5 things to know about Illinois’ unsustainable municipal pension fund

Illinois taxpayers are forced – by law – to pay for local-government pensions above all else.

Everyone in Illinois knows that government-run pension debt threatens the state’s fiscal solvency, with debt for state-run pensions totaling more than $100 billion.

But the Illinois fund that manages pensions for local-government workers is often touted as the model for how to run a defined-benefit plan. The Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund, or IMRF, the best-funded pension system in Illinois, has a funding ratio of 87 percent. IMRF covers local-government workers in cities outside of Chicago.

IMRF’s funding level compares favorably to the Chicago police and the Chicago firefighter pension funds, which are only 25 percent funded. IMRF is also better funded than the state’s teachers’ retirement fund, which has just 40 percent of the funds it needs.

There’s a reason the IMRF has higher funding levels than the other government-run pensions. Cities are mandated – through a court-enforced funding guarantee – to fund IMRF pensions before everything else, even if that means cutting budgets for road repair, libraries and police and firefighter pensions.

That wouldn’t be a problem if the cities and their taxpayers could count on making fixed and predictable retirement contributions each year. But they can’t.

City taxpayers are not only responsible for paying the current contributions, but also must make up the system’s pension shortfalls due to poor market returns and the general instability of defined-benefit plans under which retirees receive guaranteed monthly payments when they leave the workforce.

IMRF members, on the other hand, pay a set percentage of their income to the pension system, regardless of any increasing shortfalls or liabilities in the pension plan.

That arrangement – mandated contributions regardless of available city resources – has contributed to fiscal crises across Illinois.

Here are five things about the IMRF that the defenders of the pension fund status quo won’t tell you:

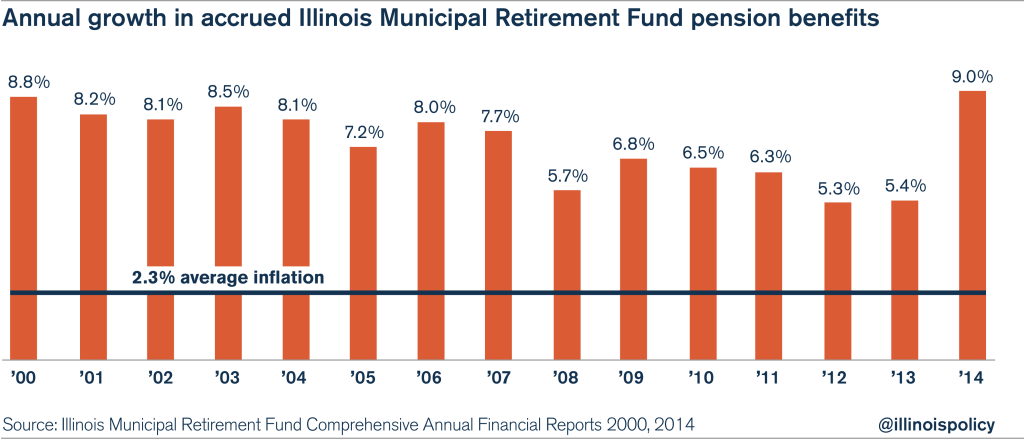

1. IMRF benefits are growing far faster than city budgets and the inflation rate

IMRF accrued pension benefits have been growing at the pace of 7.2 percent a year since 2000, far faster than the 2.3 percent rate of inflation and beyond what city taxpayers can afford.

Since employee contributions for a vast majority of workers are fixed at 4.5 percent a year, this growth in benefits has to be funded by increased contributions from taxpayers.

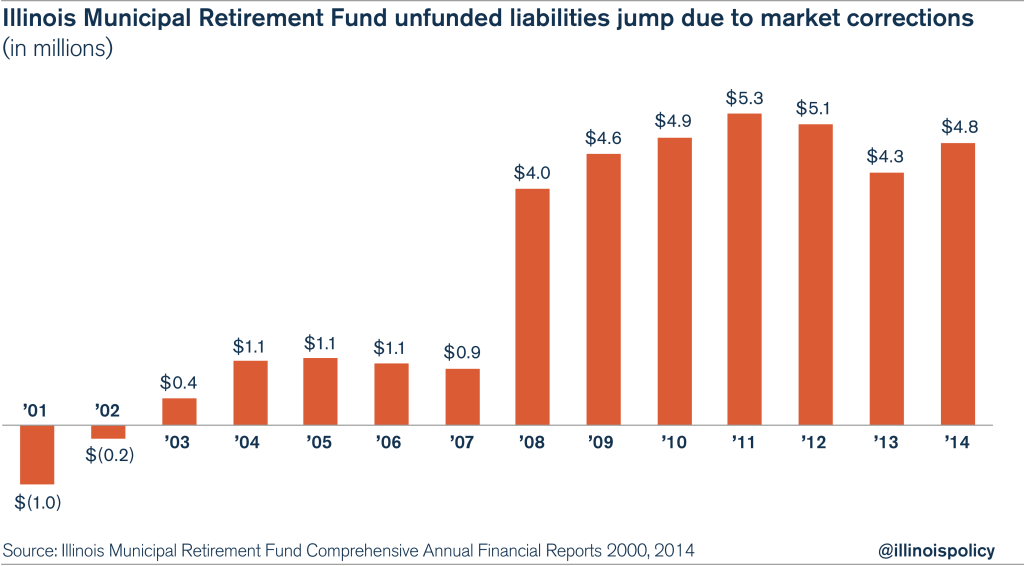

2. An 87 percent funding ratio still means a $4 billion shortfall

In 2000, IMRF actually had a funding surplus. The 2001 market downturn changed that, turning IMRF’s surplus into a shortfall. The 2008 recession made things worse, and the fund’s shortfall had grown to $4.8 billion by 2014.

That pension shortfall will have to be covered through increased funding by taxpayers.

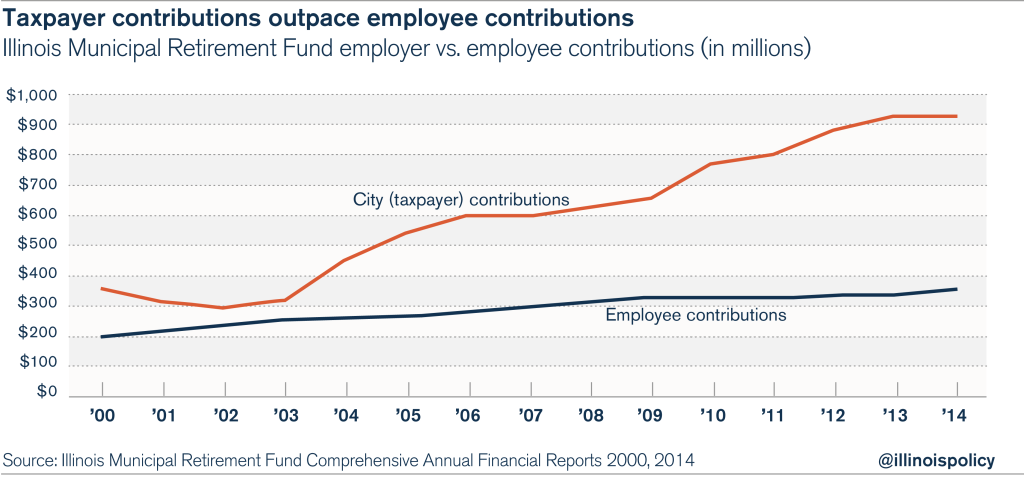

3. Taxpayers are on the hook for increasing city contributions to IMRF to pay for growing benefits and unfunded liabilities

IMRF has demanded more and more money from cities to fund the rapid growth of promised pension benefits as well as to fill the funding gaps left by the 2001 and 2008 stock-market corrections.

Employer contributions to IMRF have grown at the rate of 7 percent a year since 2000, far outpacing local revenue growth and the rate of inflation. Employee contributions, in the meantime, have grown at a slower pace of 4 percent.

Due to this disparity in employer and employee funding obligations, cities contribute far more to the IMRF than the government-worker beneficiaries do. Employers contributed 2.6 times what employees did in 2014, up from 1.8 times in 2000.

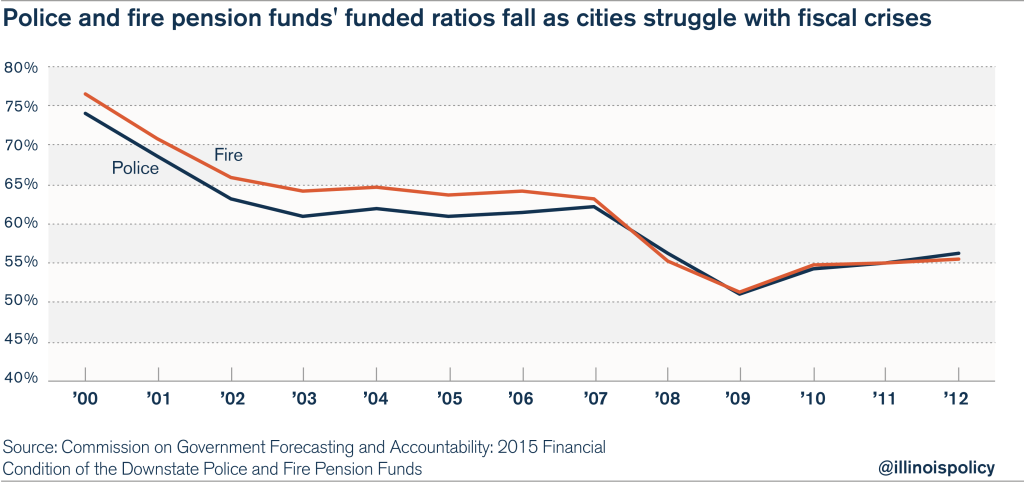

4. IMRF’s funding guarantee pits municipal pensions against local police and firefighter pensions and other services

The rising costs of IMRF liabilities exacerbate the fiscal crises facing hundreds of municipalities across the state.

The money IMRF requires from local employers has to come from somewhere, and cities are increasingly shorting their police and firefighter pension funds, cutting back on local services, and raising taxes and fees to make their IMRF payments.

Downstate police and firefighter pensions are a frequent target of payment cutbacks. Since 2000, the funding levels of police and firefighter pensions have fallen by 20 percentage points. Collectively, the two systems have little more than half the money they need today to pay out future benefits.

Pension costs are consuming more and more of Illinois’ property taxes, which already rank second highest in the country.

The city of Springfield, for example, now dedicates 98 percent of its city property taxes to pay for the pensions of police, firefighters and city workers.

Other cities have raised taxes and fees to combat rising pension costs. Peoria has added new water and natural-gas utility taxes, and also has doubled its garbage-collection fees to help fund its growing pension commitments.

(Chicago, which is not part of the IMRF, is the most infamous example of a city’s raising taxes and fees in order to fund its broken defined-benefit pension plans).

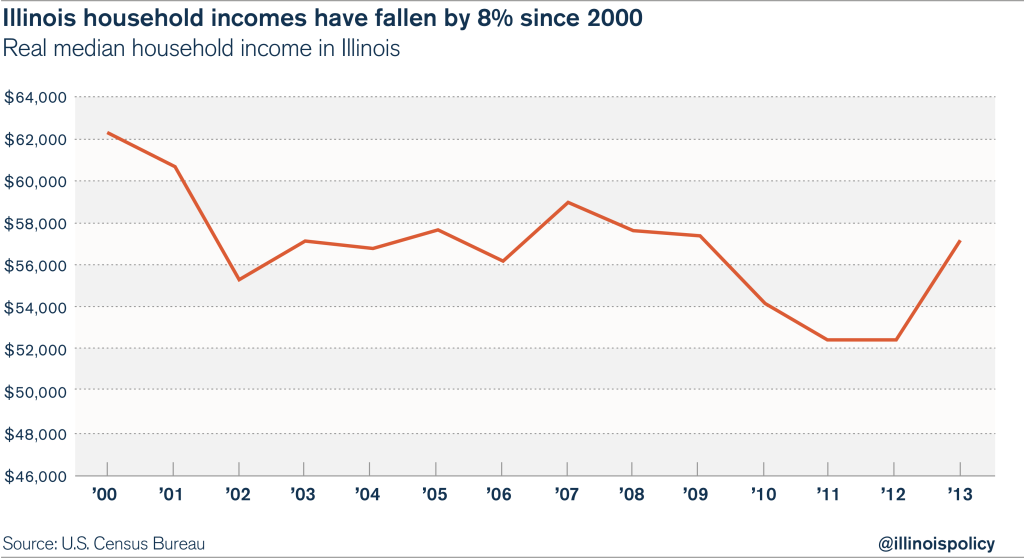

5. IMRF salaries climb, while Illinois household incomes stagnate

IMRF is demanding more and more from cities and their taxpayers at a time when it’s harder than ever for them to make these increased contributions.

Real median household incomes in Illinois have dropped since 2000 and have not yet recovered.

That means cities are struggling to collect revenue from families with less income, while increasing property taxes and cutting local services in order to meet IMRF’s demands for funding.

IMRF’s well-funded status does not make it the example for other pension plans in Illinois to follow. Its relative fiscal health is only due to the fact that it can force localities to fund it at the expense of those communities’ local vital services.

Cities will only end their fiscal crises when they are no longer subject to the instability of defined-benefit pension plans and these systems’ funding guarantees.

Some claim that the failures of Illinois’ multiple pension plans prove that Illinois pensions need funding guarantees and other controls. But simply throwing more and more revenue at broken pension systems won’t solve the problem. IMRF’s funding guarantee is evidence that forcing municipalities to pay for pensions above all else crowds out funds for core government services.

After all, pension systems are inherently political, opaque and void of accountability. As long as politicians maintain control over pensions, they’ll always find ways to exploit them and pass on the costs to taxpayers.

The real solution is to provide Illinois workers with a funding guarantee in the form of self-managed retirement plans, giving both taxpayers and localities more budget certainty and granting workers the retirement security they deserve.