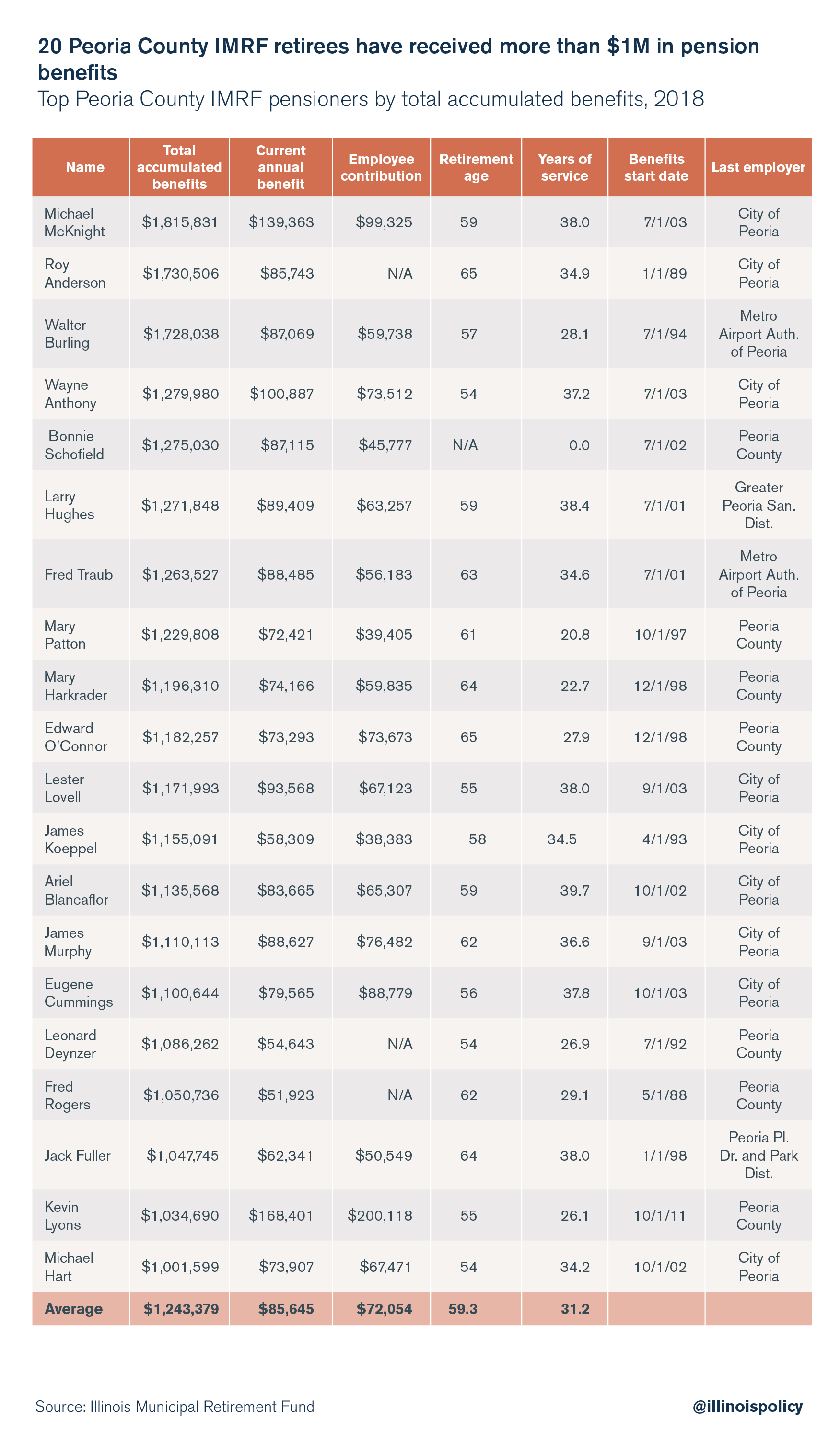

20 municipal retirees in Peoria County are pension millionaires

The average lifetime pension benefit among the county’s 20 highest-earning municipal retirees is more than $1.2 million, while their average total retirement contribution is less than $75,000.

When property tax bills hit Peoria County mailboxes in April, homeowners felt the weight on their shoulders grow heavier. Average effective property tax rates jumped to 2.7 percent from 2.4 percent over the year for county homeowners, according to property data company ATTOM Data Solutions, worsening a burden that already far exceeded the national average.

But that’s just one snapshot of long-running property tax growth that Peoria County residents have endured. Since 1996, residential property taxes have grown 86 percent faster than home values, an increase amounting to more than $700 per person.

What’s causing this long-term growth in property taxes? Rising pension costs are one significant factor. And a look at pension earnings for municipal retirees illustrates why those costs have brought about property tax hikes. Records from the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund, or IMRF, show 20 former local government employees having each collected between $1 million and $1.8 million since retiring. Among those retirees, three receive more than $100,000 annually in pension benefits.

The average lifetime pension benefit among the county’s 20 highest-earning municipal retirees is more than $1.2 million, while their average total retirement contribution is less than $75,000.

A plurality of the county’s pension millionaires worked for the city of Peoria. Pension payments for those former city employees contrast sharply with many of the residents they’ve served. The city’s median household income is around $46,500, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Those disparities come at a cost. As more tax dollars must be directed to government employees’ pension funds, fewer dollars are available to pay for core government services. For public safety pension funds across Peoria County, the fiscal crunch has already reached an extreme: Nearly 100 percent of every property tax dollar for the county’s municipal police and fire departments goes to pay for pensions, not services.

Local government pensioners themselves do not deserve blame for pension payments. State lawmakers wrote the rulebook by which benefits are calculated. And government worker retirements have been put at great risk due to overpromising.

Demographic challenges facing the county will only further challenge municipalities’ ability to grapple with rising pension costs. Among the 20 largest counties in Illinois, Peoria County has seen the heaviest net loss of residents to other counties in the U.S. in percentage terms, since 2010.

Ultimately, state lawmakers must find the political will to make changes to the Illinois Constitution that allow municipalities to bring pension costs to a level taxpayers can afford. Such changes would include allowing for revisions to future, not-yet-earned pension benefits, as well as instituting a check on government unions’ outsized power in collective bargaining negotiations.

In the meantime, the state should allow local governments to enroll all new employees in a stable, cost-effective 401(k)-style retirement plan. More than 20,000 state university employees have already opted for such a plan.

Property tax relief cannot be delivered to Peorians without structural changes to state and local pensions.