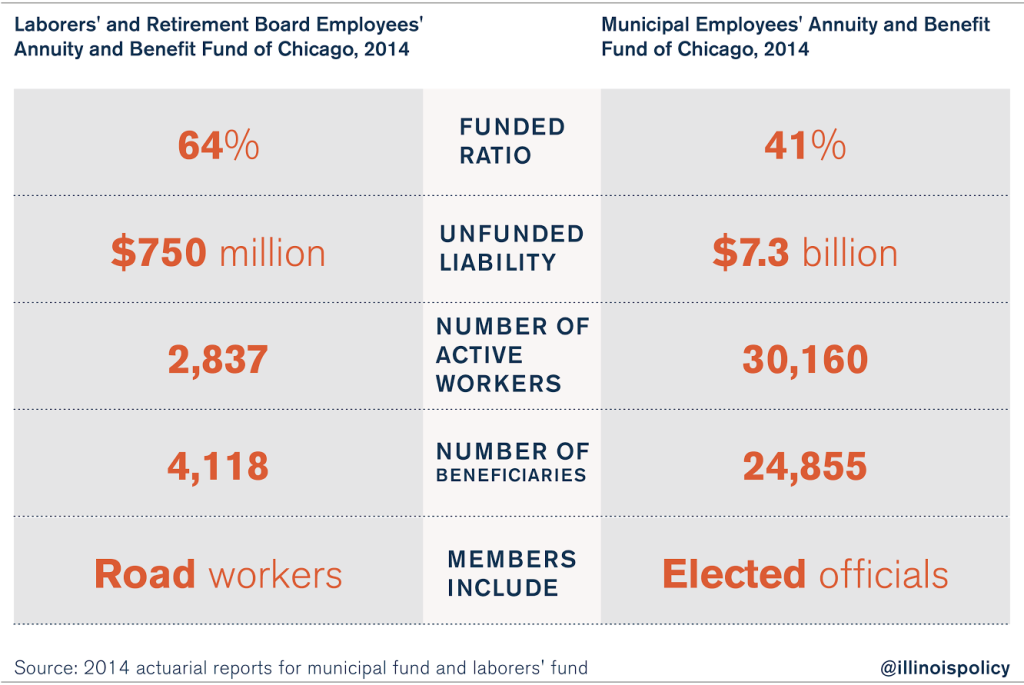

In all, Chicagoans are on the hook for more than $34 billion in unfunded pension liabilities, of which only $8.3 billion come from the municipal and laborers’ systems.

2. It increases employee contributions to their pensions

Under the terms of the law, employee contributions to the pension funds would grow incrementally to 11 percent by 2019 from 8.5 percent today.

3. Employee cost-of-living adjustments, or COLAs, go down

The law freezes retiree COLA benefits in 2017, 2019 and 2025. The bill also alters the COLA calculation to the lesser of 3 percent or half of inflation, noncompounded. Currently, municipal and laborers’ COLAs are automatically compounded at 3 percent.

4. Retirement age for Tier 2 workers drops to 65

Rather than increasing retirement ages for Tier 1 employees, workers enrolled in the less generous Tier 2 pension system have the age at which they are allowed to retire lowered to 65 from 67.

5. Establishes a pension-funding guarantee

The law requires the city to pay its annually required pension contributions to the municipal and laborers’ funds. If the city does not contribute the full amount, the pension systems can demand the payment in court, and the city’s share of state grants may be garnished by the systems. In 2016, one-third of state grants may be garnished, in 2017 two-thirds, and in 2018 and ever year after all state grants may be garnished.

6. Extends the amortization periods of the fund’s pension debt

Under the law, the pension funds’ debt repayment schedule is pushed further into the future by 15 years, to 2055 from 2040.

7. Increases city contributions in the form of a ramped payment schedule

The law calls for the city to increase its annual contributions to the municipal and laborers’ pension fund between 2016 and 2020. In 2021, the city will begin paying its Annually Required Contribution, or ARC, to the pension fund. In that year, the city’s annual contribution will be an estimated $450 million higher than it would have been under current law. By 2025, the difference will grow to an estimated $530 million.

8. Chicagoans are facing hundreds of millions of dollars in tax increases

The original pension bill called for a $750 million property tax hike over five years on Chicagoans to pay for increased contributions to the municipal and laborers’ pension systems. However, that language was dropped from the final bill due to objections from the General Assembly and Quinn.

Even though the language mandating a property-tax increase no longer exists, the law still says the city can use other current taxes and revenues to make payments: “The city’s required annual contribution to the fund may be paid with any available funds and shall be paid by the city to the city treasurer.”

That means Chicagoans are still on the hook for hundreds of millions in eventual tax increases needed to pay for the city’s increased contributions to the pension systems.

What could happen?

The courts’ ruling on this law is important because the result will impact other potential reforms in Chicago and in Cook County, which has $5.3 billion in unfunded pension liabilities of its own.

If upheld, Chicago, Chicago Public Schools, and other sister-governments will have a model by which to apply other tax-heavy, reform-lite laws to their other struggling pension systems.

If the Illinois Supreme Court does end up striking down the laws, Chicago and other governments will be back at square one as to a model for pension reform. And Chicago will be on the hook for larger and larger contributions to the municipal and laborers’ pensions in the coming years – that’s on top of the coming police and fire contributions that have already thrown the city into crisis.

Financial institutions have already demonstrated their deep concerns about Chicago’s financial future. Moody’s Investors Service has downgraded the city four times since 2013, knocking it down seven spots to junk status. As things get worse, Chicagoans can expect to see the city and its sister governments’ credit ratings crumble even further.

The city may be able to muddle through in the short term with more borrowing, increased taxes and service cuts, but without real reforms, all of Chicago’s broken pension systems are headed toward insolvency.

The end result will be suffocatingly high property tax hikes to pay for pensions, and more residents than ever fleeing Chicago for the suburbs or greener pastures in other states altogether.