5 ways Illinois can learn from Colorado’s ‘blue state’ literacy reforms

Colorado lawmakers passed an act in 2012 to focus on early literacy development and the science of reading. Its fourth graders are now in the Top 5 states for reading proficiency. Illinois can benefit from adopting five of their tactics.

States such as Florida and Mississippi reversed their poor literacy ratings with legislation aimed at the science of reading, but what can blue states more closely aligned with Illinois’ political atmosphere offer to fix its low literacy rates?

Colorado provides a perfect case study. Both Illinois and Colorado have traditionally Democratic political landscapes. Both give most of the governing of public schools to local school boards.

In July 2023, Illinois lawmakers amended the school code and directed the state school board to support literacy efforts. But more is needed to improve grade-level literacy in Illinois public schools, and Colorado can offer Illinois lawmakers an example for how to push statewide “science of reading” reform in a local-control state.

Colorado’s fourth graders had the fifth-highest reading proficiency rate on the Nation’s Report Card in 2022 with 38%. Illinois ranked 16th and, even worse, it is one of 35 states and the District of Columbia in which just 1 in 3 or fewer fourth-grade students met reading standards in 2022.

Colorado parents can thank lawmakers in part for their state’s high-ranking fourth grade reading proficiency rate. In 2012, Colorado state lawmakers unanimously passed the Reading to Ensure Academic Development Act, which focuses on “science of reading” literacy development for the state’s elementary students.

The term “science of reading” references evidence-based literacy policies. It denotes “the vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing,” according to The Reading League. More simply, it is research about how to most effectively teach reading and comprehension.

Colorado’s act sought to improve early literacy and includes the following five policies for kindergarten through 3rd grade students:

• Rooting reading instruction in the science of reading.

• Assessing for reading deficiencies.

• Creating a reading intervention plan for students identified with a significant reading deficiency.

• Engaging parents with the implementation of their student’s reading intervention plan.

• Collaborating with parents to decide whether students should be promoted to the next grade.

There is much for Illinois lawmakers to learn from Colorado’s literacy tactics and how to implement literacy reform to improve student achievement.

The solutions: Five policies for literacy reform from Colorado

Here’s a look at a five of the policies implemented by Colorado legislators that contributed to their fourth graders ranking among the top of states for reading proficiency.

1. Early literacy instruction rooted in “science of reading”

The Colorado act focuses on providing stu

dents in kindergarten through third grade with the necessary instruction and services needed to ensure students can progress through each grade level and develop necessary reading skills.

Special attention is given to students’ learning in the early years of schooling because research shows a student’s likelihood to graduate high school can be predicted with reasonable accuracy by their reading skill at the end of third grade. By the beginning of fourth grade, students transition from learning to read to reading to learn.

“Students who do not ‘learn to read’ during the first three years of school experience enormous difficulty when they are subsequently asked to ‘read to learn,’” according to the National Center to Improve the Tools of Educators. If a student struggles to read at grade level by the end of third grade, up to half of the printed fourth-grade curriculum is incomprehensible.

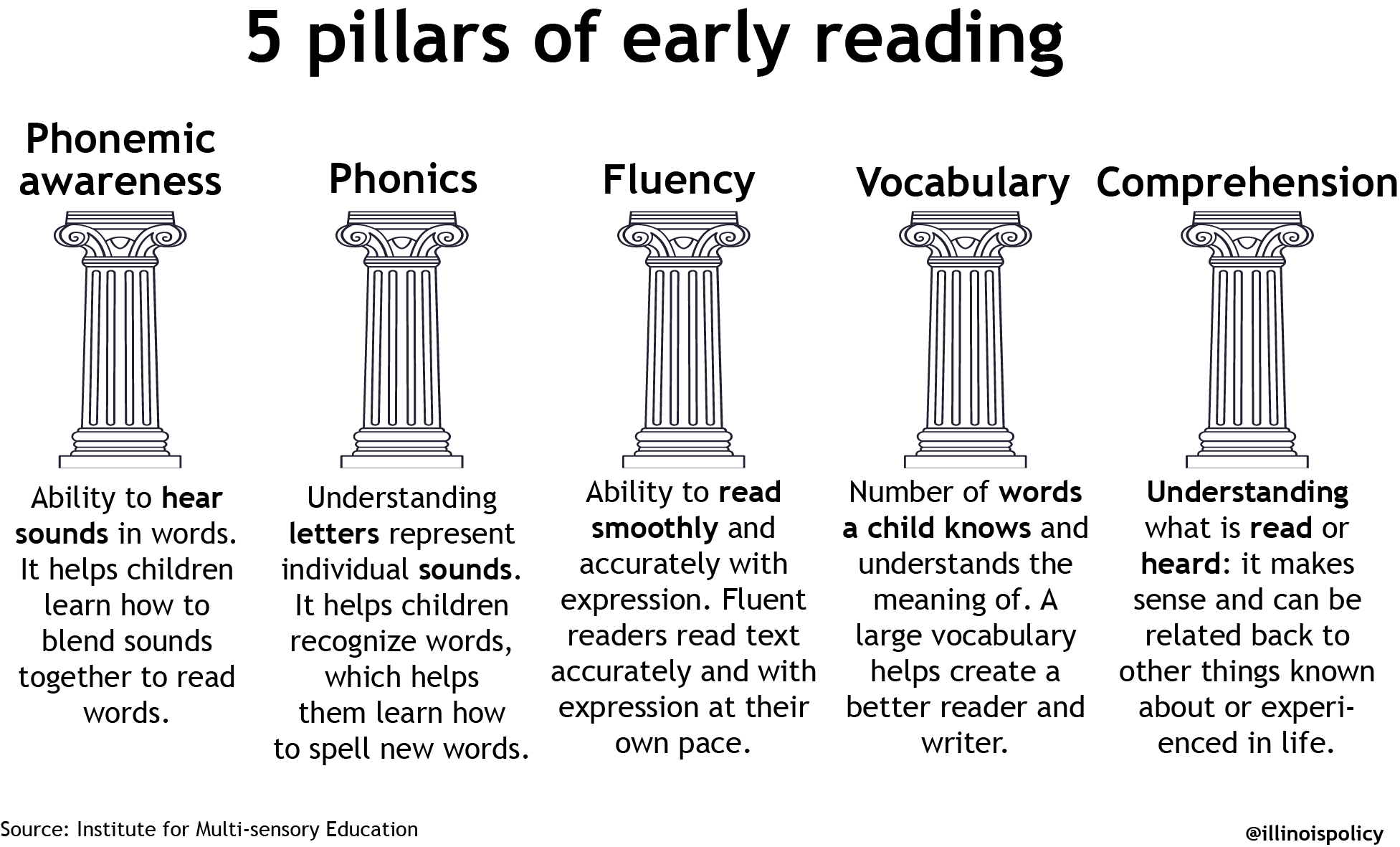

To accomplish reading competency among Colorado’s early learners, lawmakers outlined specifically the foundations of reading instruction for students in K-3. The act specifies the instructional programming and services for teaching students to read must be “evidence based and scientifically based“ with a focus on the five foundational components of reading as identified by the National Reading Panel in 2000: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary development, fluency and comprehension.

2. Assessments to identify reading deficiencies in K-3 students

The Reading to Ensure Academic Development Act requires schools to determine whether kindergarten through third grade students display a “significant reading deficiency.”

Schools are required to assess the literacy development of every Colorado student in kindergarten through third grade and identify any potential “significant reading deficiency” using a universal screening assessment administered to all students. A significant reading deficiency means a student “does not meet the minimum skill levels for reading competency in the areas of phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary development, reading fluency, including oral skills, and reading comprehension established by the state board for the student’s grade level.”

Teachers must administer a reading assessment within the first 90 days of the school year and throughout the school year for students in K-3. Students who display grade-level reading competency on an approved reading assessment do not need to take additional reading assessments for the remainder of that school year, despite the assessments being administered to students three times throughout the school year.

Students who display a possible significant reading deficiency on an approved reading assessment must be given at least one approved diagnostic assessment within 60 days of the interim reading assessment to determine the student’s specific struggle with reading skills.

The Colorado Department of Education is required to create a list of approved assessments which local school boards may choose from to meet the act’s requirement to assess the literacy development of K-3 students. Local school districts are given autonomy to choose from the approved list of interim assessments and diagnostic assessments. The department of education reviews the assessments every four years for approval according to the act.

According to the act, interim assessments must be “scientifically based“ and effectively measure students’ skills in the five foundational components of reading as identified by the National Reading Panel in 2000: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency and comprehension.

3. Interventions, called READ plans, for students identified with a reading deficiency

An individualized “Reading to Ensure Academic Development” plan must be created for any student in kindergarten through third grade who is identified with a reading deficiency through the state’s required literacy assessment. The plan should be developed as soon as a student is identified as having a reading deficiency.

The student’s teacher must develop the individualized plan in collaboration with the student’s parent, if possible. Teachers are required to review each student’s plan at least once per school year to update or revise the plan as necessary to best ensure the student meets reading competency requirements.

The plan must include information about at least these seven components, according to the act:

- The specific, diagnosed reading skill in which the student is deficient and must fix to meet reading competency requirements.

- The goals and benchmarks for the student’s growth towards reading competency.

- The additional reading instructional services and interventions the student will receive including at least a daily literacy block.

- The “scientifically based” reading instructional programming the teacher will use which will address, at a minimum, the five foundational reading components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary development, reading fluency and oral skills, and reading comprehension.

- The way the teacher will monitor and evaluate the student’s reading progress.

- The strategies, aligned with the five foundational components of reading, parents are encouraged to use to help their student achieve reading competency.

- The additional services, if any, the teacher deems appropriate to accelerate the student’s reading skill development.

If a student continues to display a significant reading deficiency for another school year after receiving intervention through an individualized plan, the student’s local school district must ensure the student’s teacher revises the plan to include additional, more rigorous interventions, including more time each day in school for reading instruction. The board must also ensure the student’s principal oversees the student’s other subjects support and assist with providing reading instruction. Finally, if possible, the board should provide the student with reading instruction from a teacher who is effective or highly effective on their most recent performance evaluation and has expertise in reading instruction.

School districts must ensure teachers continue to implement and revise a student’s plan until the student demonstrates reading competency, even if reading competency isn’t met until after K-3.

4. Parental involvement in student’s reading interventions

The act is intentional about involving parents in their child’s reading improvement plan and development of reading skills. The act requires teachers to meet with the parent of a student identified with a reading deficiency to discuss their child’s reading difficulties and to jointly create the student’s plan. Teachers must then provide the parent with a copy of the student’s plan. If the teacher is not able to meet with the parent after making documented attempts, the teacher will create the student’s plan and send a written copy of the plan to the parent.

Teachers are also instructed to communicate the following specific information to the parents of a child with a literacy plan:

- Explain to the parent the research showing reading competency by third grade is a critical milestone to accomplish Colorado’s goal for every child to graduate high school with skill levels that adequately prepare them for college or a career.

- Explain to the parent their student’s reading deficiency and how the teacher identified the deficiency.

- Warn the parent their student will be significantly more likely to fall behind in school if they fail to demonstrate reading competency by the end of third grade and will not have the skills to graduate from high school if the reading deficiency continues.

- Inform the parent state law requires the local school district to provide “scientifically based” reading interventions tailored to their child’s specific reading skill deficiencies.

- Inform the parent the student’s literacy plan will include targeted, scientifically based intervention instruction to address and fix the student’s reading skill deficiencies.

- Encourage the parent to work with the teacher to implement their student’s plan and supplement their student’s in-school reading intervention with strategies to use at home to support reading success.

- Inform the parent if their student’s reading deficiency continues to the end of the school year, state law requires the parent and student’s teacher, as well as other school district staff, to meet and discuss whether the student should be retained in their current grade level as an intervention strategy.

The act requires school districts to ensure parents are kept informed by their student’s teacher with regular and ongoing updates about the results of their child’s interventions through their individualized plan and their child’s progress in achieving reading competency.

5. Parental involvement in grade promotion decision for reading deficient students

The literacy act creates collaboration with parents for decision-making about the reading development of students with reading deficiencies. The act requires an end-of-year parent meeting between the teacher and parent of a K-3 student with a reading deficiency to discuss and decide whether their child will advance to the next grade level.

If a K-3 student displays or continues to display a reading deficiency within 45 days of the end of the school year, the teacher or a staff member from the school district must give written notice to the student’s parent informing them of the implications of entering fourth grade with a significant reading deficiency, informing them of the state’s legal requirement for them to meet with their child’s teacher and other district staff to consider grade level retention as an intervention strategy and scheduling a meeting with the parent to discuss potential retention. The notice must also inform parents their child’s teacher and school district staff will decide whether to retain or promote their child if the parent does not attend the scheduled meeting.

The end-of-year parent meeting and written notice is not required for students with certain disabilities, students learning to speak English whose reading deficiency is caused by their language skills and students who have been on a literacy plan and are already completing the second school year at a grade level.

At the end-of-year parent meeting, the teacher and school district staff are required to communicate and discuss the following information with the parent:

- The serious implications of entering fourth grade with a significant reading deficiency and the importance of demonstrating reading competency by the end of third grade.

- State law’s requirement for the parent, teacher and other school district staff member to meet and discuss grade level retention as an intervention strategy.

- The “body of evidence” displaying the student’s reading deficiency, such as the student’s scores on formative and interim assessments and their independent work from classroom assignments.

- The likelihood the student will be able to maintain academic progress at the next grade level.

- The increased level of intervention the student will receive in the next school year regardless of whether the student advances to the next grade level.

- The potential effects on the student if they do not advance to the next grade level.

After discussing that information, the parent, teacher and a staff member from the student’s school district will decide if the student will be promoted to the next grade level or be retained, and a written statement with the decision must be given to the parent and to the school district superintendent. The act gives the ultimate decision to parents on whether their child stays or advances to the next grade level in case of disagreement between the parent, teacher and school district staff member. Individual school boards can decide not to give parents the final decision-making power if they specify that in their school board policy implementing the state literacy act.

Any decision to advance a third-grade student with a significant reading deficiency to fourth grade, even if that decision is made by the student’s parent, must be approved by the school district’s superintendent. If the superintendent doesn’t approve the decision to advance the student, the school district must notify the parent about the superintendent’s decision and basis for the decision through a written statement.

While the act outlines the decision-making process for whether students in K-3 should be promoted or retained, the act doesn’t limit the ability of local school boards to establish policies and procedures deciding a student at any grade level should not advance to the next grade level. That is true for whatever reason is deemed sufficient by the local school board.

Colorado serves as example for how to push statewide literacy reform in a “local control” state

Similar to Illinois and other states, Colorado is a local-control state, which means “the governing and management of public schools is largely conducted by elected or appointed representatives serving on governing bodies, such as school boards or school committees, that are located in the communities served by the school,” according to the Great Schools Partnership’s Glossary of Education Reform.

Colorado’s state constitution requires the legislature to establish and maintain a “thorough and uniform system of free public schools throughout the state.” But it also grants local school boards the authority over instruction in each district’s public schools and prohibits state lawmakers and the state board of education from prescribing which textbooks schools must use.

In accordance with Colorado’s strong local control, the enactment of the literacy act means “much of the work of READ Act implementation and effective literacy instruction is the responsibility of districts,” according to a Stand for Children Colorado report on the act.

While the act is a state law that applies to all public schools in Colorado, each district has the authority to uniquely implement the law, especially when it comes to specific curriculum or instruction selections so long as the reading curriculum and instruction is evidence-based.

Illinois is also a local control state, so local boards of education have control over curriculum and other policy decisions. When Illinois amended the Illinois School Code in July 2023 to outline specific actions the Illinois State Board of Education must undertake to support literacy efforts in school districts, the board left it up to local decision-makers to determine what is best for their districts rather than mandating districts implement the literacy plan or prescribing specific materials or assessments.

Ultimately, Illinois’ legislative amendment did little more than mandate the board of education to offer guidance to Illinois public school districts on literacy improvement tactics. More concrete literacy improvements such as those in Colorado can help Illinois students see significant improvements in literacy while honoring the local control of school districts.

Illinois lawmakers can learn from Colorado’s READ Act and implementation

Other states understand the importance of science-of-reading literacy reform and have enacted such legislation in recent years. Since 2013, 40 states and the District of Columbia have enacted legislation concerning the use of evidence-based methods to teach students how to read, according to Education Week.

Illinois took a step to implement science-based literacy policy by amending the school code in July 2023 to include a section on literacy. It created a comprehensive literacy plan for Illinois which explores evidence-based literacy research. It provided a rubric to evaluate curricula and encourage the implementation of evidence-based reading instruction. It required the state to develop and make available training opportunities for reading teachers that are aligned with the state’s comprehensive literacy plan by 2025.

While it is a positive move, more is needed.

Illinois’ comprehensive literacy plan ought not be lawmakers’ final action in supporting the literacy of the state’s students because it does not actually implement any integral reforms. Illinois lawmakers can learn from Colorado’s literacy efforts and the way lawmakers enacted statewide literacy reform while still giving autonomy to local school boards over many policy decisions.